By Daniel Dunaief

It’s a catch-22: some promising scientific projects can’t get national funding without enough data, but the projects can’t get data without funding.

That’s where private efforts like The Mark Foundation for Cancer Research come in, providing coveted funding for promising high-risk, high-reward ideas. Founded and funded by Pamplona Capital Management CEO Alex Knaster in 2017, the Foundation has provided over $117 million in grants for various cancer research efforts.

This year, The Mark Foundation, which was named after Knaster’s father Mark who died in 2014 after contracting kidney cancer, has provided inaugural multi-million dollar grants through the Endeavor Awards, which were granted to three institutions that bring scientists with different backgrounds together to address questions in cancer research.

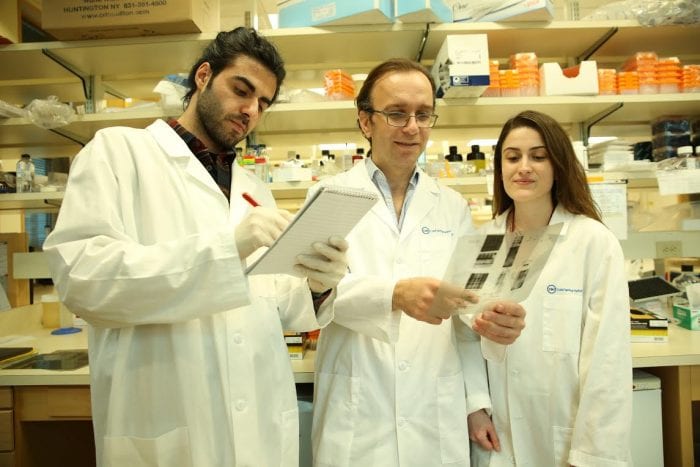

In addition to teams from the University of California at San Francisco and a multi-lab effort from Columbia University, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center and Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory scientists Tobias Janowitz and Semir Beyaz received this award.

“We are absolutely delighted,” Janowitz wrote in an email. “It is a great honor and we are excited about the work.” He also indicated that the tandem has started the first set of experiments, which have produced “interesting results.”

The award provides $2.5 million for three years and, according to Janowitz, the researchers would use the funds to hire staff and to pay for their experimental work.

Having earned an MD and a PhD, Janowitz takes a whole body approach to cancer. He would like to address how the body’s response to a tumor can be used to improve treatment for patients. He explores such issues as how tumors interact with the biology of the host.

Semir Beyaz, who explores how environmental factors like nutrients affect gene expression, metabolic programs and immune responses to cancer, was grateful for the support of the Mark Foundation.

Beyaz initially spoke with the foundation about potential funding several months before Janowitz arrived at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory. When the researchers, whose labs are next door to each other, teamed up, they put together a multi-disciplinary proposal.

“If the risks [of the proposals] can be mitigated by the innovation, it may yield important resources or new paradigms that can be incorporated into research proposals that can be funded by the [National Institutes of Health] and other government agencies,” Beyaz said.

Janowitz wrote that he had a lunch together in a small group with Knaster, who highlighted the importance of “high-quality data and high-quality data analysis to advance care for patients with cancer.”

Michele Cleary, the CEO of The Mark Foundation, explained that the first year of the Endeavor program didn’t involve the typical competitive process, but, rather came from the Foundation’s knowledge of the research efforts at the award-winning institutions.

“We wanted to fund this concept of not just studying cancer at the level of the tumor or tumor cells themselves, but also studying the interaction of the host or patient and their [interactions] with cancer,” Cleary said. “We thought this was a fantastic project.”

With five people on the Scientific Advisory Committee who have PhDs at the Foundation, the group felt confident in its ability to assess the value of each scientific plan.

Scientists around the world have taken an effective reductionistic approach to cancer, exploring metabolism, neuroendocrinology and the microbiome. The appeal of the CSHL effort came from its effort to explore how having cancer changes the status of bacteria in the gut, as well as the interplay between cancer and the host that affects the course of the disease.

These are “reasonable concepts to pursue, [but] someone has to start somewhere,” Cleary said. “Getting funding to dive in, and launch into it, is hard to do if you can’t tell a story that’s based on a mountain of preliminary data.”

Beyaz said pulling together all the information from different fields requires coordinating with computational scientists at CSHL and other institutions to develop the necessary analytical frameworks and models. This includes Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Fellow Hannah Meyer and Associate Professor Jesse Gillis.

“This is not a simple task,” Beyaz said. The researchers will “collaborate with computational scientists to engage currently available state-of-the-art tools to perform data integration and analysis and develop models [and] come up with new ways of handling this multi-dimensional data.”

Cleary is confident Janowitz and Beyaz will develop novel and unexpected insights about the science. “We’ll allow these researchers to take what they learn in the lab and go into the human system and explore it,” she said.

The researchers will start with animal models of the disease and will progress into studies of patients with cancer. The ongoing collaboration between CSHL and Northwell Health gives the scientists access to samples from patients.

With the Endeavor award, smaller teams of scientists can graduate to become Mark Foundation Centers in the future. The goal for the research the Foundation funds is to move towards the clinic. “We are trying to join some dots between seemingly distinct, but heavily interconnected, fields,” Beyaz said.

Beyaz has research experience with several cancers, including colorectal cancer, while Janowitz has studied colorectal and pancreatic cancer. The tandem will start with those cancers, but they anticipate that they will “apply similar kinds of experimental pipelines” to other cancer types, such as renal, liver and endometrial, to define the shared mechanisms of cancer and how it reprograms and takes hostage the whole body, Beyaz said.

“It’s important to understand what are the common denominators of cancer, so you might hopefully find the Achilles Heel of that process.”

While Cleary takes personal satisfaction at seeing some of the funding go to CSHL, where she and Mark Foundation Senior Scientific Director Becky Bish conducted their graduate research, she said she and the scientific team at the foundation were passionate to support projects that investigated the science of the patient.

“No one has tried to see what is the cross-talk between the disease and the host and how does that actually play out in looking at cancer,” said Cleary, who earned her PhD from Stony Brook University. “It’s a bonus that an institution that [she has] the utmost respect for was doing something in the same space we cared” to support.

The CSHL research will contribute to an understanding of cachexia, when people with cancer lose muscle mass, weight, and their appetite. Introducing additional nutrition to people with this condition doesn’t help them gain weight or restore their appetite.

Janowitz and Beyaz will explore what happens to the body physiologically when the patient has cachexia, which can “help us understand where we can intervene before it’s too late,” Cleary said.

The CSHL scientists will also study the interaction between the tumor and the immune system. Initially, the immune system recognizes the tumor as foreign. Over time, however, the immune system becomes exhausted.

Researchers believe there might be a “tipping point” in which the immune system transitions from being active to becoming overwhelmed, Cleary said. People “don’t understand where [the tipping point] occurs, but if we can figure it out, we can figure out where to intervene.”

Scientists interested in applying for the award for next year can find information at the web site: https://themarkfoundation.org/endeavor/. Researchers can receive up to $1 million per year for three years. The Mark Foundation is currently considering launching an Endeavor call for proposals every other year.