By Daniel Dunaief

This is part two of a two-part series featuring Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory alums Joanna Wysocka, Robert Tjian, Victoria Bautch, Rasika Harshey and Eileen White.

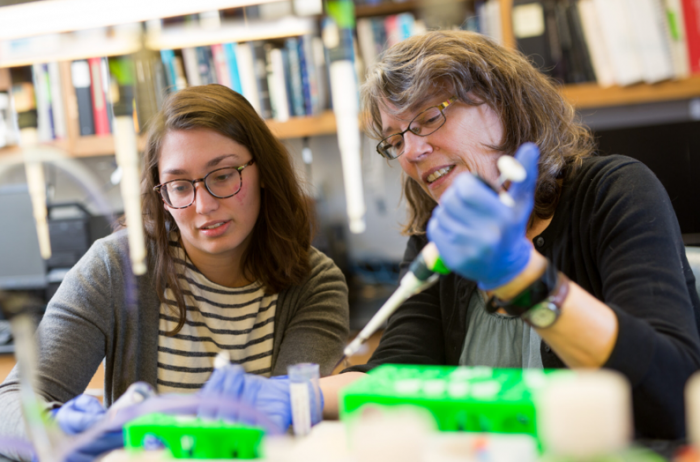

Often working seven days a week as they build their careers, scientists plan, conduct and interpret experiments that don’t always work or provide clear cut results.

Driven by their passion for discovery, they tap into a reservoir of ambition and persistence, eager for that moment when they might find something no one else has discovered, adding information that may lead to a new technology, that could possibly save lives, or that leads to a basic understanding of how or why something works.

Nestled between the shoreline of an inner harbor along the Long Island Sound and deciduous trees that celebrate the passage of seasons with technicolor fall foliage, Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory has been a career-defining training ground for future award-winning scientists.

Last week two alumni of Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Joanna Wysocka and Robert Tjian, shared their thoughts, experiences, and reflections on the private lab that was founded in 1890. This week the article continues with reflections from alumni Rasika Harshey, Victoria Bautch and Eileen White.

Confidence builder

Lunch time presented no break from science for Rasika Harshey, and that was just as she’d hoped.

When she was at Blackford Hall between 1979 and 1983, first as a postdoctoral researcher and then as a staff investigator in the lab of Ahmad Bukhari, Harshey said conversations frequently included discussions about research. “It was wonderful,” she said. “It was just science, 24/7.”

Bukhari was studying a virus that infects bacteria, called mu, for mutator. The viral particle genome was jumping into the host genome. “At that point, transposable elements” of DNA were “entering into our consciousness,” Harshey explained.

In her research, Harshey would induce the virus and, 30 minutes later, get 100 phage particles. Looking in the cytoplasm, however, she didn’t find any of this viral DNA until phage progeny appeared about 50 minutes later. “How is that possible?” she asked. “I wanted to solve this mystery.”

Harshey spent countless hours in the electron microscope room, isolating DNA. She knew mu was replicating, or copying itself, but she couldn’t figure out how or what it was doing. She and Bukhari proposed a model about transposable elements at a meeting called “Movable Genetic Elements” in 1979 at CSHL that generated considerable discussion.

“It was thrilling at the time for me to develop as a scientist,” Harshey said. “It seemed to me that I was saying something and people were listening. I gained a lot of confidence in myself.” The work she did turned out to be only partially correct, but it gave her the sense that she could solve problems.

With CSHL as a backdrop, Harshey enjoyed the opportunity to attend meetings and to interact with other visitors and other scientists on campus. “It was a total immersion” she said. “Summers were magical, with so many meetings one could just walk into.”

Harshey visited Barbara McClintock’s lab, which was down the hall from hers. McClintock, who won the Nobel Prize in Harshey’s final year at CSHL, showed her the maize cells.

McClintock also invited her to her cottage, where she served what Harshey recalled was a “delicious” poppyseed cake.

She described McClintock as “quiet” and a “tough cookie.”

Harshey thought it was inspiring to be with McClintock, Watson and Richard Roberts, who also won a Nobel Prize. She also appreciated the opportunity to visit with Guenter Albrecht-Buehler and Joseph Sambrook. “I was in and out of Richard Roberts’s lab all the time,” she said.

