Curiosity and serendipity lead Kenyan woman to new life on Long Island

As a child in Kenya, Maureen Nabwire Manyasa-Zangrillo, now 35, loved learning about the world, but never dreamed she’d wind up living in the United States more than 7,000 miles away.

She lived several different lifestyles moving around Kenya as a child, she said, following her father’s developing career as an agricultural scientist to cities and villages and back again, fostering her love of new places and different kinds of people. As she grew up, so did that passion, expanding outward from her region and continent to encompass the entire world atlas she loved to study.

So when a serendipitous meeting over a charity project gave her a chance to travel to the other side of the world to make a new life on the North Shore of Long Island, she was ready. Now married to Joey Zangrillo, owner of Joey Z’s Restaurant in Port Jefferson, she is in the perfect setting to keep learning. “My love for geography and reading maps really helps when I meet people,” she said. “I have a clue about almost every corner of the globe.”

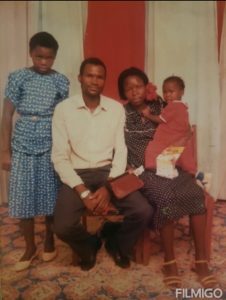

Growing up in Kenya

Before she even started primary school, Manyasa-Zangrillo had lived in Nakuru, the fourth largest urban area in the nation; her family’s village in Busia near the Ugandan border; a remote agricultural field station outside of Kenya’s capital Nairobi; and finally the thriving urban capital itself.

When it was time to start school, Manyasa-Zangrillo’s parents moved her and her younger sisters back to the quieter Busia, where they stayed with an aunt in a circular mud hut built in the traditional manner of their ethnic group, the Luhya tribe, while her father started the long process of coordinating construction of a modern brick house.

It was common in Kenya for breadwinners to work in the cities but keep their families back home in the villages, and such was the case for Manyasa-Zangrillo’s father. So building the house was slow progress over the next four or five years, with her father coordinating the work whenever he could make time to be home from Nairobi. Her mother, a primary school teacher, was gone awhile also to advance her training at teachers college.

Both parents made sure to stay connected to the girls. The father would send letters and packages to his daughters through the local bus company’s courier service, and — since landlines were rare — would schedule times to talk. Manyasa-Zangrillo remembered friends with landline telephones in their offices coming to tell the family what time to wait at the local payphone booth. She and her sisters would crowd around. “You’d find all of us at the booth — he’d talk to us turn by turn,” she said. “That’s how we found ways to connect.” Once the house was finished, the family finally had a landline of their own.

At age 10, Manyasa-Zangrillo’s lifestyle changed yet again, when she went to a Catholic boarding school, run by a very strict nun. “She was tough on us,” Manyasa-Zangrillo said, recalling that after parents visited, the staff would check the students to make sure they weren’t bringing in any outside food, drinks or treats.

Amid the rigid schedule and lack of comfort food, Manyasa-Zangrillo discovered bright spots: literature and geography. The curriculum included many storybooks, in both English and Swahili. For Manyasa-Zangrillo, reading was a beautiful escape. “It was a way of distracting myself from all the craziness and strictness that was going around,” she said.

Her beloved geography also gave her mind space to travel. “They would teach us about different areas — you learn about the geography, the weather of all these places, the planting, cultivation, commerce structures and all those things,” she said. “I was just curious about places.”

As she was growing up, she saw her parents rise in their education and careers. Her father obtained his university degree, a master’s and eventually a doctorate in plant breeding for arid and semi-arid regions, and her mother earned a bachelor’s in special education. “I’d see how strong willed they are,” the daughter said. “It was really motivating to see.”

This motivation helped Manyasa-Zangrillo succeed in her own education, earning a government scholarship to university herself. She struggled, though, to know what to study. In the end, she settled on law. “I wasn’t crazy about it,” she said, remembering she looked into other options like English linguistics, but her dad was even less crazy about that idea. “You have good grades — a top performance,” he told her, encouraging her to choose a major he saw as more serious.

