By Daniel Dunaief

When Minghao Qiu woke up in Beijing on Jan. 12, 2013 during his freshman year in college, he couldn’t believe what he was seeing or, more appropriately, not seeing. The worst air pollution day in the history of the city mostly blocked out the sun, making it appear to be closer to 8 p.m. than a typical morning.

While Qiu’s life path includes numerous contributing factors, that unusual day altered by air pollution had a significant influence on his career.

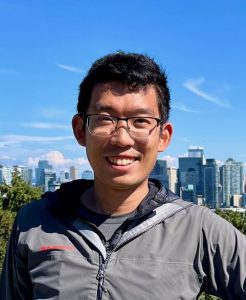

An Assistant Professor at Stony Brook University, Qiu straddles two departments that encapsulate his scientific and public policy interests. A recent hire who started this fall, Qiu will divide his time equally between the School of Marine and Atmospheric Sciences and the Renaissance School of Medicine’s Program in Public Health.

Qiu studies fundamental questions in atmospheric sciences as they influence human health.

He is part of several new hires who could contribute to the climate solutions center that Stony Brook is building on Governors Island and who could provide research that informs future policy decisions.

Noelle Eckley Selin, who was Qiu’s PhD advisor at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and is Professor in the Institute for Data, Systems and Society and the Department of Earth, Atmospheric and Planetary Sciences, suggested Qiu is a valuable scientific, policy and educational asset.

“Stony Brook is doing a lot to address climate in a serious way with great research,” Selin said. Qiu joining the institution “could really help out the university’s broader climate efforts and make them more impactful.”

Selin appreciated how Qiu was eager to dive deeper into questions, wanting to ensure that conclusions were valid and asking how to use data to test various ideas.

As a mentor, Qiu has proven inspirational.

“A lot of my current students will go and talk to him and come back to me and say, ‘[Qiu] had five excellent ideas on my project,’” Selin said. “That’s characteristic of how he works. He’s really generous with his time and is always thinking about how to look at problems.”

Policy focus

Using causal inference, machine learning, atmospheric chemistry modeling, and remote sensing, Qiu focuses on environmental and energy policies with a global focus on issues involving air pollution, climate change and energy transitions.

Qiu would like to address how climate change is influencing the air people breathe. Increasing heat waves and droughts cause people to use more energy, often through air conditioning. The energy for the electricity to power temperature controls comes from natural gas, coal, or fossil fuels, which creates a feedback loop that further increases pollution and greenhouse gases.

“Our work tries to quantify this,” Qiu said.

He also analyzes the impact of climate change on wildfires, which affects air quality.

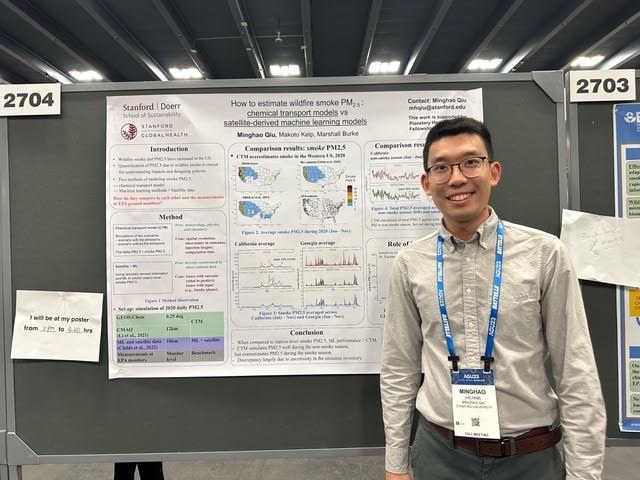

In a research paper published last year, Qiu joined several other scientists to analyze the impact of wildfires on air quality.

The study, published in the journal Nature, found that since at least 2016, wildfire smoke eroded about a quarter of previous decades-long efforts to reduce the concentration of particulates above 2.5 microgram in several states.

Wildfire-driven increases in ambient particulates are unregulated under air pollution laws.

The authors showed that the contribution of wildfires to regional and national air quality trends is likely to grow amid a warming climate.

In his research, Qiu seeks to understand how to use energy and climate policy to address air pollution and greenhouse gases.

“Renewable energy and climate policy in general provides potential benefits,” Qiu said.

He uses publicly available data in his models.

New York pivot

While wildfires have been, and likely will continue to be, an area of focus for his work, Qiu plans to shift his focus to the kind of pollution that is typically more prevalent in New York.

In large urban cities, pollution often comes from a concentration of traffic, as people commute to and from work and drive to the city for entertainment and cultural events.

“We are going to pivot a little bit, especially to factors that are more relevant” to the Empire State, he said.

While climate change is a broad category that affects patterns across the world, air pollution and its impacts are more regional.

“The biggest impact of air pollution happens locally” particularly in terms of health effects, Qiu said.

From Beijing to MIT

Born and raised in Beijing, Qiu began connecting how climate or energy policy influences air pollution at MIT.

“When I started my PhD, there was not much real world data analysis” that linked how much renewable energy helps air quality, Qiu said. “We have historical data to do that, but it’s a lot more complex.”

After he graduated from MIT, Qiu moved to Stanford, where he shifted his focus to climate change.

“There, I got to collaborate more directly with people in the public health domain,” he said, as he focused on wildfires.

Personal choices

Despite studying air pollution and climate change, Qiu does not have HEPA filters in every room and, by his own admission, does not live a particularly green life. He does not have an electric car, although he plans to get one when he needs a new vehicle. He urges people not to sacrifice the living standards to which they are accustomed, which can include eating their preferred foods and traveling to distant points in the world.

Qiu believes there are choices individuals can make to help, but that the kind of decisions necessary to improve the outlook for climate change come from centralized government policy or large enterprises.

“I have great respect for people who change their personal behavior” but he recognizes that “this is not for everyone.”

A resident of Hicksville, Qiu lives with his wife Mingyu Song, who is a software engineer. The couple met when they were in high school.

When he’s not working on climate models, he enjoys playing basketball and, at just under six feet tall, typically plays shooting guard.

As for his research, Qiu does “rigorous scientific research” that draws from historical data.

“I feel a sense of urgency that we would like to get the answers to many of the scientific evidence as quickly as possible to communicate to policy makers,” he said.

He wants his research to be impactful and to help policy makers take “appropriate measures.”

He’s heard numerous stories from a day in which the comfortable, clear air provided an incongruous backdrop for the mass murders. He has heard about people who were blown out of the buiding amid a combustible blast and about how difficult it is to put out a cesium fire.

He’s heard numerous stories from a day in which the comfortable, clear air provided an incongruous backdrop for the mass murders. He has heard about people who were blown out of the buiding amid a combustible blast and about how difficult it is to put out a cesium fire.