When Alan Calder was young, his father used to share the world of the planets and stars with him through telescopes in their backyard. Peter Tarr, meanwhile, drew pictures in his teenage notebooks of Saturn and Jupiter and saved enough money to travel to Africa aboard a ship with Neil Armstrong to view a solar eclipse.

This past week, Calder, Tarr, and many others who have craned their necks skyward received the first set of clear images from Pluto, a dwarf planet located more than three billion miles from Earth.

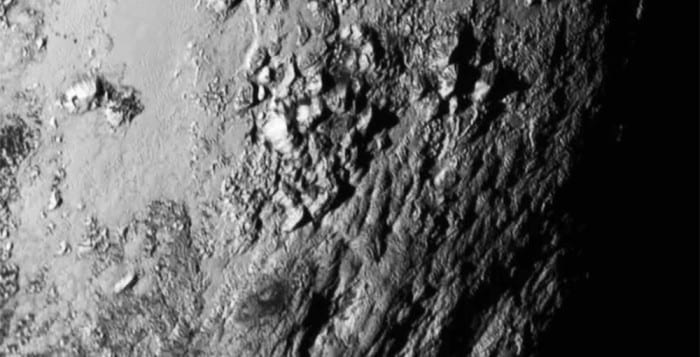

The New Horizons space probe, which the National Aeronautics and Space Administration blasted off from Earth in 2006, beamed back the first pictures of a dwarf planet that had, up until recently, been considered something of a gray, icy blob.

Traveling at the speed of light, the images took four and a half hours to reach the eager eyes of astronomers and scientists around the world. Long Islanders shared the excitement surrounding these first close-up views of a planet named, by then 11-year old Venetia Burney, more than eight decades ago.

“Our imaginations tend to fail us” when anticipating what’s around the corner or, more precisely, billions of miles away, said Frederick Walter, a professor of astronomy who specializes in stars and teaches a solar system course at Stony Brook. Pluto “doesn’t look like any of the worlds we know.”

Astronomers have zeroed in on the 11,000 foot high ice mountains, which, NASA scientists said, are likely made of a combination of ice and frozen methane and nitrogen.

The show stopper in these early images, however, was the lack of something many of them were sure would be there: impact craters. These craters are like the ones that riddle the surface of Earth’s moon and that have also affected the geology of our planet.

“Some process has been resurfacing this planet, to smooth it out and get rid of whatever craters it should have,” said Deanne Rogers, an assistant professor in the Department of Geosciences at Stony Brook. “That was a real surprise for me.”

At this point, any explanation of the process that might melt and smooth out the surface of a planet that takes 248 years to orbit the sun is speculation, Rogers added.

One such possibility is the presence of radioactive elements, researchers said.

Calder, who is an associate professor in the Department of Physics and Astronomy at Stony Brook, said he, too, is “intrigued by what seems to be the smooth surface of the planet. That implies an active geology.”

Calder’s research is in the field of star explosions. He said the images and information from Pluto wouldn’t impact his work too directly, unless scientists were able to show an interesting ratio of unexpected isotopes.

Calder said he’s looking forward to watching the textbooks change and seeing an alteration in the curriculum of classes on the solar system in light of the new images from the New Horizons satellite that are returning at such a slow pace that it will take 16 months for NASA to collect them all.

The active geology of this distant dwarf planet suggests that “even a small cold body that far out has activity on it,” Calder said.

For Tarr, a senior science writer at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, his interest in the planets date back to his teens. Traveling aboard a boat toward Africa to observe a solar eclipse, Tarr rubbed elbows with author Isaac Asimov, astronaut Armstrong, thousands of others interested in astronomy and fellow teenager Neil deGrasse Tyson, who would become an astrophysicist, author and director of the Hayden Planetarium.

For Tarr, some of the heroes of the Pluto images are the scientists who figured out, more than a decade ago, how to plot a course from Earth that would take the New Horizons spacecraft within 7,800 miles of Pluto.

“The calculation that goes into the launch is an incredible achievement,” Tarr said.

For Walter, part of the excitement of seeing these images comes from interpreting and understanding the unexpected parts of the picture.

“If you anticipated everything, you’d be doing the wrong thing,” Walter said. “Now that they’ve got these images” some of the old ideas will get “tossed out, and they’ll bring in something new” to explain the lack of craters, he added.