1 of 47

Ward Melville senior Sophia DiGirolamo sets the play in the Suffolk Class AA championship game against Commack. Bill Landon photo

Ward Melville senior Jasmine Gandolfo from the service line in the Suffolk Class AA championship game against Commack. Bill Landon photo

Patriots battle at the net in the Suffolk Class AA championship game against Commack. Bill Landon photo

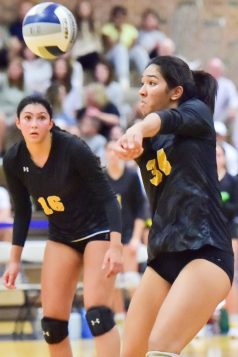

Ward Melville senior Gianna Hogan keeps the ball in play in the Suffolk Class AA championship game against Commack. Bill Landon photo

Ward Melville senior Sophia DiGirolamo puts the play in the Suffolk Class AA championship game against Commack. Bill Landon photo

Ward Melville senior Alexa Gandolfo spikes at net in the Suffolk Class AA championship game against Commack. Bill Landon photo

Ward Melville senior Sophia DiGirolamo sets the ball in the Suffolk Class AA championship game against Commack. Bill Landon photo

Ward Melville senior Sophia DiGirolamo keeps the ball in play in the Suffolk Class AA championship game against Commack. Bill Landon photo

Ward Melville sophomore Emma Bradshaw puts the ball in play in the Suffolk Class AA championship game against Commack. Bill Landon photo

Ward Melville senior Bailee Williams attacks at net in the Suffolk Class AA championship game against Commack. Bill Landon photo

Ward Melville senior Jasmine Gandolfo returns the ball in the Suffolk Class AA championship game against Commack. Bill Landon photo

Ward Melville senior Gianna Hogan digs one out in the Suffolk Class AA championship game against Commack. Bill Landon photo

Commack junior Molly Singer with a save in the Suffolk AA championship game against Ward Melville. Photo by Bill Landon

Commack junior Maya Khan keeps the ball in play in the Suffolk AA championship game against Ward Melville. Photo by Bill Landon

Commack junior Molly Singer saves the play in the Suffolk AA championship game against Ward Melville. Photo by Bill Landon

Commack co-captain Mikalah Curran drops one over the net in the Suffolk AA championship game against Ward Melville. Photo by Bill Landon

Commack junior Rylie Curran sets the play in the Suffolk AA championship game against Ward Melville. Photo by Bill Landon

Commack co-captain Emma Santa Maria keeps the ball in play in the Suffolk AA championship game against Ward Melville. Photo by Bill Landon

Commack junior Molly Singer sets the play in the Suffolk AA championship game against Ward Melville. Photo by Bill Landon

Ward Melville sophomore Emma Bradshaw keeps the ball in play in the Suffolk Class AA championship game against Commack. Bill Landon photo

Ward Melville senior Mackenzie Heaney returns the ball in the Suffolk Class AA championship game against Commack. Bill Landon photo

Commack junior Molly Singer sets the play in the Suffolk AA championship game against Ward Melville. Photo by Bill Landon

Ward Melville junior Kelsey McCaffrey digs one out in the Suffolk Class AA championship game against Commack. Bill Landon photo

Commack junior Rylie Curran digs one out in the Suffolk AA championship game against Ward Melville. Photo by Bill Landon

Ward Melville senior Sophia DiGirolamo keeps the ball in play in the Suffolk Class AA championship game against Commack. Bill Landon photo

Commack junior Maya Khan saves the play in the Suffolk AA championship game against Ward Melville. Photo by Bill Landon

Commack sophomore Chloe Masciovecchio from the service line in the Suffolk AA championship game against Ward Melville. Photo by Bill Landon

Commack junior Maya Khan with a kill shot in the Suffolk AA championship game against Ward Melville. Photo by Bill Landon

Ward Melville senior Jasmine Gandolfo serves the ball in the Suffolk Class AA championship game against Commack. Bill Landon photo

Commack co-captain Mikalah Curran sets the play in the Suffolk AA championship game against Ward Melville. Photo by Bill Landon

Commack junior Molly Singer saves the play in the Suffolk AA championship game against Ward Melville. Photo by Bill Landon

Ward Melville senior Sophia DiGirolamo with a kill shot in the Suffolk Class AA championship game against Commack. Bill Landon photo

Commack sophomore Kaitlan Curran with a kill shot in the Suffolk AA championship game against Ward Melville. Photo by Bill Landon

Ward Melville senior Sophia DiGirolamo with a kill shot in the Suffolk Class AA championship game against Commack. Bill Landon photo

Commack senior Mikalah Curran with a kill shot in play in the Suffolk AA championship game against Ward Melville. Photo by Bill Landon

Commack senior Julie Thomas with a kill shot in play in the Suffolk AA championship game against Ward Melville. Photo by Bill Landon

Commack senior Marissa Pagnutti keeps the ball in play in the Suffolk AA championship game against Ward Melville. Photo by Bill Landon

Ward Melville won the first set by 10 points, looking to make it a clean sweep in the Suffolk Class AA volleyball championship Monday night, Nov. 7. However, the Commack Cougars edged the Patriots, 29-17, in the second set and 26-24 in the third.

Commack, the No. 4 seed, took command of the fourth set, picking off the Patriots, 25-20, for the county title.

Commack co-captain Mikalah Curran had 26 kills and 14 digs, and her younger sister Kaitlin killed 8, had 15 digs and two service aces.

The win lifts the Commack girls volleyball team to 14-2 this season, and they will take on Massapequa for the Long Island Championship game at Hauppauge High School on Thursday, Nov. 10. First service is slated for 5 p.m.