By Daniel Dunaief

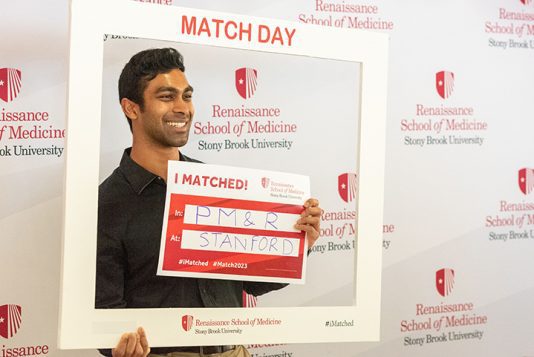

On May 14, the Renaissance School of Medicine celebrated 50 years since its first graduating class, as 125 students entered the ranks of medical doctor.

The newly minted doctors completed an unusual journey that began in the midst of Covid-19 and concluded with a commencement address delivered by former National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Dr. Anthony Fauci.

Dr. Fauci currently serves as Distinguished University Professor at the Georgetown University School of Medicine and the McCourt School of Public Policy and also serves as Distinguished Senior Scholar at the O’Neill Institute for National and Global Health Law.

“I have been fortunate to have had the privilege of delivering several commencement addresses over the years,” Dr. Fauci began. “Invariably, I have included in those addresses a reference to the fact that I was in your shoes many years ago when I graduated from medical school.”

This graduating class, however, has gone through a journey that “has been exceptional and, in some cases unprecedented,” Dr. Fauci added.

Indeed, the Class of 2024 started classes remotely, learning a wide range of course online, including anatomy.

“Imagine taking anatomy online?” Dr. Bill Wertheim, interim Executive Vice President for Stony Brook Medicine, said in an interview. “Imagine how challenging that is.”

Dr. Wertheim was pleased with the willingness, perseverance and determination of the class to make whatever contribution they could in responding to the pandemic.

The members of this class “were incredibly engaged. They rolled up their sleeves and pitched in wherever they could to help the hospital manage the patients they were taking care of,” said Wertheim, which included putting together plastic gowns when the school struggled to find supplies and staffing respite areas.

“Hats off to them” for their continued zeal and enthusiasm learning amid such challenges, including social issues that roiled the country during their medical training, Wertheim said.

Student experience

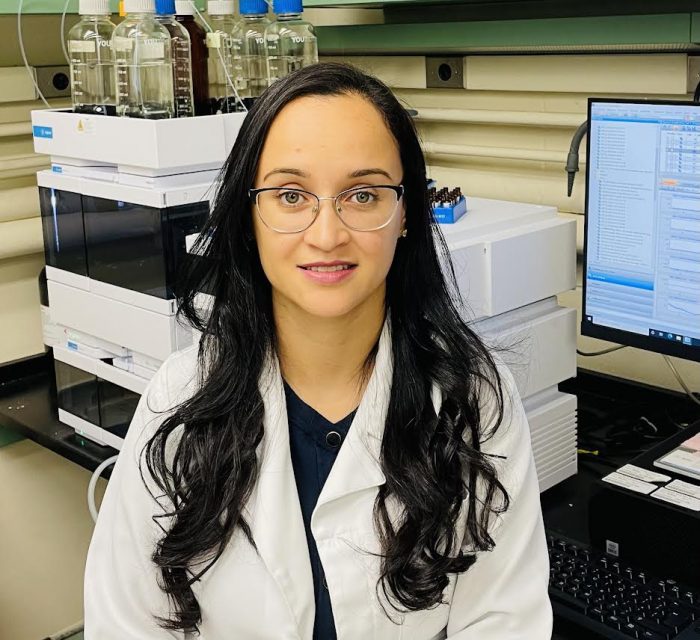

For Maame Yaa Brako, who was born in Ghana and moved to Ontario, Canada when she was 11, the beginning of medical school online was both a blessing and a curse.

Starting her medical education remotely meant she could spend time with the support system of her family, which she found reassuring.

At the same time, however, she felt removed from the medical community at the Renaissance School of Medicine, which would become her home once the school was able to lift some restrictions.

For Brako, Covid provided a “salient reminder” of why she was studying to become a doctor, helping people with challenges to their health. “It was a constant reminder of why this field is so important.”

Brako appreciated her supportive classmates, who provided helpful links with studying and answered questions.

Despite the unusual beginning, Brako feels like she is “super close” to her fellow graduates.

Brako was thrilled that Dr. Fauci gave the commencement address, as she recalled how CNN was on all the time during the pandemic and he became a “staple in our household.”

Brako will continue her medical training with a residency at Mass General and Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, where she will enter a residency in obstetrics and gynecology.

