By Beverly C. Tyler

My neighbor, whose brother-in-law graduated from Setauket High School 73 years ago this month, gave me his copy of the “1951 Sachem,” the yearbook of that class — the last class to graduate from Setauket High School. There were just 12 in the class of ‘51, four girls and eight boys. The junior class of ‘51, set to graduate in ‘52 with 12 students, five girls and seven boys, would have to go elsewhere to complete their senior year, most likely to Port Jefferson.

The yearbook shows individual pictures of each member of the senior class and group pictures of sixth grade through the junior class. After pages dedicated to the graduating seniors, the booklet includes photos of the sports teams and seven other school activities, followed by advertisements from local businesses supporting the publication of the yearbook.

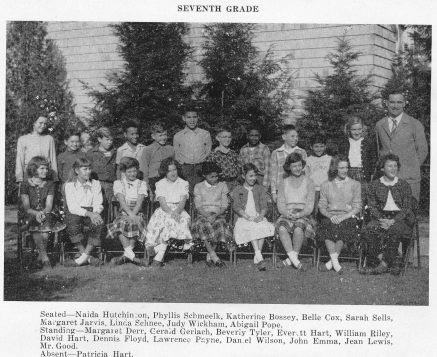

However, this isn’t a story about the class of ‘51 or ‘52. This is a story about my class, the seventh grade in 1951, destined to graduate in June 1953 from the new Setauket Junior High School. The picture shows 20 of 21 students, with only Patricia Hart absent. My class photo included

and our teacher, Mr. Good.

I don’t remember if Mr. Good taught the seventh grade the year before, but I believe he was gone the next year. In the 1951-52 school year, we spent most of the year at the old school, located on the south side of Route 25A, on the hill above where the stores, including the Village Chemist, are today. My class was on the second floor of the old wooden school building in the northeast corner room.

Mr. Good was a very no-nonsense teacher who had a humorous side that almost none of us appreciated. He told us, very proudly, that his foot was exactly twelve inches in length and intimated that if he had any troubles in the classroom, he could put his foot where it would do the most good. Mr. Good could also throw an eraser with pinpoint accuracy and did so with some frequency before the majority of students got to know him better.

One of the classmates I got along well with was Abigail Pope. She was a budding artist and loved to draw, which she often did during classes that didn’t interest her. Paying strict attention to the lesson at hand was absolutely necessary in Mr. Good’s classroom, and Abby had been presented with an eraser at least once before she was called to the front of the classroom.

I don’t know what she did that drew Mr. Good’s ire, but it could easily have been one of her very artistic nude drawings, which she often did. In front of the entire class, Mr. Good had Abby put out her right hand, palm up, and struck it with a ruler more than once. I remember that Abby never made a sound in response.

The best students in my class were Naida Hutchinson, Sarah Sells, Linda Schnee, and Everett Hart. Everett, who we called Bub, was also the best athlete. Margaret Jarvis was the cutest girl. All of this is, of course, subject to the passage of time and memory. Phyllis Schmeelk lived on a farm at the intersection of Bennett Road and North Country Road. What made it special for me were the horses in her side yard, right along the road. Katherine Bossey was a friend who often told me things I needed to hear. Her father ran a variety store in East Setauket. I once stole a baseball from the store, and Kathy set me straight. I always appreciated that from her.

John Emma’s father, Joe, was a barber. His shop was along East Setauket’s Main Street. I think at the time the family lived upstairs — I believe I got my first haircut there. My father took me, and when it was my turn, Mr. Emma put on a special seat that went across the arms of the barber chair to raise me to the proper level. It was a special day a few years later when I sat up in the chair as tall as I could and was told I didn’t need the booster chair anymore.

Larry Payne and I talked a lot about people in the community, and I remember Larry taking me down the hill from the old school to the small house just behind the stores at the corner of Main Street and Station Road — currently Gnarled Hollow Road. This was the home of Sarah Ann Sells. Mrs. Sells always offered us a peanut butter sandwich. She really seemed to enjoy being visited by kids from the school. When we moved to the new Setauket School and away from downtown East Setauket, some friendships seemed to change, and I don’t remember visiting Mrs. Sells or walking downtown at lunchtime or after school.

Jean Lewis lived on her family farm on Hub Road in South Setauket. The special feature of the area was Lewis’s Pond, where we would often ice skate in the winter, as it froze much earlier than the mill ponds in Setauket. Jean often invited some of her classmates to her home after skating, and I remember going as often as I could.

Jerry Gerlach was my best friend from the class, but the ones I hung out with most of the time after school and on weekends were all living on my street or close by, including Don Macauley, Paul Acker, Jackie Bennett, and Gene Cockshutt. We explored the woods around our houses, played stickball on Main Street at a time when few cars disturbed our games, rode our bikes all over the area, and spent a lot of time on and in the two mill ponds.

Moving to the new Setauket School was a pleasure for us. Everything was new and colorful and all on one floor. Each classroom had a door that opened directly to the outdoors. The students even helped by carrying books to the new library and classrooms. We were not just moving; we were helping. There were probably things we missed about the old school, but we said goodbye and embraced the new with enthusiasm.

Beverly Tyler is Three Village Historical Society historian and author of books available from the Three Village Historical Society, 93 North Country Rd., Setauket, NY 11733. Tel: 631-751-3730. http://WWW.TVHS.org