The Whaling Museum and Education Center is awarded $5,000 from The Museum Association of New York (MANY) in partnership with the New York State Council on the Arts (NYSCA).

The Museum Association of New York (MANY) in partnership with the New York State Council on the Arts (NYSCA) awarded a total of $500,981 to 102 grantees to assist New York museums with capacity building.

“We thank NYSCA for this partnership and this opportunity to rapidly distribute much-needed funding to New York’s museums,” said Erika Sanger, Executive Director, MANY.

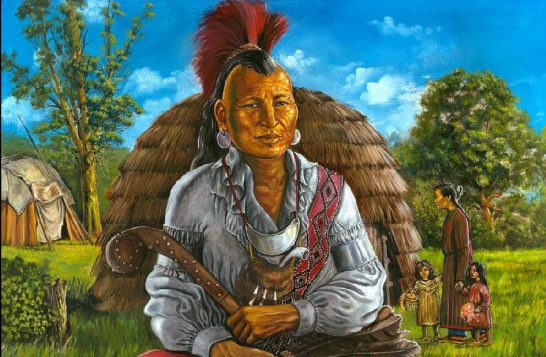

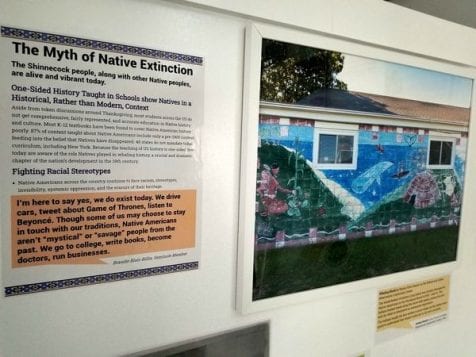

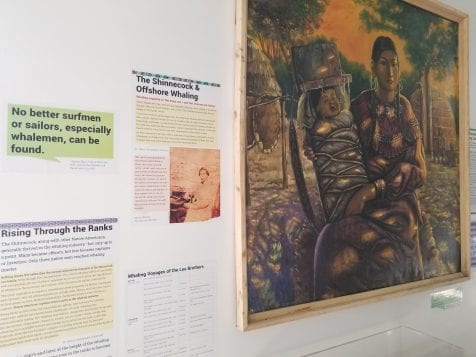

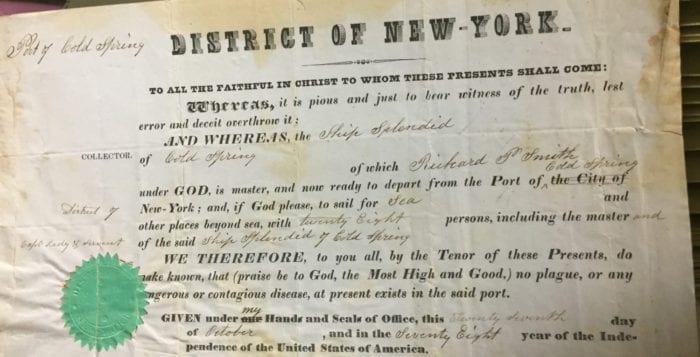

“The wonder of our whaling past continues to capture the public’s imagination. At the same time, many people are unaware of how our country’s maritime industries provided the greatest source of employment to African Americans in the 19th century. There are estimates that between one-quarter and one-third of all American whaling crews were people of color. To illuminate our region’s cultural heritage, we will apply our Partnership Grant Award to strengthen our museum’s commitment to grow engagement through equitable representation in our exhibitions and the stories we share. We are thankful to NYSCA and MANY for choosing to help our museum accomplish this goal for the Long Island community, ” said Nomi Dayan, Executive Director, The Whaling Museum & Education Center.

This grant partnership with NYSCA was developed in direct response to the Institute of Museum and Library Services (IMLS) and Partners for Public Good (PPG) study “Market Analysis and Opportunity Assessment of Museum Capacity Building Programs” report published in March 2021.

Capacity Building grants were awarded in amounts up to and including $5,000 to help museums respond to pandemic-related challenges, build financial stability, strengthen board and community engagement, update technology, support leadership, and change systems to address diversity, equity, access, inclusion, and justice. Awards were made to museums of all budget sizes and disciplines.

The Whaling Museum & Education Center will use the grant funds in advancing the Museum’s capacity to develop, install, and evaluate the special exhibition and public programming project, Black Whalers (working title). The project explores the deep significance of whaling in African American history, a topic largely unknown to the general public. Black Whalers (working title). will benefit lifelong learners by preserving our democratic culture, renewing cultural heritage, deepening cross-cultural understanding, expanding empathy and tolerance, and contributing to strengthened cultural identity by fostering a shared vision for the Long Island community in a post-covid world.

“The arts and culture sector is facing a multi-year recovery process after two years of unimaginable challenges,” said Mara Manus, Executive Director, NYSCA. “We are grateful to MANY for their stewardship of this opportunity that will ensure New York State museums continue to grow and thrive. We send our congratulations to all grantees on their awards.”

Partnership Grants for Capacity Building are made possible by the New York State Council on the Arts with the support of the Office of the Governor and the New York State Legislature.