By Heidi Sutton

Who doesn’t love a good fairy tale, especially one like “Cinderella,” which is reputed to be one of the most adapted and re-interpreted children’s stories of all time?

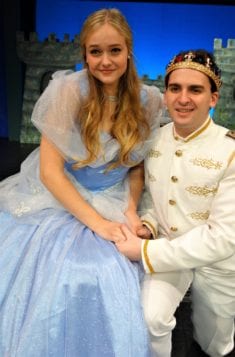

To the delight of all the little princesses out there, Theatre Three in Port Jefferson kicks off its 2019-20 children’s theater season with an original musical retelling of the “rags to riches” tale through Aug. 9. With book, music and lyrics by Douglas J. Quattrock, this version of “Cinderella” combines Charles Perrault’s classic tale with Mark Twain’s “The Prince & the Pauper” to produce a lovely afternoon at the theater.

Perrault (Steven Uihlein) serves as narrator as well as “squire to the sire” and transports audiences to the kingdom of King Charming (Andrew Lenahan) who wishes to retire to Boca Raton and pass the crown to his son, Prince Charming (Matt Hoffman). However, the king feels that his son should get married first and invites all eligible maidens to a royal ball.

The squire delivers the invitations to the home of Cinderella (Meg Bush) who after 300 years is still being treated badly by her stepmother Lady Jaclyn (Nicole Bianco) and stepsisters Gwendolyn (Michelle LaBozzetta) and Madeline (Krystal Lawless). When Cinderella asks if she can go to the ball, her stepmother tells her she has to do all her chores first, including washing the cat, but we all know how that ends.

Left behind while the step meanies go to the ball, the poor girl is visited by her fairy godmother, Angelica (Emily Gates) who cooks up a beautiful gown and sends her on her way.

Meanwhile, the prince concocts a plan to switch places with the squire in hopes of meeting a girl who will like him “for who he is, not what he is.” Things go horribly wrong at the ball, thanks to the ill-mannered stepsisters, and it ends before Cinderella can get there. When she finally arrives, Cinderella is greeted by a squire (the prince) who asks her to dance because “the band is paid till 1.” Will she take him up on his offer? Will they waltz the night away?

Directed by Jeffrey Sanzel, the eight-member cast does an excellent job in portraying this adorable story. One of the funniest scenes is when the prince and squire show up at Cinderella’s house with the glass slipper and the stepsisters and even stepmother try it on with the same result: “I think it’s on. All hail the queen! Ouch, take it off!”

Accompanied on piano by Douglas J. Quattrock, all of the sweet musical numbers are wonderfully choreographed by Nicole Bianco, with a special nod to “Please, Mother, Please!” and “A Girl Like Me (and a Boy Like You).”

The costumes, designed by Teresa Matteson and Toni St. John, are flawless, from the royal garbs worn by the king and prince to the fancy gowns worn at the ball. The wings on the fairy godmother even light up — a nice touch. Lighting design by Steve Uihlein along with some special effects pull it all magically together.

If you’re looking for something to do with the kids for the summer, Theatre Three’s “Cinderella” fits the bill perfectly. Souvenir wands are sold before the show and during intermission. Meet the cast in the lobby after the show.

Theatre Three, 412 Main St. in Port Jefferson presents “Cinderella” through Aug. 9. Children’s theater continues with “Pinocchio” from Aug. 2 to 10; and “A Kooky Spooky Halloween” from Oct. 5 to 26. All seats are $10. For more information or to order, call 631-928-9100 or visit www.theatrethree.com. See more photos online at www.tbrnewsmedia.com.

Photos by Peter Lanscombe, Theatre Three Productions Inc.

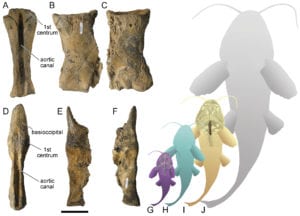

O’Leary suggested that the paper provides some context for climate and sea level changes that can and have occurred. During the period she studied, the Earth was considerably warmer, with over 40 percent of today’s exposed land covered by water. Sea levels were about 300 meters higher than current levels, although the Earth wasn’t home to billions of humans yet or to many of the modern day species that share the planet’s resources.

O’Leary suggested that the paper provides some context for climate and sea level changes that can and have occurred. During the period she studied, the Earth was considerably warmer, with over 40 percent of today’s exposed land covered by water. Sea levels were about 300 meters higher than current levels, although the Earth wasn’t home to billions of humans yet or to many of the modern day species that share the planet’s resources. O’Leary said that much of the literature for the science in Mali was in French, which had kept it a bit below the radar for scientific discourse, which tends to be in English.

O’Leary said that much of the literature for the science in Mali was in French, which had kept it a bit below the radar for scientific discourse, which tends to be in English.