By Daniel Dunaief

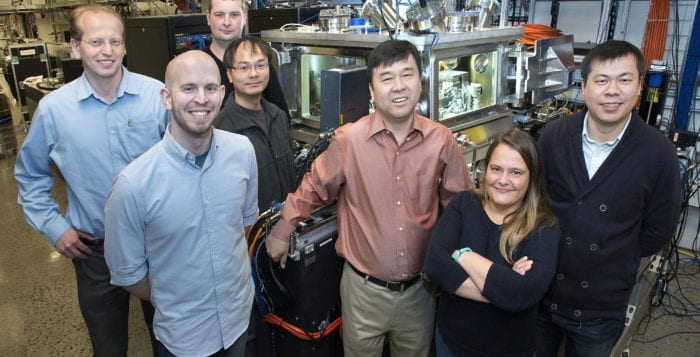

One day, the tool 375 people from 29 countries came to discuss in late July at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory may help eradicate malaria, develop treatments for cancer and help understand the role various proteins play in turning on and off genes.

Eager to interact with colleagues about the technical advances and challenges, medical applications and model organisms, the participants in Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory’s third meeting on the CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing system filled the seats at Grace Auditorium.

“It’s amazing all the ways that people are pushing the envelope with CRISPR-Cas9 technology,” said Jason Sheltzer, an independent fellow from Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory who presented his research on a breast cancer treatment.

The technology comes from a close study of the battle between bacteria and viruses. Constantly under assault from viruses bent on commandeering their genetic machinery, bacteria figured out a way of developing a memory of viruses, sending out enzymes that recognize and destroy familiar invaders.

By tapping into this evolutionary machinery, scientists have found that this system not only recognizes genes but can also be used to slice out and replace an errant code.

“This is a rapidly evolving field and we continue to see new research such as how Cas1 and Cas2 recognize their target, which opens the door for modification of the proteins themselves, and the recent discovery of anti-CRISPR proteins that decrease off-target effects by as much as a factor of four,” explained Jennifer Doudna, professor of chemistry and molecular and cell biology at the University of California at Berkeley and a meeting organizer for the last three years, in an email.

Austin Burt, a professor of evolutionary genetics at the Imperial College in London, has been working on ways to alter the genes of malaria-carrying mosquitoes, which cause over 430,000 deaths each year, primarily in Africa.

“To wipe out malaria would be a huge deal,” Bruce Conklin, a professor and senior investigator at the Gladstone Institute of Cardiovascular Disease at the University of California in San Francisco and a presenter at the conference, said in an interview. “It’s killed millions of people.”

This approach is a part of an international effort called Target Malaria, which received support from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation.

To be sure, this effort needs considerable testing before scientists bring it to the field. “It is a promising approach but we must be mindful of the unintended consequences of altering species and impacting ecosystems,” Doudna cautioned.

In an email, Burt suggested that deploying CRISPR in mosquitoes across a country was “at least 10 years” away.

CSHL’s Sheltzer, meanwhile, used CRISPR to show that a drug treatment for breast cancer isn’t working as scientists had thought. Researchers believed a drug that inhibited the function of a protein called maternal embryonic leucine zipper kinase, or MELK, was halting the spread of cancer. When Sheltzer knocked out the gene for MELK, however, he discovered that breast cancer continued to grow or divide. While this doesn’t invalidate a drug that may be effective in halting cancer, it suggests that the mechanism researchers believed was involved was inaccurate.

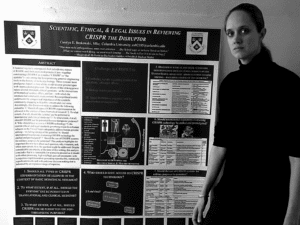

Researchers recognize an array of unanswered questions. “It’s premature to tell just how predictable genome modification might be at certain levels in development and in certain kinds of diseases,” said Carolyn Brokowski, a bioethicist who will begin a position as research associate in the Emergency Medicine Department at the Yale School of Medicine next week. “In many cases, there is considerable uncertainty about the causal relationship between gene expression and modification.”

Brokowski suggested that policy makers need to appreciate the “serious reasons to consider limitations on nontherapeutic uses for CRISPR.”

Like so many other technologies, CRISPR presents opportunities to benefit mankind and to cause destruction. “We can’t be blind to the conditions in which we live,” said Brokowski.

Indeed, Doudna recently was one of seven recipients of a $65 million Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency award to improve the safety and accuracy of gene editing.

The funding, which is for $65 million over four years, supports a greater understanding of how gene editing technologies work and monitors health and security concerns for their intentional or accidental misuse. Doudna, who is credited with co-creating the CRISPR-Cas9 system with Emmanuelle Charpentier a scientific member and director of the Max Planck Institute for Infection Biology in Berlin, will explore safe gene editing tools to use in animal models and will specifically target Zika and Ebola viruses.

“Like most misunderstood disruptive technologies, CRISPR outpaced the necessary policy and regulatory discussions,” Doudna explained. The scientific community, however, “continued to advance the technology in a transparent manner, helping to build public awareness, trust and dialogue. As a result, CRISPR is becoming a mainstream topic and the public understanding that it can be a beneficial tool to help solve some of our most important challenges continues to grow.”

Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory plans to host its fourth CRISPR meeting next August, when many of the same scientists hope to return. “It’s great that you can see how the field and scientific community as a whole is evolving,” Sheltzer said.

Doudna appreciates the history of Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, including her own experiences. As a graduate student in 1987, Doudna came across an unassuming woman walking the campus in a tee-shirt: Nobel Prize winner Barbara McClintock. “I thought, ‘Oh my gosh, this is someone I revere,” Doudna recalled. “That’s what life is like” at the lab.

Brokowski also plans to attend the conference next year. “I’m very interested in learning about all the promises CRISPR will offer,” she said. She is curious to see “whether there might be more discussion about ethical and regulatory aspects of this technology.”