By Philip Griffith

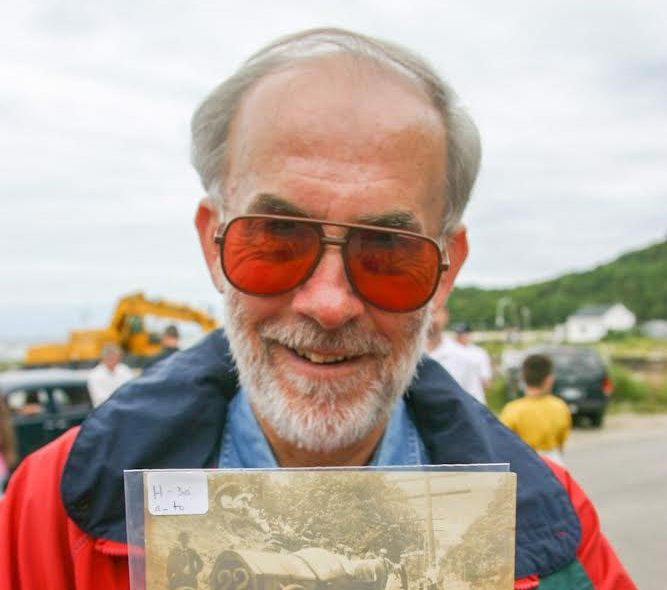

I was sorry to read in The Port Times Record [Oct. 25] that Kenneth C. Brady Jr., born April 17, 1943, passed away on Oct. 24.

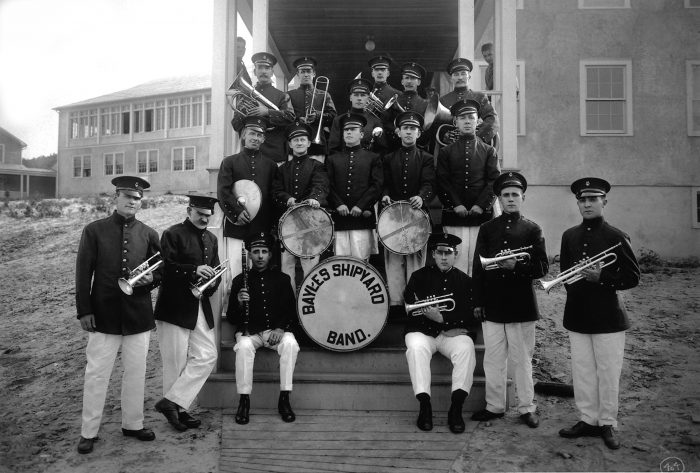

Ken inherited Rob Sisler’s title, Port Jefferson village historian. Brady was the quintessential explorer of our Port history. He leaves us a legacy of 17,500 priceless photographs, numerous articles, eloquent historical lectures, fascinating artifacts and public exhibitions. A wise Irish patron of a local pub advised me, “Always expect the worst. You’ll never be disappointed.”

It was my pleasure to meet Ken as a co-writer and editor of The Echoes of Port newsletter distributed by the Historical Society of Greater Port Jefferson. He taught me much about accurate research and reporting. Along with me, Brady was a founding member of Port Jefferson Conservancy and later became its president. He worked tirelessly to preserve our village history, architecture, parks and surrounding waters of the Long Island Sound.

Beyond Port Jefferson, he served as president of the Suffolk County Historical Society. His books on Belle Terre and photographs of Arthur S. Greene are gems. I especially enjoyed his many photographic exhibits at the Port Jefferson Village Center and at our annual dinner of the Port Jefferson Historical Society at Port Jefferson Country Club.

In addition, Ken was a frequent contributor to The Port Times Record, best known for his Hometown History series. TBR News Media named him as a 2013 People of the Year winner.

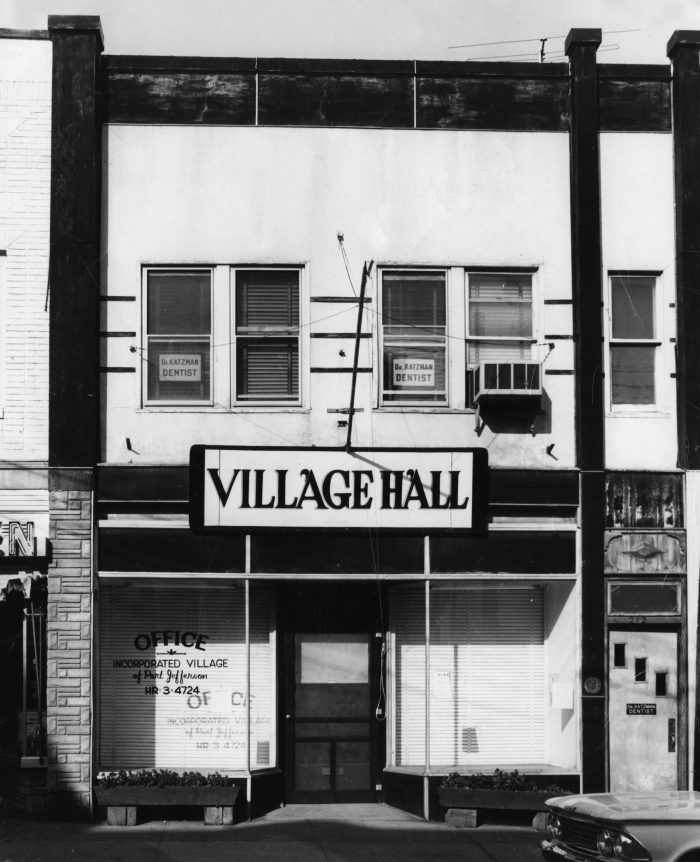

I visited Ken many times in his archive office, which he designed and created on the second floor of the Village Center. He was always gracious about my interrupting his work and generous with sharing information for my research. Ken was a walker and often greeted residents on his journey. My grandson Jack lived on South Street, and Ken always gave him a high five and a smile. When Jack went ice skating at The Rinx adjoining the Village Center, he always went upstairs to visit Ken, who offered him a few peppermint candies to enjoy.

A retired Sachem teacher, Ken loved children and Jack loved him — as all who knew him did.

Ken had a great sense of humor. He was a kind, intelligent, unassuming gentleman. You’d see him in his Montauk sweatshirt, a place where he spent many days at his second home. In this small resort village called “The End,” and the location of seven Stanford White homes, Ken spent many hours with his good friends, Mike and Claire Lee. The surrounding ocean waters beguiled them. Ireland, the land of his ancestors, is noted for its saints and scholars. In my judgment, Ken qualified for both categories.

It is ironic that days before Ken’s death, I met Mike Lee at the Colosseo Pizzeria in Port Jeff Station. As I frequently do, I asked Mike, “How is Ken?” He replied, “Fine.”

There’s an old Hasidic adage that goes, “If you want to make God laugh, tell him your plans for the next week.” At 11 a.m. on Oct. 27 in Cedar Hill Cemetery, Kenneth C. Brady Jr. was laid to rest before more than 100 friends and neighbors. The Methodist Rev. Charles Van Houten conducted the solemn graveside service. Van Houten and attending mourners offered prayers.

Mike Lee made a fittingly concluding remark. I made a fittingly concluding remark, too. I said, “Ken, you are now a part of Port Jefferson’s history.”

Rest in peace.