By Daniel Dunaief

When they can’t stand the heat, bay scallops can’t get out of the proverbial kitchen.

A key commercial shellfish with landings data putting them in the top five fisheries in New York, particularly in the Peconic Bay, bay scallops populations have declined precipitously during a combination of warmer waters and low oxygen.

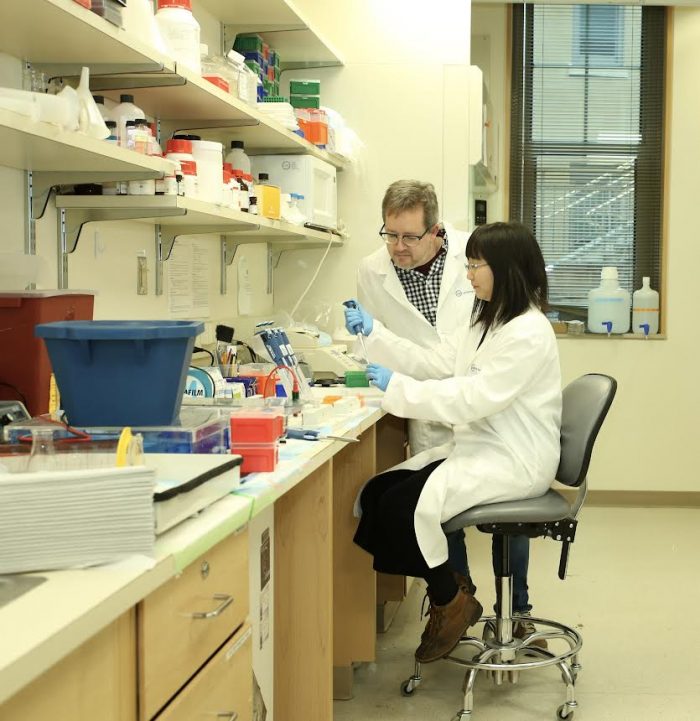

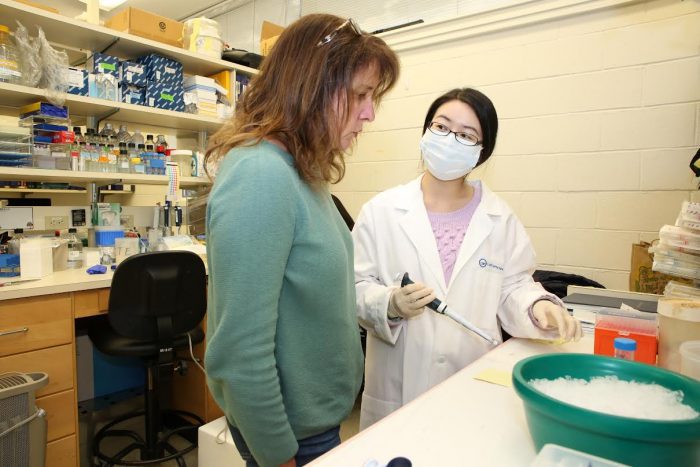

In a study published in the journal Global Change Biology, Christopher Gobler, Stony Brook University Endowed Chair of Coastal Ecology and Conservation and Stephen Tomasetti, a former Stony Brook graduate student, along with several other researchers, showed through lab and field experiments as well as remote sensing and long-term monitoring data analysis how these environmental changes threaten the survival of bay scallops.

Bay scallops are “quite sensitive to different stressors in the environment,” said Tomasetti, who completed his PhD last spring and is currently Visiting Assistant Professor of Environmental Studies at Hamilton College in Clinton, New York. Of the regional shellfish, bay scallops are the most sensitive to environmental stress.

Indeed, since 2019, bay scallops have declined by between 95 and 99 percent amid overall warming temperatures and extended heat waves. These declines have led to the declaration of a federal fishery disaster in the Empire State.

Tomasetti used satellite data to characterize daily summer temperatures from 2003 to 2020, which showed significant warming across most of the bay scallop range from New York to Cape Cod, Massachusetts. He monitored four sites with sensors in the water in addition to satellite data during a field deployment with scallops.

At the warmest site, which was in Flanders Bay, New York, the temperature was above the 90th percentile of its long term average during an eight-day period that overlapped with the scallop deployment. The bay scallops in Flanders Bay were “all dead by the end of the heat wave event,” Tomasetti said.

At the same time, low levels of oxygen hurt the bay scallops which, like numerous other shellfish, feed on phytoplankton. Oxygen levels are declining in some of these bays as nitrogen from fertilizers and septic systems enter these waterways. High nitrogen levels encourage the growth of algae. When the algae die, they decay, which uses up oxygen and releases carbon dioxide into the water.

Field and lab studies

In the field, Tomasetti measured the heartbeat of bay scallops in East Harbor, Massachusetts by putting optical infrared sensors on them that took heartbeat readings every 15 minutes for a month.

When the average daily temperature increased, their average heart rate climbed, which the scientists used as a proxy for their respiration rate. A higher respiration rate meant that the scallop was expending energy more rapidly, potentially leading to reductions of energy reserves.

Additionally, Tomasetti measured how quickly the scallops fed on algae in the lab under warm temperatures and low oxygen. These conditions caused the scallops to stop feeding or to feed slowly. Tomasetti interpreted this as a sign that they were waiting out the stress.

In the lab, bay scallops in the same conditions as the bays from Long Island to Massachusetts had the same reactions.

While a collection of fish and invertebrates feed on bay scallops, the effect of their die off on the food web wasn’t likely severe.

“I think there are other prey items that are likely redundant with scallops that cushion the impact,” Gobler explained in an email.

Solutions

As for solutions, global warming, while an important effort for countries across the planet, requires coordination, cooperation and compliance to reduce greenhouse gases and lower the world’s carbon footprint.

On a more local and immediate scale, people on Long Island can help with the health of the local ecosystem and the shellfish population by reducing and controlling the chemicals that run off into local waters.

Waste management practices that limit nutrients are “super helpful,” Tomasetti said. “Supporting restoration (like the clam sanctuaries across Long Island that are increasing the filtration capacities of bays) is good.”

Gobler is encouraged by county, state and federal official responses to problems such as the decline in bay scallops, including the declaration of a federal disaster.

Long Island experience

A graduate student at Stony Brook for five years, Tomasetti was pleasantly surprised with the environment.

He had lived in New York City, where he taught high school biology for five years, before starting his PhD.

His perception was that Long Island was “a giant suburb” of New York. That perspective changed when he moved to Riverhead and enjoyed the pine forest, among other natural resources.

He and his wife Kate Rubenstein, whom he met while teaching, enjoyed sitting in their backyard and watching wild turkeys walking through their property, while deer grazed on their plant life.

Initially interested in literature at the University of Central Florida, Tomasetti took a biology course that was a prerequisite for another class he wanted to take. After completing these two biology classes, he changed his college and career plans.

Teaching high school brought him into contact with researchers, where he saw science in action and decided to contribute to the field.

At Hamilton College, Tomasetti has started teaching and is putting together his research plan, which will likely involve examining trends in water quality and temperature. He will move to the University of Maryland Eastern Shore in Princess Anne, MD this fall, where he will be an assistant professor in coastal environmental science.

As for his work with bay scallops and other shellfish on Long Island, Tomasetti looked at the dynamics of coastal systems and impacts of extreme events on economically important shellfish in the area.

Tomasetti is not just a scientist; he is also a consumer of shellfish. His favorite is sea scallops, which he eats a host of ways, although he’s particularly fond of the pan seared option.