After completing her education, she was admitted to the Kenyan bar and landed a job at the firm where she had carried out her required internship. She found ways to enjoy it. Serving documents or filing petitions, for example, took her all around the region. “I liked it because I love traveling, and I love seeing and exploring,” she said. “It was fulfilling my adventurous self because I’m going to new towns, new places.”

Charitable deeds

Another thing that helped fulfill her curiosity were opportunities to serve. Along with her sisters and other neighbors in Nairobi, where her family had relocated, Manyasa-Zangrillo had started a group called Youth for Change as a means to serve underprivileged children. So when her close friend from law school, Annette Kawira, invited her to volunteer at Bethsaida Community Foundation’s home for orphans, vulnerable children and children who had been living on the streets, she was happy to go along.

By 2016, Kawira had moved to the United States and found herself, of all places, in Joey Zangrillo’s Port Jefferson restaurant, then called Z Pita. Zangrillo had started a nonprofit organization and apparel company promoting racial reconciliation, and he was also donating 10% of his profits to charity. When Kawira saw a sign about the restaurant owner’s philanthropy, she remembered the Bethsaida orphanage and made a fast friendship and partnership with Zangrillo.

As the two organized fundraising on Long Island, Manyasa-Zangrillo served as the woman on the ground in Kenya, liaising between them and the children’s home. Logistical texts and FaceTime interactions between her and Zangrillo blossomed into friendship — she enjoyed his sense of humor — then took on a flirtatious air. Interest sparked.

By the time he planned to take a trip to Kenya to visit Bethsaida and meet the children in 2017, he was also looking forward to meeting her. She remembered being nervous about what he would be like in person, but after she opened her door to him, she said, “he just busted in with so much energy, and I was like, OK, we’re going to get along.”

For his part, Zangrillo was drawn to her compassion. “What made me fall in love with my wife is when I saw the love in her eyes for the children in the orphanage,” he said. “That second, I knew.”

To Long Island and marriage

The trip was a success and plans to install a well at the orphanage moved forward, as did plans for Manyasa-Zangrillo to visit Long Island, which she did that fall. Joey Zangrillo sent Kawira and another Kenyan friend in a limo to pick her up from the airport, and she was charmed. Manhattan charmed her, too — it was larger than life, just like the movies. She even sat in the audience at “The Daily Show” to see the comic Trevor Noah she’d watched back in Africa.

Manyasa-Zangrillo found the Port Jefferson community and Zangrillo’s friends welcoming and warm, but the weather less so. “The drastic hot to cold — I felt like my ears were going to fall off,” she said.

The weather wasn’t enough to keep her away. After a couple months back in the more temperate climate of Kenya, she kept thinking about New York, Zangrillo and the possibilities. “In my legal profession, I was wallowing a bit,” she said. “Am I going to do this for the rest of my life, yet I’m feeling like this is not what I really wanted to do.”

So she took a risk and came back in early 2018, still unsure what the future would hold. Zangrillo was more certain. “He was like, ‘You know what? I would like you to stay.’”

They married that summer. “There’s no need to overthink something that is good,” she said of the quick timeline, adding that where immigration law is involved, “you date through the marriage because you don’t have a long courtship.”

She found her transition to New York easy, partly because of Kawira and other Kenyan connections, but also because of her new husband. He’d told so many people about her and about the orphanage that restaurantgoers and friends were thrilled to meet her, and to learn more about her. “It’s so refreshing because when I walk in, people say, ‘You must be Maureen,’” she said. “Through the restaurant, I’m meeting people every day.”

For Zangrillo, having her in town is “a godsend,” he said. “It changed my life — I’m a happy man, with a happy life.”

Careerwise, the future is still open for Manyasa-Zangrillo. She has taken a paralegal class and is studying the American legal system in case she wants to return to her original career path. She helps at the restaurant and has introduced a top-selling menu item — the lemon potatoes. The couple are continuing their charity work, as well, with hopes to install a school library for students in a Nairobi slum settlement.

Now living in Setauket, Manyasa-Zangrillo has come to appreciate the North Shore’s feel and location, not too close and not too far from the city. “My life dream when I was younger was just to be somewhere that is full of nature and very serene, and the environment is cool,” she said. “I’d say I got it here.”