By Sabrina Artusa

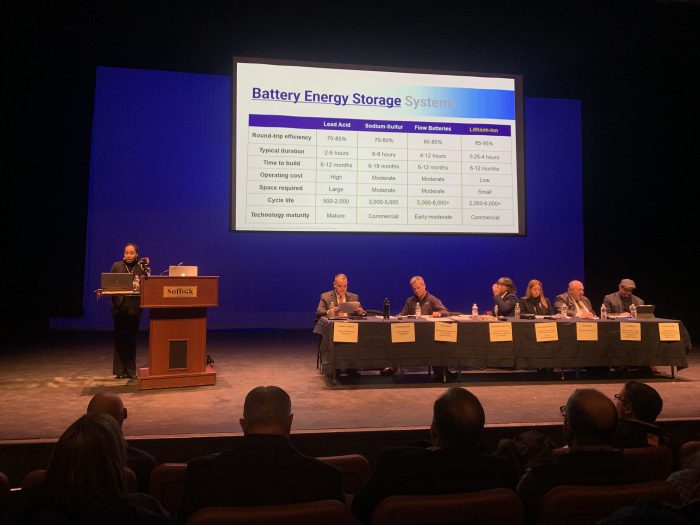

Town of Brookhaven Supervisor Dan Panico (R) held a community forum to discuss battery energy storage systems on Tuesday, Jan 21 at Suffolk County Community College in Selden.

The forum featured a panel of professionals including an energy storage safety specialist, a deputy town attorney, a Stony Brook University professor and a chief fire marshal.

Two battery energy storage facilities are proposed in Setauket by the Shell Group company Savion Energy. One facility is already being built in Patchogue.

The batteries

The forum began with a presentation by Camille Warner, project manager of a clean energy siting team for the New York State Energy Research and Development Authority.

Lithium-ion batteries are intended to hold energy, thus increasing the resilience of the grid by “provisioning essential resources” such as solar or wind energy. When renewable energy isn’t available, like when it is cloudy or windless, the batteries would release the energy stored, therefore prolonging the amount of energy we are able to derive from renewable resources.

Lithium-ion batteries “store the most energy per unit weight or volume of any other battery system,” Warner said. To add, the batteries can help supplement energy during peak hours or when grid prices are high.

One system is proposed for a lot off Sheep Pasture Road and another is proposed between Parsonage and Old Town roads.

Moss landing fires

A 350-kilowatt facility in Moss Landing, California. started a fire on Jan. 16. It was extinguished by Monday, Jan. 20. The cause of the fire is unknown, but it necessitated the evacuation of residents.

“At Moss Landing there was just open racks in an open building which had no fire breaks in between. We also know that the system was designed in 2017…The codes were not mature…the codes have gotten so much more mature,” Paul Rogers, an energy storage specialist for Energy Safety Response Group and a former New York City Fire Department Lieutenant, said.

He also mentioned that the Moss Landing BESS did not go through any large-scale fire testing. It is a current standard to test the failure of a BESS.

The BESS systems proposed in Setauket will not be operated in a designated-use building, so the scale of any possible fire would not reach the level of the one in Moss Landing. The Brookhaven systems are compartmentalized.

While residents were evacuated during the fire, testing has not revealed dangerous levels of hydrogen chloride, hydrogen fluoride, particulates or carbon monoxide.

Chief Fire Marshal Christopher Mehrman said that it is doubtful an evacuation would be needed if the Brookhaven systems were to ever catch fire as it isn’t likely the fire would ever escape the property.

When Panico asked what radius from a fire would experience diminished, and potentially harmful air quality, Mehrman said: “There is no defined radius. There are many factors that play into it – wind, time of day … whether there is a weather inversion that is keeping [the gasses] close to the ground or it is just flying up and going away.”

Safety measures

The Energy Safety Response Group has worked with the state to refine the code.

Precautions include a specific plan in case of failure. Experts must be present within four hours of a fire to help the fire department and should be available over the phone immediately.

“Someone who will take responsibility and start the decommissioning process should a fire take place … so the fire department can be relieved,” said Rogers.

Rogers also said that in addition to the National Fired Protection Agency’s compressed gasses and cryogenic fluids code, the state plans to add extra mandatory safety measures in preparing for and preventing BESS fires.

Annual training will be provided to fire departments, annual inspections of the systems will take place, and the BESS will be peer reviewed by a third party before and after being built, paid for by the developing company. “This is not in NFPA 55. We went above and beyond the gold standard as far as I am concerned,” Rogers said.

Rogers also said his group provides thorough, site-specific training to fire departments. In the case of a fire, the fire department is advised to let the module burn itself out and to use water to prevent the spread to other racks.

“Limit the spread of the fire. That is the whole goal of this … we want to keep it within the box,” Rogers said.

Explosions caused by thermal runaway are unlikely, according to Mehrman, who said, “Vapors burn off rather than lead to an explosion. We have not seen any battery storage facility fire that has failed beyond the perimeter.”

Other concerns

Deputy Town Attorney Beth Reilly addressed legal questions as they pertained to the town code.

In accordance with the town code, which dictates that noise levels cannot exceed 65 decibels at the property line from 7 a.m. to 10 p.m. or 50 decibels after 10 p.m., the site will include buffers and vegetation to limit noise.

Panico, in response to financial queries, said the company “will pay taxes in accord with any other development” and “this is in no way being done with anything related to the landfill.”

Both Setauket sites are zoned appropriately, so the systems are permitted in those areas, despite their proximity to residential areas.

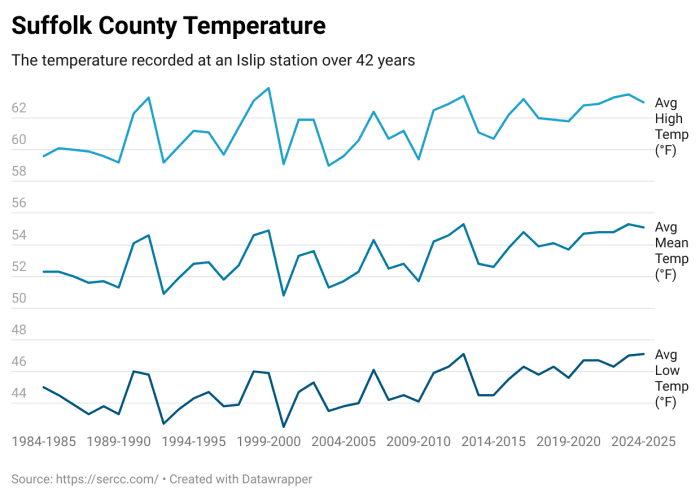

Panico acknowledged the relevance of battery energy storage systems by appreciating the benefits of renewable energy in the fight against climate change. “There is a value from harnessing power from the wind and the sun,” he said.

Councilmembers Jonathon Kornreich (D-Stony Brook), Neil Manzella (R-Selden), and Neil Foley (R-Patchogue) were also among those in attendance.