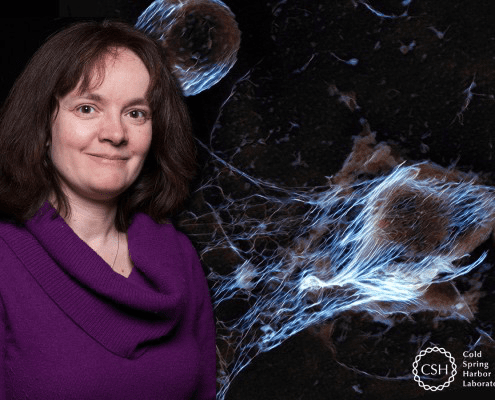

CSHL’s Mikala Egeblad takes novel COVID-19 approach

By Daniel Dunaief

Mikala Egeblad couldn’t shake the feeling that the work she was doing with cancer might somehow have a link to coronavirus.

Egeblad, who is an Associate Professor and cancer biologist at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, recently saw ways to apply her expertise to the fight against the global pandemic.

She studies something called neutrophil extracellular traps, which are spider webs that develop when a part of the immune system triggered by neutrophil is trying to fight off a bacteria. When these NETs, as they are known, are abundant enough in the blood stream, they may contribute to the spread of cancers to other organs and may also cause blood clots, which are also a symptom of more severe versions of COVID-19, the disease caused by the coronavirus, which has now infected over two million people worldwide.

“I always felt an urgency about cancer, but this has an urgency on steroids,” Egeblad said.

Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory reached out to numerous other scientists who specialize in the study of NETs, sometimes picking up on the tweets of colleagues who wondered in the social networking world whether NETs could contribute or exacerbate the progression of Covid19.

Egeblad started by reaching out to two scientists who tweeted, “Nothing about NETs and Covid-19?” She then started reaching out to other researchers.

“A lot of us had come to this conclusion independently,” she said. “Being able to talk together validated that this was something worth studying as a group.”

Indeed, the group, which Egeblad is leading and includes scientists at the Feinstein Institutes for Medical Research and the Research Institute of the McGill University Health Centre, published a paper last week in the Journal of Experimental Medicine, in which they proposed a potential role for NETs.

“We are putting this out so the field doesn’t overlook NETs,” said Egeblad, who appreciated the support from Andrew Whiteley, who is the Vice President of Business Development and Technology Transfer at CSHL.

With a range of responses to the coronavirus infection, from people who have it but are asymptomatic all the way to those who are battling for their survival in the intensive care units of hospitals around the world, the biologist said the disease may involve vastly different levels of NETs. “The hypothesis is that in mild or asymptomatic cases, the NETs probably play little if any role,” she said.

In more severe cases, Egeblad and her colleagues would like to determine if NETs contribute or exacerbate the condition. If they do, the NETs could become a diagnostic tool or a target for therapies.

At this point, the researchers in this field have ways of measuring the NETs, but haven’t been able to do so through clinical grade assays. “That has to be developed,” Egeblad explained. “As a group, we are looking into whether the NETs could come up before or after symptoms and whether the symptoms would track” with their presence, she added.

To conduct the lab work at Cold Spring Harbor, Egeblad said her team is preparing to develop special procedures to handle blood samples that contain the virus.

As the lead investigator on this project, Egeblad said she is organizing weekly conference calls and writing up the summaries of those discussions. She and the first author on the paper Betsy J. Barnes, who is a Professor at the Feinstein Institute, wrote much of the text for the paper. Some specific paragraphs were written by experts in those areas.

At this point, doctors are conducting clinical trials with drugs that would also likely limit NET formation. In the specific sub field of working with this immune-system related challenge, researchers haven’t found a drug that specifically targets these NETs.

If the study of patient samples indicates that NETs play an important role in the progression of the disease, particularly among the most severe cases, the scientists will look for drugs that have been tried in humans and are already approved for other diseases. This would create the shortest path for clinical use.

Suppressing NETs might require careful management of potential bacterial infections. Egeblad suggested any bacterial invaders might be manageable with other antibiotics.

NETs forming in airways may make it easier to get bacterial infections because the bacteria likes to grow on the DNA.

Thus far, laboratory research studies on NETs in COVID-19 patients have involved taking samples from routine care that have been discarded from their daily routine analysis. While those are not as reliable as samples taken specifically for an analysis of the presence of these specific markers, researchers don’t want to burden a hospital system already stretched thin with a deluge of sick patients to provide samples for a hypothetical pathway.

Egeblad and her colleagues anticipate the NETs will likely be more prevalent among the sicker patients. As more information comes in, the researchers also hope to link comorbidities, or other medical conditions, to the severity of COVID-19, which may implicate specific mechanisms in the progression of the disease.

“There are so many different efforts” to understand what might cause the progression of the disease, Egeblad said. “Everybody’s attention is laser focused.” A measure that is easy to study, such as this hypothesis, could have an impact and “it wouldn’t take long to find out,” she added. Indeed, she expects the results of this analysis should be available within a matter of weeks.

Egeblad believes the NETs may drive mucus production in the lungs, which could make it harder to ventilate in severe cases. They also may activate platelets, which are part of the clotting process. If they did play such a role, they could contribute to the blood clotting some patients with coronavirus experience.

Egeblad recognizes that NETs, which she has been studying in the context of cancer, may not be involved in COVID-19, which researchers should know soon. “We need to know whether this is important.”