Mahesh Tiwari, meanwhile, already had his feet under him when medical school started four years ago. Tiwari, who is going to be a resident in internal medicine at Robert Wood Johnson Hospital in New Brunswick, New Jersey, earned his bachelor’s degree at Stony Brook.

He was able to facilitate the transition to Long Island for his classmates, passing along his “love for the area,” recognizing the hidden gems culturally, musically and artistically, he said.

After eight years at Stony Brook, Tiwari suggested he would miss a combination of a world-class research institution with an unparalleled biomedical education. He also enjoyed the easy access to nature and seascapes.

A look back

Until 1980, Stony Brook didn’t have a hospital, which meant that the medical students had to travel throughout the area to gain clinical experience.

“Students were intrepid, traveling all across Long Island, deep into Nassau County, Queens and New York City,” said Wertheim.

In those first years, students learned the craft of medicine in trailers, as they awaited the construction of buildings.

Several graduates of Stony Brook from decades ago who currently practice medicine on Long Island shared their thoughts and perspective on this landmark graduation.

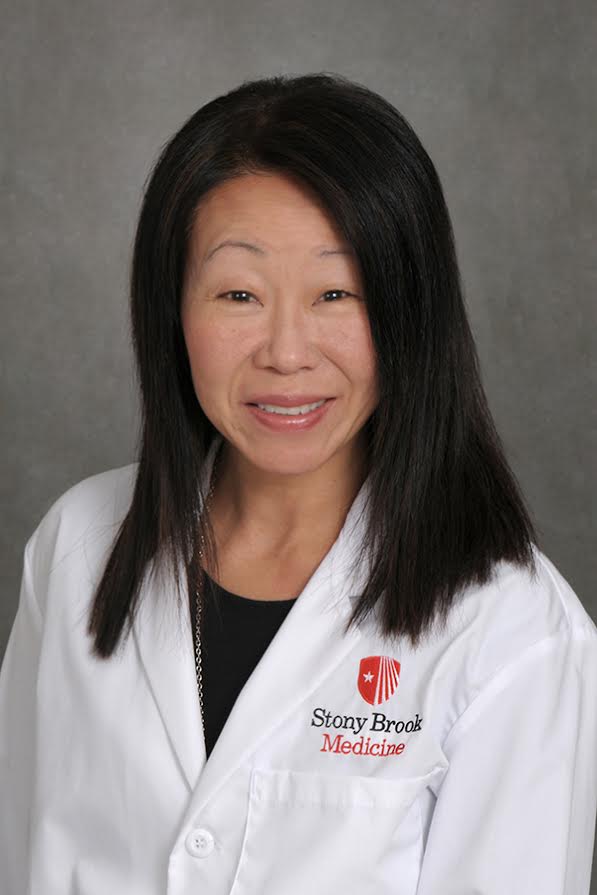

Dr. Sharon Nachman, Chief of the Division of Pediatric Infectious Diseases at Stony Brook Children’s Hospital, graduated from Stony Brook Medical School in 1983.

In the early years, the students were an “eclectic group who were somewhat different than the typical medical school students,” which is not the case now, Nachman said.

When Nachman joined the faculty at Stony Brook, the medical school didn’t have a division of pediatric infectious diseases. Now, the group has four full time faculty with nurse practitioners.

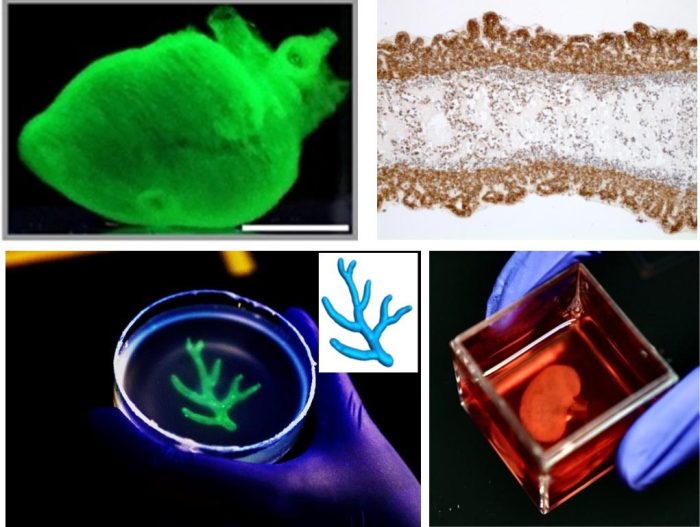

The medical school, which was renamed the Renaissance School of Medicine in 2018 after more than 100 families at Renaissance Technologies made significant donations, recognizes that research is “part of our mission statement.”

