By Daniel Dunaief

Combative, loyal, determined, consequential, energetic and courageous. These are just a few of the many traits paleoanthropologists and others shared to describe the late Richard Leakey at the “Africa: The Human Cradle” memorial conference at Stony Brook University this week.

The founder of the Turkana Basin Institute in Kenya, Leakey, who partnered with SBU and received 34 grants from National Geographic over the course of his decades in science, was a part of nearly every presentation and discussion on the first day of the week-long event which closes tomorrow, June 9.

Held at the Charles B. Wang Center on the main campus, the conference brought together luminaries in the field who interlaced stories about their science in Africa with anecdotes — many of them humorous — about Leakey. Marilyn and Jim Simons, whose Simons Foundation announced last week that it was donating $500 million to the university, attended the entire slate of speakers on the first day.

Leakey was “one of the most important paleoanthropologists of our time,” Maurie McInnis, President of Stony Brook, said in opening remarks. His impact “can be felt across our campus and across the world.”

In an interview, former Stony Brook President Shirley Kenney, who helped bring Leakey to the university, suggested that he “put us into the elite of that whole research field.”

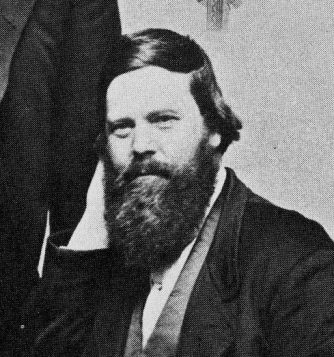

Leakey stubbornly entered his parents Mary and Louis’s chosen fields when he dropped out of high school, eager to make discoveries on his own and to contribute to his native Kenya.

In 1968, during a meeting at the National Geographic headquarters, Leakey “lobbied the committee to divert funding from his father’s money” to his own research, Jill Tiefenthaler, National Geographic CEO, said during her presentation.

‘Sitting on a knife edge’

Like Leakey, however, these scientists looked deep into the past to understand the lives of early humans, our distant ancestors and other organisms while looking for lessons that might help with the present and the future.

Dino Martins, Chief Executive Officer of the Turkana Basin Institute and Lecturer in the Department of Ecology & Evolutionary Biology, suggested that Leakey was driven by a sense of “childlike wonder” and a need to know “where we are, where we’re coming from and where we’re going.”

Leakey suggested that the extremely hot climate in Kenya was a potential model to understand how ancestral humans survived in hotter conditions, which are becoming increasingly prevalent amid global warming.

“There are many parallels in the past” in terms of extreme environments, Louise Leakey, director of public education and outreach for the Turkana Basin Institute and Richard and Meave Leakey’s daughter, said in an interview. “We’re sitting on this knife edge of really dramatic change now.”

In addition to encouraging science in Africa, Leakey also believed in engaging with students and researchers from a range of backgrounds and experiences. He wanted to ensure that people from every continent had an opportunity to join the ranks of scientists.

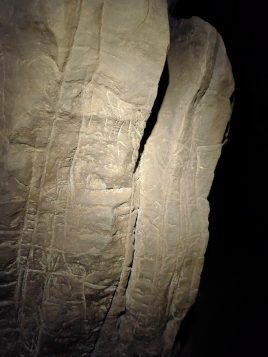

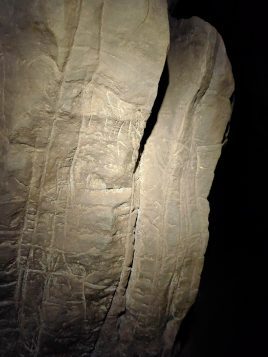

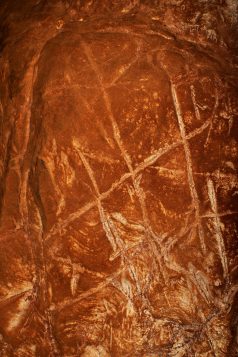

When presenting his research on Homo naledi, an extinct human with a brain a third the size of modern humans from South Africa who created burial sites and left behind etchings on a cave wall, Lee Berger, National Geographic Explorer in Residence, explained that he wished Leakey “had seen this and I think he would have been really angry with me.”

Words from a devoted daughter

In the final presentation of the first day, Louise Leakey shared memories of her upbringing and her father.

Among many pictures of her father and his discoveries over the years, Louise shared one in which she highlighted a pipe in the corner of the photo. She believed her father “rarely smoked it” but liked to pose with it in photos.

Louise Leakey recalled how one of her father’s partners, Kamoya Kimeu, proved a valuable partner in the search for fossils. When Kimeu died soon after Richard Leakey, Kimeu’s daughter Jennifer reached out to Louise to raise money for his funeral.

Louise Leakey has since learned that Jennifer never saw her father searching for fossils in the field. Rather, she learned all about his exploits when her mother read his letters each night to her before she went to bed.

A second generation of the two families is working together, as Jennifer has joined Louise in some of her fossil hunting work. The two daughters are also creating a comic strip, in many languages, that depicts the two of them hunting for fossils.

Leakey believes Jennifer Kimeu will serve as an inspiration to other Kenyans.

On the east side of Lake Turkana, Leakey and her team recently discovered the new head of a fossil. Before his death, her father said it was “time you found new skull.” Richard Leakey was right.

About LIMEHOF:

About LIMEHOF: