By Erika Riley

After a month-long break this holiday season, Stony Brook University’s Staller Center returns for the second half of its 2016-17 season with compelling performances. There is something for everybody, and you won’t want to miss out on these exciting shows.

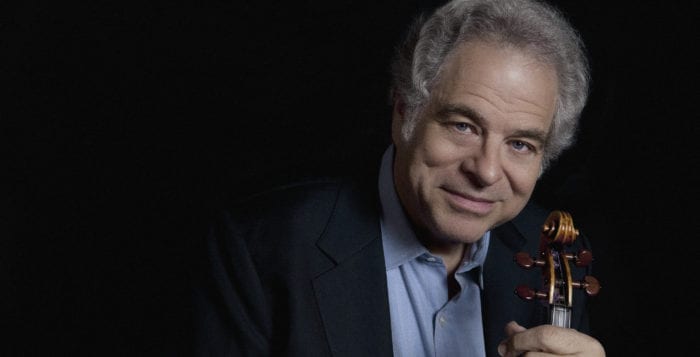

“The second half of the Staller Center season really shows the diversity of our programs to fill the broad and varied tastes of our students, faculty, staff and greater community,” said Alan Inkles, director of Staller Center for the Arts. “Shows range from the world’s greatest violinist, Itzhak Perlman, to a spectacular cirque show, “Cuisine & Confessions” featuring aerealists, jugglers and acrobats and boasts a full kitchen where the cast cooks for our audience.

Inkles continued, “We truly span the arts in every format this spring. Bollywood’s finest song and dance routines will abound in Taj Express; Off Book/Out of Bounds with Brooklyn Rundfunk Orkestrata will add their pop/rock take on famous Broadway tunes; dance explodes as the Russian National Ballet Theatre brings a program with two story ballets, ‘Carmen’ and ‘Romeo & Juliet.’ The impeccable Martha Graham Dance Company brings their modern dance fire to Staller. Jazz abounds with award-winning artists including pianist Vijay Iyer and singer Cécile McLorin Salvant. There’s of course much more and with continued private and corporate support, we continue to keep ticket prices reasonable for everyone to attend and to attend often!”

Musical performances

On Feb. 19 at 7 p.m., Peter Kiesewalter, founder of the East Village Opera Company and Brooklyn Runkfunk Orkestrata, will be leading a high-energy rock show titled Off Book/Out of Bounds. The show, held in the Recital Hall, will feature a four-piece rock band performing rock versions of well-loved theater songs. Tickets are $42.

Grammy-nominated composer and pianist Vijay Iyer will be performing with his sextet in the Recital Hall on Feb. 25 at 8 p.m.. Described by The New Yorker as “jubilant and dramatic,” he plays pure jazz that is currently at the center of attention in the jazz scene. Tickets are $42.

The Staller Center’s 2017 Gala will take place on March 4 at 8 p.m. on the Main Stage and will feature violinist Itzhak Perlman. Perlman is the recipient of over 12 Grammys and several Emmys and worked on film scores such as “Schindler’s List” and “Memoirs of a Geisha.” Tickets are $75 and Gala Supporters can also make additional donations to enhance Staller Center’s programs and educational outreach activities.

Starry Nights returns to the Recital Hall on March 8 at 8 p.m. this year under the direction of Colin Carr, who will also be performing cello during the program. Artists-in-Residence at Stony Brook will be playing beautiful classics such as Vivaldi’s Violin Concerto and Schubert’s Piano Trio #3 in E flat major. Tickets are $38.

Newly added to the roster is singer, songwriter and pianist Peter Cincotti who will perform an intimate concert in the Recital Hall on March 9 at 8 p.m. Named “one of the most promising singer-pianists of the next generation” by the New York Times, Cincotti will be featuring his newest album, Long Way From Home. With a piano, a bench, a microphone and his band, Cincotti will take his audience on a breathtaking musical ride. Tickets are $30.

The Five Irish Tenors will be performing a lineup of beloved Irish songs and opera on March 18 at 8 p.m., the day after St. Patrick’s Day. Songs include “Down by the Sally Gardens,” “Will You Go Lassie Go” and “Danny Boy.” Tickets to the concert, taking place in the Recital Hall, are $42.