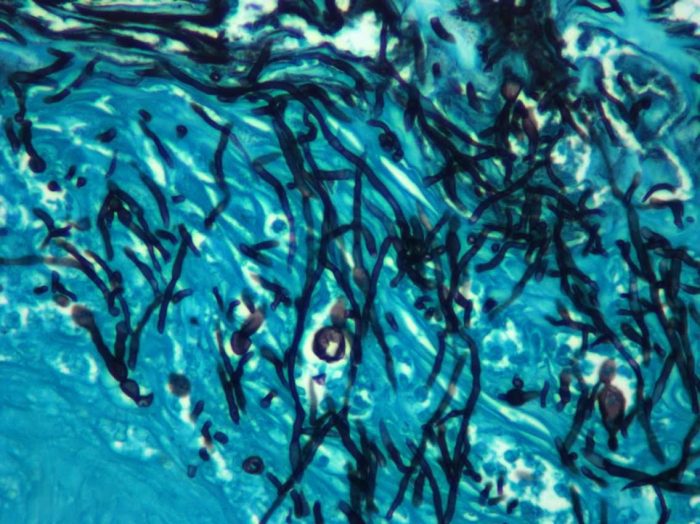

Stony Brook played an important role in a number of medical advances, including Dr. Jorge Benach’s discovery of the organism that causes Lyme Disease.

Stony Brook is “not just a medical school, it’s part of the university setting,” added Nachman. “It’s a hospital, it has multiple specialties, it’s an academic center and it’s here to stay. We’re not just the new kids on the block.”

Departments like interventional radiology, which didn’t exist in the past, are now a staple of medical education.

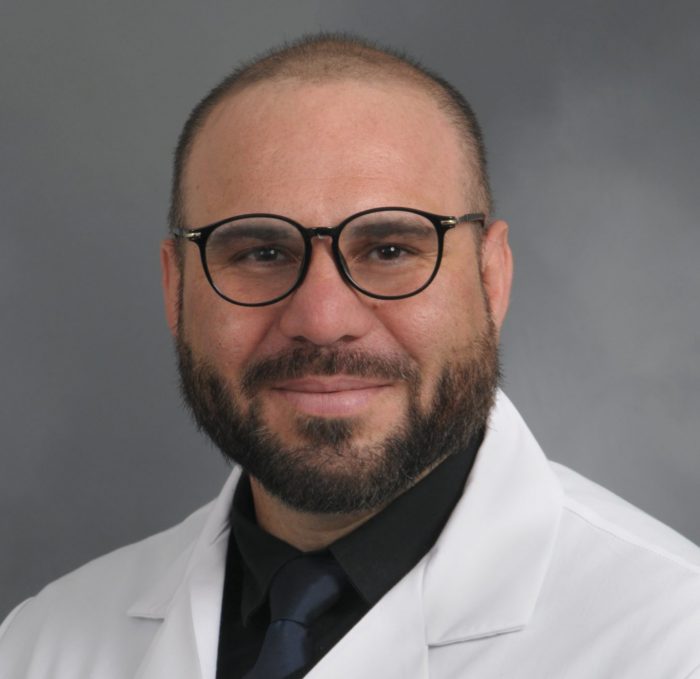

Dr. David Silberhartz, a psychiatrist in Setauket who graduated in 1980, appreciated the “extraordinary experience” of attending medical school with a range of people from different backgrounds and experiences. He counts three of the members of his class, whom he met his first day, as his best friends.

Silberhartz, who planned to attend commencement activities, described the landmark graduation as a “wonderful celebration.”

Aldustus Jordan III spent 43 years at the medical school, retiring as Associate Dean for Student Affairs in January 2019.

While he had the word “dean” in his title, Jordan suggested that his job was to be a “dad” to medical students, offering them an opportunity to share their thoughts, concerns and challenges.

As the school grew from a low of 18 students to a high of 150 in 2021, Jordan focused on keeping the small town flavor, so students didn’t become numbers.

“I wanted to make sure we kept that homey feeling, despite our growth,” said Jordan.

Jordan suggested that all medical schools recognize the need for doctors not only knowing their craft, but also having the extra touch in human contact.

“We put our money where our mouth is,” Jordan said. “We put a whole curriculum around that” which makes a difference in terms of patient outcomes.

Jordan urged future candidates to any medical school, including Stony Brook, to speak with people about their experiences and to use interviews as a chance to speak candidly with faculty.

“When you have down time, you have to enjoy the environment, you have to enjoy where you live,” Jordan said.

As for his own choice of doctors, Jordan has such confidence in the education students receive at Stony Brook that he’s not only a former dean, but he’s also a patient.

His primary care physician is a SBU alumni, as is his ophthalmologist.

“If I can’t trust the product, who can?” Jordan asked.

As for Fauci, in addition to encouraging doctors to listen and be prepared to use data to make informed decisions, he also suggested that students find ways to cultivate a positive work life balance.

“Many of you will be in serious and important positions relatively soon,” Fauci said. “There are so many other things to live for and be happy about. Reach for them and relish the joy.”