By Daniel Dunaief

Two letters defined the DNA Learning Center at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory over the last several months: re, as in rethink, reimagine, reinvent, recreate, and redevelop. They also start the word reagent, which are chemicals involved in experiments.

The 32-year-old Learning Center, which teaches students from fifth grade through undergraduates, as well as teachers from elementary school to college faculty, shared lessons and information from a distance.

At the Learning Center, students typically benefit from equipment they may not have in their schools. That has also extended to summer camps. “Our camps are built on this experiential learning,” said Amanda McBrien, an Assistant Director at the Learning Center.

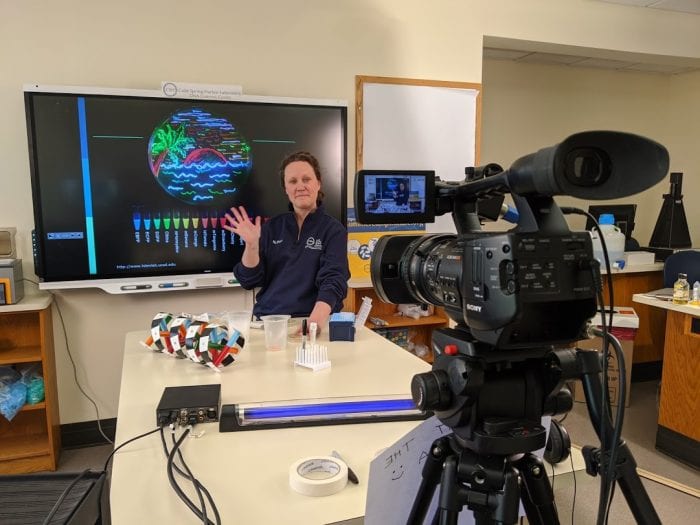

While that part of the teaching experience is missing, the center adapted to the remote model, shifting to a video based lessons and demonstrations. Indeed, campers this year could choose between a live-streamed and an on-demand versions.

Dave Micklos, the founder of the Learning Center, was pleased with his staff’s all-out response to the crisis.

“The volume of new videos that we posted on YouTube was more than any other science center or natural history museum that we looked up,” Micklos said. “It takes a lot of effort to post content if you’re doing it in a rigorous way.” During the first few months of the lockdown, the Learning Center was posting about three or four new videos each day, with most of them produced from staff members’ homes.

As for the camps, the Learning Center sent reagents, which are safe and easy to use, to the homes of students, who performed labs alongside instructors. In some camps, students isolated DNA from their own cells, plant or animal cells and returned the genetic samples to the lab. They can watch the processing use the DNA data for explorations of biodiversity, ancestry and detecting genetically modified organisms.

The Learning Center has been running six different labs this summer.

The virtual camps allowed the Learning Center to find a “silver lining from a bad situation” in which students couldn’t come to the site, McBrien said. The Learning Center developed hands-on programs that they sent throughout the country.

McBrien said the instructors watched each other’s live videos, often providing support and positive feedback. Some people even watched from much greater distances. “We had a few regulars who were hysterical,” McBrien said. “One guy from Germany, his name is Frank, he was in all the chats. He loved everything we did” and encouraged the teachers to add more scientific lessons for adults.

McBrien praised the team who helped “redevelop a few protocols” so high-level camps could enable students to interact with instructors from home.

Using the right camera angles and the equipment at the lab, the instructors could demonstrate techniques and explain concepts in the same way they would in a live classroom setting. To keep the interest of the campers, instructors added polls, quizzes and contests. Some classes included leader boards, in which students could see who answered the most questions correctly.

This summer, Micklos and Bruce Nash, who is an Assistant Director at the Learning Center, are running a citizen science project, in which teams from around the country are trying to identify ants genetically throughout the United States.

Using a small kit, one reagent and no additional equipment, contributing members of the public, whom the Learning Center dubs “Citizen Scientists,” are isolating DNA from about 500 of the 800 to 900 species of ants.

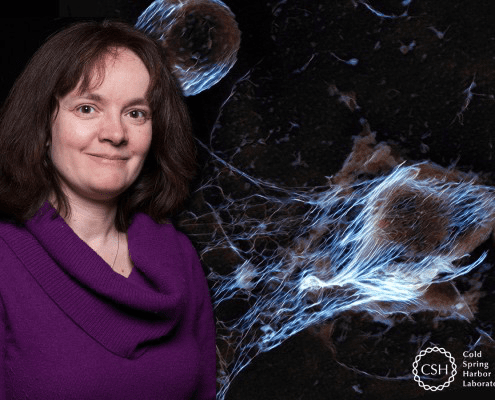

In one of the higher level classes called metabarcoding or environmental DNA research, teachers collected microbes in a sample swabbed from their nose, their knees, tap water, and water collected from lakes.

The Learning Center supports this effort for high school research through Barcode Long Island, which is a partnership with the Hudson River Park to study fish in the Hudson. High school interns and the public help with sampling and molecular biology.

“Much like barcoding, we aim to democratize metabarcoding,” Nash explained in an email. A metabarcoding workshop that ended recently had participants in Nigeria, Canada, Antigua and distant parts of the United States, with applicants from Asia.

After teaching college faculty on bar coding, Micklos surveyed the teachers to gauge their preference for future courses, assuming in-person meetings will be possible before too long.

When asked if they would like in-person instruction only, a hybrid model, or classes that are exclusively virtual, none of the teachers preferred to have the course exclusively in person. “People are beginning to realize it is more time efficient to do things virtually,” Micklos said.

Nash added that the preference for remote learning predated the pandemic.

Micklos appreciates the Learning Center’s educational contribution. “To pull these things off with basically people talking to each other via computer, to me, is pretty amazing,” he said.

Around four out of 10 students who enter college who have an interest in pursuing careers in science continue on their scientific path. That number, however, increases to six out of 10, when the students have a compelling lab class during their freshman year, Micklos said.

Lab efforts such as at the Learning Center may help steady those numbers, particularly during the disruption caused by the pandemic.

The longer-term goal at the Learning Center, Micklos said, is to democratize molecular biology with educational programs that can be done in the Congo, the Amazon or in other areas.

As for the fall, the leadership at the center plans to remain nimble.

The Learning Center is planning Virtual Lab field trips and will also continue to offer “Endless Summer” camp programs for kids and parents looking for science enrichment.

The Center also hopes to send instructors for in-person demonstrations at schools, where they can host small groups of student on site.

“We are supporting as many people as possible through our grant-funded programs and our (virtual) versions of camps and field trips,” Nash said. “These will be adapted to support schools and others to progressively improve them through the fall, with the hope of reaching all those we would normally reach.”