For her work, Harshey needed restriction enzymes, which Phyllis Myers produced. She had to “beg” Myers for these valuable enzymes that were in short supply.

Harshey felt an urgency to commit herself to her work. When she and her husband Makkuni Jayaram were expecting a baby, she didn’t share the news until it had become obvious. She worked until the last moment before the baby was born in 1982, “but I came back,” she said.

Harshey, who also calls CSHL “home,” described it as a “place time forgot. It’s quiet and beautiful and you can do and think and talk science.” Professor in Molecular Biosciences at The University of Texas at Austin in the College of Natural Sciences, Harshey is grateful for the career and the life she’s led. “A series of accidents got me here,” she said. “I can’t believe my good fortune, that I get to do what I get to do every day.”

As a part of the history of CSHL, Harshey appreciates a culture that she has carried forward in her career. The “deep joy, commitment, excitement for biology, particularly for designing experiments, and looking at a problem from all angles” was embedded into the approach scientists took to the work they did at the lab.

She also believes the tradition at CSHL includes an “appreciation for how easy it is to get things wrong and to continually challenge your own ideas.”

Intense culture

Victoria Bautch came to Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory in the 1983 knowing that she was interested in studying aspects of developmental biology. When she saw the power of the new technology, she started working on genetically modified animals.

She was trying to figure out whether viral genes previously only linked to cancer by association could cause cancer when part of the genome was put into animals. When she inserted genes into a mouse’s DNA, some of these mice developed tumors in their blood vessels. She “didn’t know this was going to happen,” she said. “The type of tumor was a complete surprise.”

Bautch needed to know more about how blood vessels formed and functioned to understand these tumors. That’s what got her excited about studying these blood vessels. These blood vessel tumors “weren’t on my radar,” she said.

While working in the lab of Doug Hanahan, Bautch had the opportunity to interact with Judah Folkman, a Professor at Harvard University. Folkman was excited about the way these blood vessels were developing and encouraged Bautch to continue to work in this field. Folkman championed the idea that new blood vessel formation contributes to the progression of many types of tumors. He was eager to bring new people and technologies into the field.

Bautch also met mouse geneticists Nancy Jenkins and Neal Copeland who were at Jackson Labs at the time and were instrumental in her career progression. She started asking basic questions about how blood vessels forms and how they function.

Folkman was looking to “bring people into the field that had more of a basic science and molecular biology background,” Bautch said. He was hoping to add researchers who would use the new tools to understand blood vessel basics and how they are involved in tumors.

The tumor Bautch worked on was an “entree into the bigger field of blood vessels and vascular biology,” she said.

Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory provided a constructive backdrop for the work Bautch did that proved important in her career. “I was looking for an intense and very high caliber scientific environment and I feel like I found it,” she said.

Indeed, Bautch often worked seven days a week, starting at 10 or 11 in the morning and ending around 1 or 2 in the morning. During the later hours, she had an easier time accessing machines and equipment that others in the lab also needed.

Like Harshey, Bautch has her own McClintock story. “She always would say, ‘Look at your organism very carefully.’ You could learn so much from observing.”

At the time, McClintock’s advice seemed “antiquated” to Bautch, especially with researchers doing molecular biology that was more of a technological breakthrough, but now appreciates the guidance. “A really important piece of being a scientist is being observant,” she explained.

Bautch said other scientists were prepared to offer their responses to her work. “People were always telling you what they thought, whether you wanted it or not,” she recalled.

Now a Distinguished Professor of Biology and Co-Director of the McAlister Heart Institute at UNC Chapel Hill, Bautch recalls her time at CSHL as a combination of a “very intense life experience as well as science experience.” As for her hopes for the current crop of scientists at CSHL, Dr. Bautch hopes this generation is “more inclusive.”

An alternate explanation of cancer

Around the same time that actress Heather Locklear was telling TV audiences about Faberge Organics Shampoo about how people can tell two friends about the shampoo who then tell two friends, researchers knew that a type of gene that promoted cancer did essentially the same thing.

Called an oncogene, these genes caused cells to continue to divide and, as the shampoo commercial suggested “and so on and so on and so on.” Back then, scientists focused on the role oncogenes played in cell proliferation, which, with cancer, involved the runaway copying of itself.

