By Daniel Dunaief

What better day than today, March 14, to celebrate numbers? In case you haven’t heard, math teachers around the country have been getting in on the calendar action for 31 years, designating the day before Caesar’s dreaded Ides of March as pi day, because the first three numbers of this month and day — 3, 1, 4 — are the same as pi, the Greek letter that is a mathematical constant and makes calculations like the area and circumference of a circle possible.

We can become numb to numbers, but they are everywhere and help define and shape even the non-perfectly circular parts of our lives.

We have a social security number, a birth date, a birth order, height and weight, and a street address, with a latitude and longitude, if we’re especially numerically inclined.

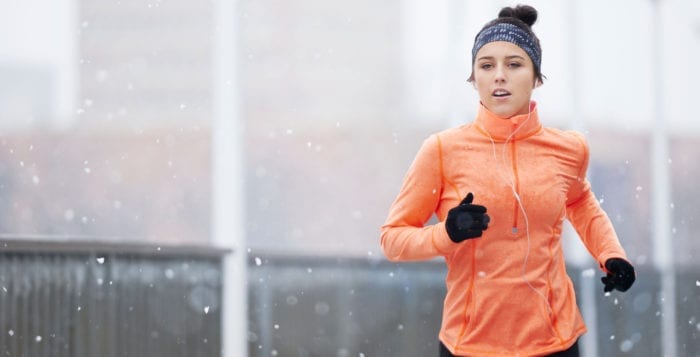

Numbers save us, as computer codes using numbers keep planes from flying at the same altitude. Numbers tell us what to wear, as the temperature, especially around this time of year, dictates whether we take a sweatshirt, jacket or heavy coat.

We use them when we’re ordering food, paying for a meal in a restaurant and counting calories. They are a part of music as they dictate rhythms and tempos, and of history, allowing us to keep the order of events straight.

We use numbers to keep track of landmarks, like the year of our graduation from high school or college, the year we met or married our partners, or the years our children were born.

Numbers help us track the time of year. Even a warm day in February doesn’t make it July, just as a cold day in June doesn’t turn the calendar to November.

Numbers help us track the time of year. Even a warm day in February doesn’t make it July, just as a cold day in June doesn’t turn the calendar to November.

People complain regularly that they aren’t good at math or science, and yet they can calculate the time it takes to get to school to pick up their kids, get them home to do their homework, cook dinner and manage a budget, all of which requires an awareness of the numbers that populate our lives.

We know when to get up because of the numbers flashing on the phone or alarm clock near the side of our bed, which are unfortunately an hour, 60 minutes or 3,600 seconds ahead thanks to daylight savings time. Many of our numbers are in base 10, but not all, as our 24-hour clocks, 24-hour days, 12-month years and seven-day weeks celebrate other calculations.

Numbers start early in our lives, as parents share their children’s height and weight and, if they’re preparing themselves for a lifetime of monitoring their children’s achievements, their Apgar scores.

Children read Dr. Seuss’ “One Fish, Two Fish, Red Fish, Blue Fish.” We use numbers to connect the dots in a game, drawing lines that form an image of Dumbo or a giraffe.

Numbers progress through our elementary education — “I’m 10 and I’m in fifth grade” — and they follow us in all of our activities: “I got a 94 on my social studies test.”

Imagine life without numbers, just for 60 seconds or so. Would everything be relative? How would we track winners and losers in anything, from the biggest house to the best basketball team? Would we understand how warm or cold the day had become by developing a sliding scale system? Would we have enough ways to capture the difference between 58 degrees Fahrenheit and 71 degrees?

Objects that appear uncountable cause confusion or awe. Look in the sky and try to count the stars, or study a jar of M&Ms and try to calculate the number of candies.

A picture may be worth a thousand words, but a number tells its own tale — it was a six-alarm fire, I had 37 friends at my birthday party or I walked a mile in a circle, which means the diameter of that circle was about 1,680 feet — thanks to pi.