By Daniel Dunaief

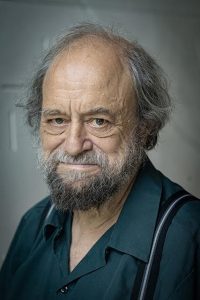

Stony Brook University might need to rename a wing of the C.N. Yang Institute for Theoretical Physics the Breakthrough Prize alley. That’s because theoretical physicist Alexander Zamolodchikov recently shared a $3 million prize in fundamental physics, matching a similar honor his neighbor on the floor and in the department, Peter van Nieuwenhuizen, earned in 2019.

Zamolodchikov shared this year’s award with University of Oxford Professor John Cardy for their contributions to quantum field theories which describe particle physics as well as magnetism, superconducting materials and the information content of black holes.

“I’m not working for prizes, but it’s kind of encouraging that other people think that my contribution is significant,” said the Russian-born Zamolodchikov, who joined Stony Brook in 2016 and had previously worked at Rutgers for 26 years, where he co-founded the High Energy Theory Center.

While Zamolodchikov was pleased to win the award and was understated in his response, his colleagues sang his praises.

Zamolodchikov is “one of the most accomplished theoretical physicists worldwide,” George Sterman, Director of the C.N. Yang Institute for Theoretical Physics and Distinguished Professor at Stony Brook University’s Department of Physics and Astronomy, said in a statement. “He has made groundbreaking advances, with enormous impact in many physics fields, such as condensed matter physics, quantum statistical physics and high energy physics, including our understanding of fundamental matter and forces.”

Sterman added that Zamolodchikov’s insights have influenced the way theoretical physicists think about foundational concepts.

“Having such a giant in your institute is always great,” said van Nieuwenhuizen, who said the two Breakthrough Prize winners sometimes discuss physics problems together, although their fields differ.

Founded by Sergey Brin, Priscilla Chan and Mark Zuckerberg, Julia and Yuri Milner and Anne Wojcicki, the Breakthrough Prizes are referred to as the “Oscars of science.”

A scientific throwback

Zamolodchikov has a “very pleasant personality” and couldn’t be a better neighbor in a corridor in which five of the offices house distinguished professors, van Nieuwenhuizen said.

Van Nieuwenhuizen, who was a deputy for C.N. Yang for six years, said the two of them often discussed whether to continue to build a theoretical physics department or to branch out into applied physics.

The direction for the department “wasn’t so obvious at the time” but the institute members decided to continue to build a fundamental physics group, which attracted the “right people. In hindsight, it was the right decision,” van Nieuwenhuizen added.

In some of his lectures and discussions, Zamolodchikov, who often pushes his glasses up on his forehead, works with equations he writes on a blackboard with chalk.

He suggested that many in the audience prefer the slow pace of the blackboard and he uses it when appropriate, including in class lectures. Having grown up in pre-computer times, he considers the blackboard his “friend.”

“He’s a throwback,” said van Nieuwenhuizen. “I happen to think that is the best way of teaching.”

Thinking about eating bread

Zamolodchikov said he often gives his work considerable thought, which he believes many scientists do consciously and subconsciously, wherever they are and what they are doing.

When his daughter Dasha was about four years old, she asked him what he was thinking about all the time. He joked that he was contemplating “how to consume more white bread.”

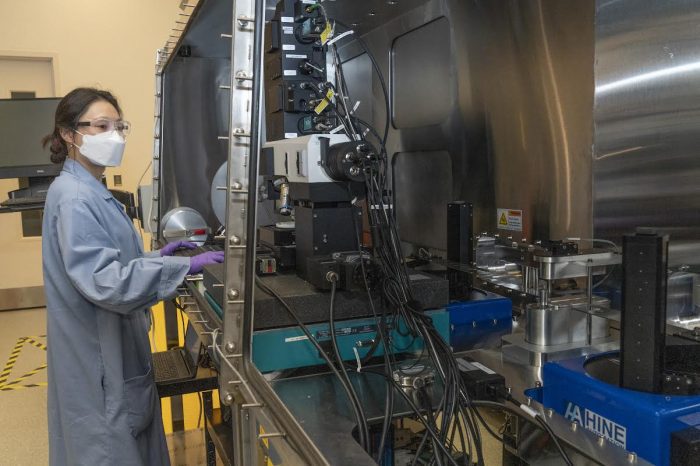

Even today, Dasha, who conducts biological research, asks if he is “still thinking about white bread.”

Family commitment to physics

When Zamolodchikov’s father Boris returned from World War II, the Soviet Union built a physics institute in his town of Dubna.

His father had an “exceptional understanding” of some parts of physics, such as electromagnetic theory and he would talk in their house about science. Boris Zamolodchikov was chief engineer of a laboratory that was working on the first cyclotron.

“He convinced us that physics was something to devote the life to,” Zamolodchikov explained.

Zamolodchikov (who goes by the name “Sasha”) and his late twin brother Alexei (who was known as Alyosha) looked strikingly similar, but were never sure whether they were fraternal or identical twins. The twins collaborated on research in physics until Alexei died in 2007.

Zamolodchikov and his brother understood each other incredibly well. One of them would share a thought in a few words and the other would understand the idea and concept quickly.

“It was some sort of magic,” said Zamolodchikov. “I miss him greatly.”

Indeed, even recently, Zamolodchikov has been working to solve a problem. He recalls that his brother told him he knew how to solve it, but the Stony Brook Distinguished Professor forgot to ask him about the details.

When Zamolodchikov, who thinks of his twin brother every day, learned he had won the prize, he said he feels “like I share this honor with him.”

Description of his work

In explaining his work, Zamalodchikov suggests that quantum field theory, which was questioned for some time before the mid-1970’s, has been used to describe subatomic physics.

On a general level, quantum field theory helps explain nature in terms of degrees of freedom.

“I was trying to solve simplified versions of these field theories,” said Zamolodchikov. He provided insights into what quantum field theory can describe and what kind of physical behavior would never come from quantum field theory.

His work shed light on phase transitions, from liquids to gases. He was able to find a solution through quantum field theory that had a direct application in explaining phase transition.

Experimentalists did the experiment and found the signature he expected.

“When I make a prediction about the behavior in phase transition and they do the experiment and find it exactly as my prediction, it’s remarkable,” he said. “My prediction involves an exceptionally complicated but beautiful mathematical structure.”