A graduate of Smithtown High School who earned her PhD at Stony Brook University, Eileen White joined Bruce Stillman’s lab as a post doctoral fellow at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory in 1983. After three years, White became a staff investigator, making the beginning of career-defining discoveries about the development of cancer.

“We knew that certain viruses cause cancer, and we knew that these viruses encoded oncogenes,” said Dr. White. “The whole idea was to understand how.”

Indeed, viral oncogenes, which are small and less complicated than tumor genomes, presented the opportunity to find a shortcut to understand how cancers developed in humans. Even if the human oncogene is small, the genome it sits in is huge, which is not the case of a viral oncogene that sits I a very small viral genome, she explained.

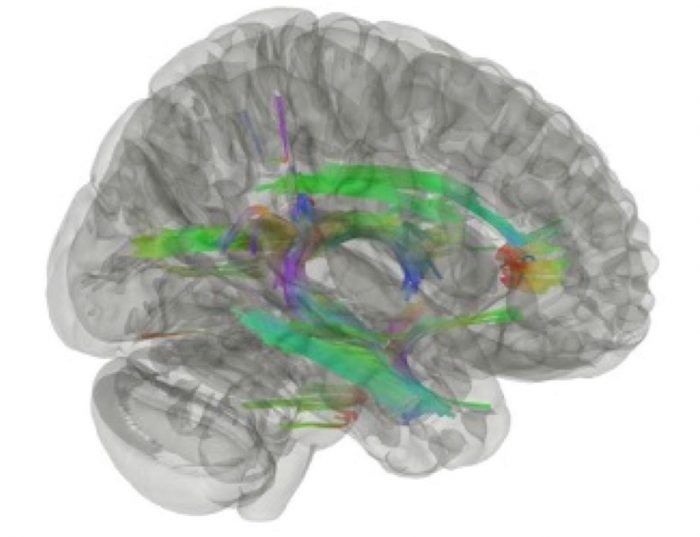

Using a DNA tumor virus that promoted cancer, White discovered that this gene prevented apoptosis, or programmed cell death. After this discovery, which she said she could “see with her own eyes” when she studied the effect of the genes on cells, she asked herself what she’d need to do to push the idea forward for this paradigm shift in thinking about cancer.

As she continued to discover more details about the viral oncogene over the years, she said other researchers discovered that the Bcl-2 human oncogene may function similarly. “I thought, ‘Well, if this is a theme that viral oncogenes and potentially cancer oncogenes are blocking apoptosis, they should be functionally interchangeable,’” White recalled, which is what she showed and published.

She substituted human Bcl2 oncogene of the viral E1B 19K oncogene and showed that they both functioned to block apoptosis interchangeably.

These discoveries, which started at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, among others, helped pave the way for Dr. White’s career, where she is now professor of Molecular Biology and Biochemistry and Deputy Director at the Rutgers Cancer Institute of New Jersey. She is also Associate Director of the Ludwig Princeton Branch of the Ludwig Institute for Cancer Research at Princeton University.

The discovery also led to some anti cancer treatments. Abbott developed the first FDA approved Bcl-2 inhibitor, which others followed.

These kinds of discoveries, which lead to treatments, are why she and others “work so hard, to make a difference for patients,” she said.

Dr. White describes her time at CSHL as an “enormously enriching experience” in which she was surrounded by people who were of “exceptional scientific caliber,” including some who won the Nobel Prize while she was there.

“I had a fertile environment with people that had similar ways of thinking that was very synergistic in terms of propelling the science forward,” she said.

She appreciated the numerous meetings held at CSHL at which she felt like she could learn about anything from the depth and breadth of the material presented and discussed. During these meetings, which she still attends regularly, she has recruited post doctoral researchers to her lab whom she’s met at poster sessions.

As with other alumni of CSHL, Dr. White was particularly pleased with the robust and valuable feedback she and others received. “Critical and productive insights from the scientific community is important to the process of scientific discovery from beginning to the end,” she explained.

White suggested that the layout of the campus and the proximity of so many families created a unique and tight knit community. She recalled how the lab had Santa Claus at Christmas, hay rides to the pumpkin patch and special dinners for people who lived there.

“That very much builds camaraderie and long term friendships and long term relationships,” she said.