By Beverly C. Tyler

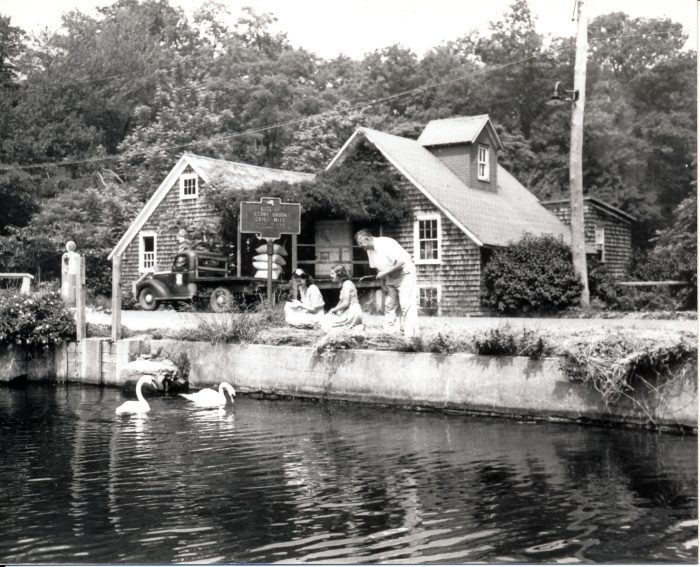

A fine example of the many Colonial farmhouses in the Three Village area is the two-and-a-half story farmhouse on Main Street in Stony Brook, just west of the mill pond, at the corner of Hawkins Road. This attractive white farmhouse with its nine-over-six small-pane windows was built about 1750.

The earliest known resident of this farmhouse was Joseph Smith Hawkins, son of George and Ruth Hawkins. He was born in Stony Brook on February 7, 1763. Like his father, Joseph was a farmer. He married Phebe Williamson and they had two sons, Nathaniel – born 1791 – and Joseph Smith – born 1796.

Sometime after 1810, Joseph Smith Hawkins built the house diagonally across the street. When their father died in 1827, the brothers traded houses. Joseph moved across the road to the original family farmhouse and Nathaniel moved into his brother’s house. Nathaniel was a wheelwright and operated a shop near his home.

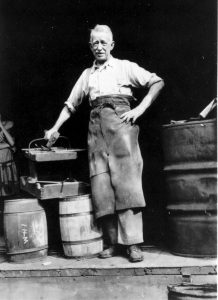

Joseph was a farmer his entire life and his son Joseph Smith Hawkins – born 1827 – continued to live in the farmhouse. Joseph married Henrietta Sophia Davis on February 10, 1858 and together they farmed the land until the early 20th century. Henrietta died June 6, 1907 and Joseph died April 12, 1911. The farm, until about 1950, included a number of barns and related outbuildings.

Joseph Hawkins’ grandson Percy Smith, born 1892, and a Stony Brook resident his entire life, remembered, in an interview in 1976, when his grandfather ran the 65-acre farm. “He used to raise wheat and rye and corn, no small vegetables except in the family garden. There was a big barn on the south side of the house, a hog pen and many other buildings which are all gone now. There was, as I remember, six horses and ten to twelve cows. I used to, when I was a boy, drive the cows to pasture each morning and back in the evening. The pasture was more than a mile away and I got 75 cents a week.”

“He used to make butter and take it to the store and trade it in and get groceries. Farming used to be a mainstay of the village, plus the boats that used to bring things in and take things out. My grandfather used to cut and ship cordwood to New York City. The dock at Stony Brook used to be covered with hundreds of cords of wood.”

Percy also remembered how Stony Brook families relied on each other for many of their necessities of life. The farmers supplied the food products and the ship captains supplied transportation for the goods that were sold in New York City and Connecticut. The coastal schooners also brought to Stony Brook many items that were not grown or manufactured here. The merchants then bought and sold from both the farmers and the schooner captains.

The 19th century brought many changes that affected the close interdependent relationship of the farmers, ship captains, and merchants. The opening of the Erie Canal in 1826 brought coal for fuel from Pennsylvania and other states and hastened the decline of the use of cord wood for fuel in New York City.

Wheat and other grains from the midwest, first from Ohio, were shipped on the Erie Canal and began arriving in New York City in large quantities. Most of the local grist mills found it difficult, if not impossible, to match the low price of midwest grains and either adapted or went out of business. Percy Smith also noticed these changes.

“The older people died off and the younger ones didn’t want to bother with farming because they could make more money doing something else. They didn’t want the drudgery that their fathers had so the farms were sold off.”

Thus ended most of the small individual farms in the Three Village area. The local farmer was always a hardworking individual who took a great deal of pride in his work. Most of the farmers continued to work their farms as long as they were able and, in the decades leading up to the 20th century, they usually passed the farm on to their sons and grandsons.

The farms are gone, but many of the farmhouses remain as witnesses to a lifestyle that has passed on. With a bit of imagination you can stand in front of these homes and visualize what it was like to be a part of that era.

Beverly Tyler is Three Village Historical Society historian and author of books available from the Three Village Historical Society, 93 North Country Rd., Setauket, NY 11733. Tel: 631-751-3730.