By Daniel Dunaief

Captivity causes changes in a brain, at least in the shrew.

Small animals that look like rodents but are related to moles and hedgehogs, shrews have different gene expression in several important areas of their brain during captivity.

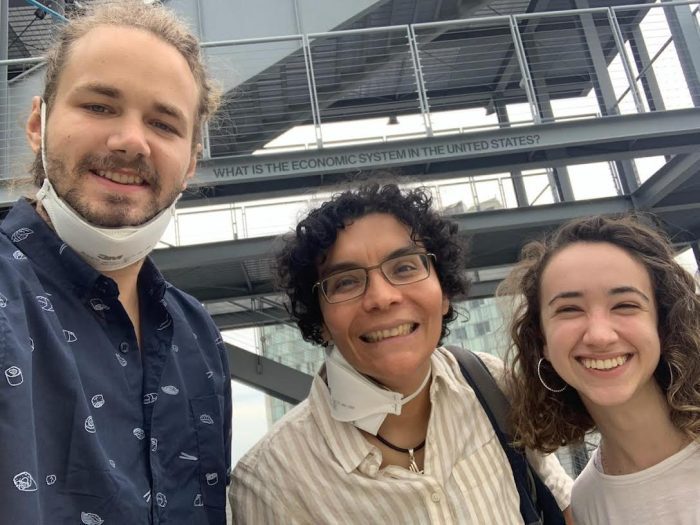

In a study led by 2022 Hearst summer Undergraduate Research Fellow Maria Alejandra Bedoya Duque in the lab of Stony Brook Professor Liliana Dávalos, shrews in captivity had different gene expression in the cortex, hippocampus and olfactory bulb. These brain areas are important for cognition, memory and environmental sensing.

“I was very surprised by what we found,” said Dávalos. While she expected that the research might uncover differences between the brains of captive and wild animals, she didn’t expect the changes to be as many or as strong.

The change in brain activity could offer potential alternative explanations for studies that explore the effect of various experiments on animals kept in captivity.

“It could be very useful to find out if these environmental influences could be confounding,” said Dávalos. “We don’t know all the dimensions of what captivity is doing.”

Additionally, brain activity changes in captivity for shrews in terms of the transcripts that are over or under expressed mirror those found in humans who have neurological changes such as major depressive disorder or neuro degenerative disorders.

“How these [changes] influence behavior or cognition is a separate question,” Dávalos added.

To be sure, extrapolating from shrews to humans is different and requires careful analysis, Dávalos explained.

Humans and shrews have distinct life history, ecology, body size and other characteristics. While scientists can study genes they think might have similar functions, more studies are necessary to determine the effects of those genes in expression and how similar they are to those studied in humans or mice.

Dávalos does not expect to find a silver bullet that reorganizes human brains or a gene or pathway that’s going to revolutionize neurodegenerative research.

Nonetheless, in and of itself, the study suggested opportunities for further research and exploration into the effects of captivity on animals in general and, in particular, on their mental processes, which are affected by changes in conditions and needs in their environment.

A foundation for future work

The study, which was recently published in the journal Biology Letters, grew out of a two-month internship Bedoya did at Stony Brook in which she studied the brains of four captive shrews and four wild animals. The analysis of the results involved numerous calls and discussions when she returned to Colombia to finish her undergraduate degree.

At the end of the summer, Bedoya was “going to present her work internally at Stony Brook,” explained William Thomas, a postdoctoral researcher in Dávalos’s lab and one of Bedoya’s mentors throughout the project. “Instead, she turned it into a paper.”

Thomas appreciated how Bedoya “put in a lot of work to make sure she got this out,” he said.

The shrew’s brain changed after two months in captivity, which is about 20 percent of their total lifespan, as shrews live an average of one year.

“We don’t know what the limits are,” in terms of the effect of timing on triggering changes in the shrew’s brain, Thomas said. “We don’t know how early the captive effect is.”

Thomas suggested that this paper could “lay the foundation for future studies with larger samples.”

Dávalos was pleased that the study resulted in a meaningful paper after a summer of gathering data and several years of analyzing and presenting the information.

“I’m immensely proud and happy that we had this unexpected finding,” said Dávalos. “It is one of the most gratifying experiences as a mentor.”

A launching pad

Bedoya, who graduated from Universidad Icesi in 2023 and is applying to graduate school after working as an adjunct professor/ lecturer at her alma mater, is pleased her work led to a published paper.

“I was so happy,” said Bedoya. “If it hadn’t been for [Thomas] and [Dávalos] cheering me on the whole time when I came back to Colombia, this study could have ended as my fellowship ended.”

Bedoya believes the experience at Stony Brook provided a launching pad for her career.

“It is a very valuable experience to have conducted this research all the way up to publication,” she said.

Thomas and Dávalos each recalled their own first scientific publication.

“I’m happy and relieved when they come out,” said Thomas. “While internal validation is important, the pleasure comes from providing something that you believe can help society.”

Dávalos’s first publication involved some unusual twists and turns. When she submitted her first paper about deforestation in the Andes, the journal wrote back to her in a letter telling her the paper was too newsy. She submitted it to several other publications, including one that indicated they had a huge backlog and weren’t publishing new research.

When it was published, the paper didn’t receive much attention. That paper, and another on her thoughts about how peace between the Colombian government and the FARC rebels might be worse for the rainforest, have since been cited frequently by other researchers.

Winter brain

At around the same time that Bedoya published her work about the effect of captivity on the shrew brain, Thomas published a study in the journal eLife in which he examined how shrew brains shrank during the winter and then regrew during the spring.

This work could offer genetic clues to neurological and metabolic health in mammals. Thomas focused on the hypothalamus, measuring how gene expression shifts seasonally.

A suite of genes that change across the seasons were involved in the regulation of energy homeostasis as well as genes that regulate cell death that might be associated with reductions in brain size.

Temperature was the driver of these seasonal changes.

The genes involved in maintaining the blood brain barrier and calcium signaling were upregulated in the shrew compared with other mammals.

After the winter, the shrew’s brains recovered their size, although below their pre-winter size.

Originally from Syracuse, Thomas attended SUNY Albany.

When he was younger, he entertained ideas of becoming a doctor, particularly as his grandmother battled ALS. On his first day shadowing a physician, he felt claustrophobic in the exam room and almost passed out.

He wanted to be outside instead of in “the squeaky clean floors” of a doctor’s office, he explained in an email.

As a scientist, he feels he can meld his passion for nature and his desire to help those who suffer from disease.

Teddy Roosevelt had numerous pets when he was president, including snakes, dogs, cats, a badger, birds, and guinea pigs.

Teddy Roosevelt had numerous pets when he was president, including snakes, dogs, cats, a badger, birds, and guinea pigs.