The award-winning Emerson String Quartet, with Eugene Drucker, Philip Setzer, Lawrence Dutton and Paul Watkins, will return on April 4 at 8 p.m. in the Recital Hall. The program will feature works by Dvorak, Debussy and Tchaikovsky. Tickets are $48.

Cecile McLorin Salvant will close out the musical performances of the season on April 29 at 8 p.m. in the Recital Hall with unique interpretations of blues and jazz compositions with the accompaniment of Sullivan Fortner on piano. Salvant is a Grammy award winner and has returned to the Staller Center after popular demand from her 2013 performance. The performance is sure to be theatrical and emotional. Tickets are $42.

Dance performances

Staller Center’s first dance performance of 2017 is sure to be a hit. Taj Express will be performing on Feb. 11 at 8 p.m., delivering a high-energy performance of Bollywood dances, celebrating the colorful dance and music of India. Through a fusion of video, dance and music, the ensemble will take you on a magical journey through modern Indian culture and society; this full-scale production will fuse east and west with classical dance steps, sexy moves and traditional silks and turbans. The extravagant performance will take place on the Main Stage, and tickets are $48.

The Russian National Ballet Theatre will be performing on the Main Stage on March 11 at 8 p.m. Created in Moscow, the Ballet Theatre blends the timeless tradition of classical Russian ballet with new developments in dance from around the world. The Ballet Theatre will be performing both “Carmen” and “Romeo & Juliet.” Tickets are $48.

Canada’s award-winning circus/acrobat troupe, Les 7 doigts de la main (7 Fingers of the Hand), will be performing their show Cuisine & Confessions on the Main Stage on April 1 (8 p.m.) and April 2 (2 p.m.) The show is set in a kitchen and plays to all five of the senses, mixing acrobatic cirque choreography and pulsating music with other effects, such as the scents of cookies baking in the oven, the taste of oregano and the touch of hands in batter. A crowd pleaser for all ages, tickets are $42.

The last dance performance of the season will be on April 8 at 8 p.m. by the Martha Graham Dance Company. The program will showcase masterpieces by Graham alongside newly commissioned works by contemporary artists inspired by Graham. The dance performance will take place on the Main Stage and tickets are $48.

Not just for kids

The ever unique Cashore Marionettes will be presenting a show called Simple Gifts in the Recital Hall on March 26 at 4 p.m. The Cashore Marionettes will showcase the art of puppetry through humorous and poignant scenes set to music by classics like Vivaldi, Beethoven and Copland. Tickets to see the engineering marvels at work are $20.

The Met: Live in HD

The Metropolitan Opera HD Live will be returning once again to the Staller Center screen. The screenings of the operas feature extras such as introductions and backstage interviews. There will be seven screenings throughout the second half of the season: “L’amour de Loin” on Jan. 14, “Romeo et Juliette” on Jan. 21, “Rusalka,” on Feb. 26, “La Traviata” on March 12, “Idomeneo” on April 9, “Eugene Onegin” on May 7 and “Der Rosenkavalier” on May 13. The screenings are all at 1:00 p.m., except for “Der Rosenkavalier,” which is at 12:30 p.m. For a full schedule and to buy tickets, visit www.stallercenter.com or call at 631-632-ARTS.

Films

As always, the Staller Center will be screening excellent films throughout the upcoming months. Through April 28, two movies will be screened on Friday evenings: one at 7 p.m. and one at 9 p.m. On Feb. 3, “Newtown,” a documentary about the Sandy Hook shooting, and “Loving,” a story of the first interracial marriage in America will both screen. “American Pastoral,” starring Ewan McGregor, Jennifer Connelly and Dakota Fanning will screen on Feb. 17; and “Jackie,” starring Natalie Portman, will screen on March 24. The season will finish off on April 28 with “Hidden Figures,” a true story of the African American female mathematicians who worked for NASA during the space race, and “La La Land,” a modern-day romantic musical starring Emma Stone and Ryan Gosling.

Tickets to the movie screenings are $9 for adults, $7 for students, seniors and children and $5 SBU students. Tickets for the shows and films may be ordered by calling 631-632-2787. Order tickets online by visiting www.stallercenter.com.

About the author: Stony Brook resident Erika Riley is a sophomore at Knox College in Galesburg, Illinois. She recently interned at TBR during her winter break and hopes to advance in the world of journalism and publishing after graduation.