Hometown History: WWI housing for Port Jefferson’s shipbuilders

Following America’s entry into World War I, the number of employees at the Bayles Shipyard in Port Jefferson jumped from 250 in November 1917 to 1,022 in January 1919.

Since many of these workers could not find housing in the village, the United States Shipping Board campaigned to persuade the area’s homeowners to rent rooms to Port Jefferson’s shipbuilders.

A painting by commercial artist Rolf Armstrong was offered as a prize to the villager who did the most to alleviate the housing shortage. Since this and other efforts did not meet much success, the USSB retained architect Alfred C. Bossom to design cottages and dormitories in Port Jefferson for the burgeoning population.

Bossom recognized the urgent need to provide accommodations for the wartime labor force, his numerous commissions including the Remington Apartments high-rise complex built for workers at the Remington Arms munitions factory in Bridgeport, Connecticut.

To secure a site for Port Jefferson’s housing development, the Bayles Shipyard purchased almost 16 acres of land just west of Barnum Avenue from Catherine Campbell in July 1918.

Nine detached, one-family homes were designed by Bossom to reflect the character of “old Long Island fishing villages” and erected along Cemetery Avenue, later renamed Liberty Avenue.

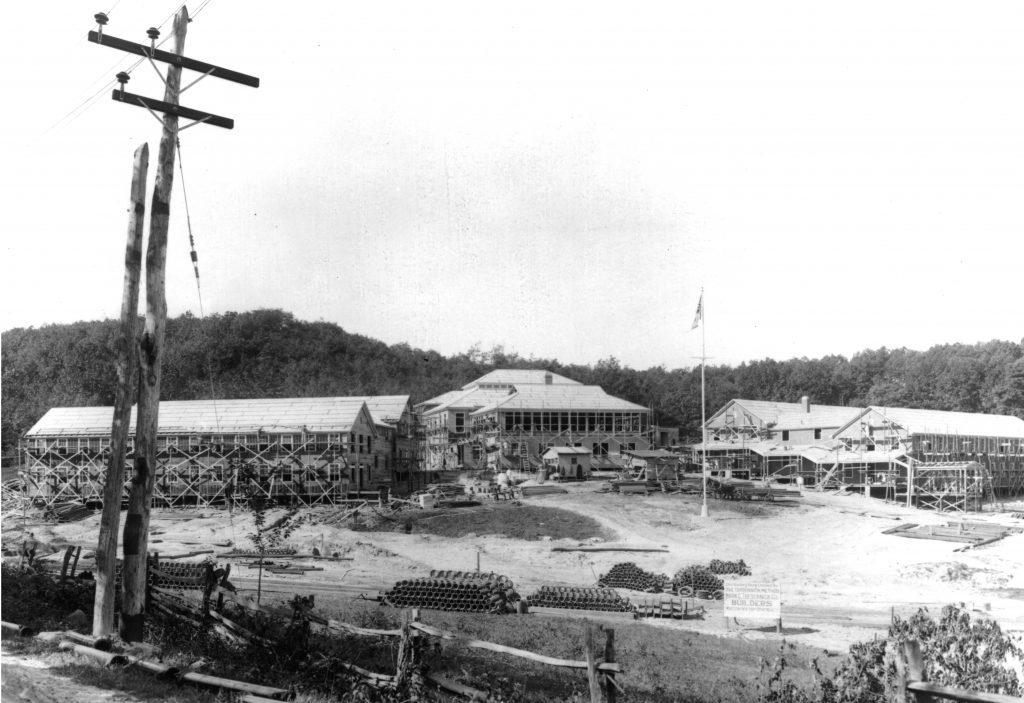

Bossom also designed a dormitory unit called the Plant Hotel since it accommodated employees at the Bayles plant. The Mark C. Tredennick Company, which had constructed buildings at the Army’s Camp Upton in Yaphank, was named the general contractor.

Now the site of Earl L. Vandermeulen High School, the Plant Hotel included 206 rooms, a cafeteria, powerhouse, athletic field and water purification facilities. A porch connected the three major wings of the complex.

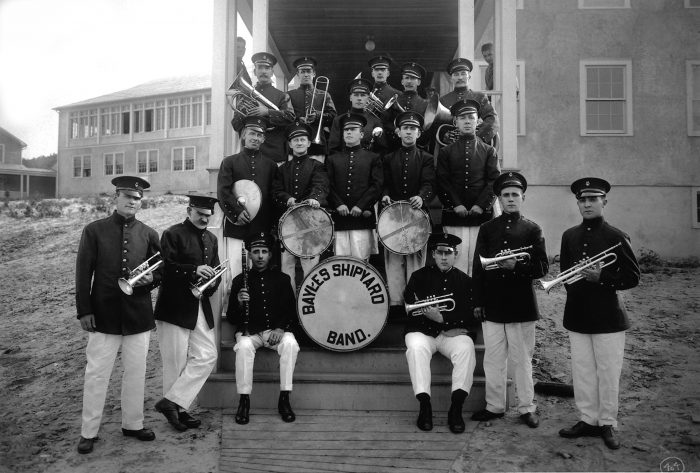

Completed in December 1918 just after the Armistice on Nov. 11, the hotel soon became the center of social life for shipyard workers. A band was formed, a baseball team was organized and dances were held on Friday evenings.

In April 1919, the Emergency Fleet Corporation commandeered the Bayles Shipyard because of the unsatisfactory progress at the facility. The seized property, which included the Plant Hotel, was then sold to the New York Harbor Dry Dock Corporation.

When the new owners fired hundreds of shipyard workers, the number of boarders at the Plant Hotel dropped dramatically. To compensate for this loss, the hotel began offering rooms to transients by the day or week.

The Port Jefferson Times scolded the hotel’s new clientele for destroying electric bulbs, smashing wash basins, spitting on the floors and generally behaving as if they were hoodlums.

In December 1920, the NYHDDC shut down the Bayles Shipyard, dismissing all of its workers except for a skeleton crew. Confronted with a virtually empty Plant Hotel, the NYHDDC leased the complex to the Federal Board for Vocational Education, later renamed the United States Veterans Bureau.

The Plant Hotel, which had been extensively damaged by some departing boarders, was refurbished as a training center charged with teaching disabled soldiers and sailors.

The initial group of 125 veterans arrived at the Plant Hotel in October 1921. During a typical three-month stay, the men prepared for new careers and received medical care. For recreation, they were entertained by theatrical troupes, went on field trips and enjoyed Friday night concerts.

Despite pressure from local business groups and politicians, in June 1923 the Veterans Bureau left Port Jefferson as part of a nationwide plan to consolidate its rehabilitation facilities.

As demobilization continued, local businessman Jacob S. Dreyer purchased the Liberty Avenue cottages, which have changed hands several times over the years and are still standing. In July 1929, taxpayers in the Port Jefferson school district voted to purchase the Plant Hotel itself and the remaining 13 acres.

In subsequent elections, the citizens authorized the board of education to sell some of the hotel’s furnishings, grade the grounds and construct an athletic field on the site. In June 1934, the taxpayers voted to build a high school on the property.

The board of education quickly sold the Plant Hotel to a high bidder for $250. Workers then demolished the building and hauled away the wreckage.

Kenneth Brady has served as the Port Jefferson village historian and president of the Port Jefferson Conservancy, as well as on the boards of the Suffolk County Historical Society, Greater Port Jefferson Arts Council and Port Jefferson Historical Society. He is a longtime resident of Port Jefferson.