By Daniel Dunaief

Thieves come in all shapes and sizes, robbing people of valuable possessions or irreplaceable personal keepsakes.

Diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease and forms of dementia also rob people, taking away their memories, connections to their past and even their sense of themselves.

At times, however, people who are battling these conditions can emerge from its clutches, offering a fleeting, or even longer, connection to the person their loved ones knew, the passions they shared, and the memories that helped define a life.

In a study published in November in the Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease, Stephen Post, Director of the Center for Medical Humanities, Compassionate Care and Bioethics at Stony Brook University, gathered information from surveys with 2,000 caregivers who shared their reactions to unexpected lucidity from forgetful people.

“Caregivers can find inspiration in these fleeting moments,” Post wrote in a summary of the conclusions of the study. “The research aims to guide caregivers and enhance the understanding of the enduring self-identify of deeply forgetful people, promoting compassionate care and recognizing the significance of our shared humanity.”

Such moments of clarity and awareness, at levels that can be more engaging than the typical behaviors for people suffering with various levels of forgetfulness, can be rewarding at any point, but can offer a particular gift to caregivers and families around the holidays.

Possible triggers

Post suggested that these moments of lucidity can be purely spontaneous and surprising. They can also arise during an intervention, when a caregiver or family member provides some specific stimulation or memory trigger.

“Caregivers can sing a song that their loved ones identify with from earlier in life,” said Post. “We’ve done that here at the Long Island State Veterans Home on the Stony Brook campus.”

Several years ago, Post wrote about a room of 50 veterans, many of whom spent a good part of their days in a haze without acting or interacting with others.

When they heard “The Star Spangled Banner” or other patriotic music, as many as 70 percent reacted and started to sing the song. The duration of participation varied, with some saying a few words or a line, others singing a verse, and still others making it through the entire song,

After the song, people who might have seemed out of reach could react to closed-ended questions. This could include choices such as whether they preferred toast or cereal for breakfast.

“A good half of them were able to respond and sometimes even carry on a brief conversation,” Post said.

Art can also help draw out forgetful relatives. Groups around the country are taking forgetful people and their caregivers to art museums in small groups. Looking at a famous or particularly evocative piece of artwork, people might express appreciation for the magnificence of a painting.

Poetry can also serve as a stimulus. Forgetful people who listen to the poems of Robert Frost or other familiar writers can respond with the next line to words deeply ingrained in their memory.

“Their affect picked up,” said Post. “They were smiling, they were excited and enthusiastic. That’s great stuff.”

These moments can provide a connection and offer joy to caregivers.

Other possible triggers include smells, such as the familiar scent of a kitchen; interactions in nature, such as the feel of snow on someone’s face; or playing with pets.

The forgetful can “respond joyfully to dogs,” said Post. “It can remind them of [a particular] dog from 30 years ago.”

Additional research

Caregivers who help forgetful people through their daily lives sometimes struggle with the question of whether “grandma is still there,” Post said. That metaphor, however, can miss the “hints” of continuing self identity.

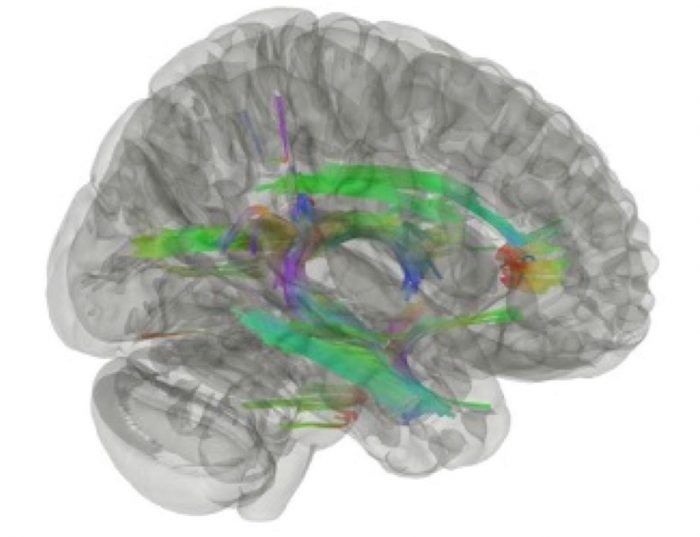

The National Institute on Aging has funded Post’s study on what’s happening with the brain during these moments of lucidity.

A challenge in that research, however, resides in doing PET scans or collecting other data when those moments are spontaneous and unpredictable.

The work from Post’s recent study indicates that these periods of clarity are important for the morale of caregivers, with many of them feeling uplifted from the interaction.

Post sees further opportunity for study. In his next project, he hopes to cover how to operationalize this information into an intervention. “It’s very practical, very real and can do a heck of a lot” for the forgetful and their caregivers, he said.

To be sure, some forgetful people may not respond to some or all of these cues, as the damage from their diseases may have made such outreach and actions inaccessible.

When these moments, fleeting though they may be, occur, they can be rewarding for caregivers, family members and the forgetful themselves.

Photo courtesy of Jean Mueller

Jean Mueller, Assistant Director of Nursing/ Project Manager in the Department of Regulatory Affairs, Patient Safety & Ethics at Stony Brook, recently spent time with her father Daniel, 95. The elder Mueller lost his wife of 74 years Geraldine several weeks ago and is in an assisted living facility.

Taking her father out was too difficult, as it could cause agitation and confusion.

“We went and had Thanksgiving dinner with him there,” Mueller said. “He seemed to really enjoy it, in the moment. He knew the food and he knew it was a holiday. He didn’t ask me where my mom was.”

The interactions can be challenging, as she sometimes feels like she’s pulling “all the strings and you don’t know what you’re going to get” when she interacts with him, she said.

Still, Mueller suggested that it doesn’t matter whether he remembers her visits.

“In the moment, he matters, it matters and he’s still a person,” she said. ‘When you get to the point where everything has been taken away from you, and you lost your independence, even if it’s for a short period of time, you can feel valued again.”

She considers it an honor to be able to share that with her father.

A former inspector in the Suffolk County Police Department and a commander of homicide, Mueller’s father has a well-known sweet tooth.

When she visits, Mueller brings an iced coffee with hazelnut syrup and half and half, a crumb cake, croissant or donut. “He’s in seventh heaven,” she said.

When he sees his family, his face “lights up,” said Mueller.

“Even if the memories of our visit is fleeting, for those moments in time, he’s a devoted father and a valued father and grandfather who still feels our love.”