Four Harbors Audubon Society will present a summer lecture titled “Osprey 2019: The Revival of a Global Raptor” at Avalon Park and Preserve’s Barn on Shep Jones Lane in Stony Brook on Saturday, July 13 at 6:30 p.m. Guest speaker Alan F. Poole, who has been studying ospreys for over 35 years, will speak about the extraordinary resurgence in osprey numbers globally and bring participants up-to-date on the current state of one of our best-loved birds of prey. Free and open to all. Reservations are required by emailing [email protected].

Old Field Farm hosts annual horse show

The Suffolk Classic Horse Show was held July 7 at Old Field Farm county parklands located at 92 W. Meadow Road in East Setauket. The historic Long Island show grounds were built by philanthropist Ward Melville in 1931.

Both adult and children equestrians competed in numerous categories, and results can be found at www.horseshowing.com.

Editorial: After July Fourth, put your fireworks away

The showers of sparks that rained down on our heads the night of Fourth of July were inspiring — grandiose and touching all at once. Fireworks and Independence Day go together like old friends, a tradition that touches the heart. Long Island is home to many of these shows, from the Bald Hill spectacle to the fireworks set off on the West Beach in Port Jefferson.

Then there are the smaller shows, the ones put on by the local neighborhoods in the cool of night. While the grand displays of the professional shows are like standing in the majesty under the lights of Times Square, the small community shows are more like candles set along the mantle in a dark room. Both can be spectacular in their own ways.

Though of course, one is done by amateurs, often in illegal circumstances. And even after the festivities, fireworks continue to light up the sky despite its danger and how it may impact the surrounding community.

Unlike other New York counties, Suffolk County has bans on sparklers, along with firecrackers, bottle rockets, Roman candles, spinners and aerial devices. The Suffolk County Fire Marshals beg people to put down their own fireworks and attend one of the professionally manned shows.

And it seems they have had good reasons, both past and present, to press people for caution. Two women from Port Jefferson Station were injured with fireworks the night of July Fourth when one ended up in their backyard. While other media outlets reported only light injuries, in fact their injuries were much more severe, and readers will read that story in the coming week’s issue.

But of course, the injuries don’t just happen here on the North Shore. A 2018 report from the U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission shows that in 2017, fireworks were involved in an estimated 12,900 injuries. Children under the age of 15 accounted for 36 percent of these injuries. Sparklers accounted for an estimated 1,200 emergency department-treated injuries.

And it’s not over yet. Even a week after July Fourth, fireworks continue to go up with sparks and bangs in the din of night.

Residents know to handle their pets scared by the booms of fireworks on Independence Day, but should they have to cower with their pets for days and days afterward?

And of course, that’s not even to mention U.S. veterans, many of whom know what they must do to stay safe if they are suffering from PTSD on July Fourth, but should they have to sequester themselves every day afterward for a week or more?

Sending up fireworks after July Fourth is inconsiderate, to say the least. We at TBR News Media beg people with excess fireworks to put them in packages or put them aside.

And next time July Fourth comes around, we urge caution when using these explosives. Nobody should have to find refuge from their neighbors on the day of the birth of this nation.

D. None of the Above: Searching for perspective after a crummy softball game

When I was younger, I was the best baseball player who ever lived. OK, maybe that’s a wee bit of an exaggeration. Maybe I was a decent player who had a few good games, surrounded by periods of agonizing ineffectiveness, miserable failure and frustrating inadequacies.

Baseball, as its numerous fans will suggest regularly, is a game of failure. And yet those exquisite moments of success — when we break up a no-hitter, get to a ball that seemed destined for open grass or develop the speed to outrun the laser throw from the outfield — make us feel as if we can do anything.

Recently, I have found myself frustrated beyond the normal measure of perspective because I feel as if I’ve lost a step or six when I play softball. My current athletic deficiencies seem to be a harsh reminder of the inexorable journey through time.

As I return from the game in the car, I sometimes bark questions at myself, wondering how I missed an easy pop-up, or how I lunged for yet another pitch I should have hit. My family, who comes to the games to support me, watches me dissolve into a puddle of self-loathing.

Yes, I know, it’s not my finest hours as a parent and I know I’m setting a terrible example. And yet something inside of me, which is both young and old, can’t control the frustration. I’m an older version of the kid who was so annoyed with his own deficiencies that he kicked a basketball over some trees. OK, maybe they were hedges and I probably threw the ball, but in my memory the offending orb traveled a great distance.

So, what was and sometimes is missing from my life that caused these games to be so important? Other than talent, conditioning, plenty of sleep and a commitment to practicing, my biggest problem was, and sometimes still is, a lack of perspective.

People suffer through much greater hardships than a decline in limited athletic skills. Life is filled with challenges and inspiration. People overcome insurmountable odds, push themselves far beyond any expectations by taking small steps for mankind or even small steps for themselves when they weren’t expected to walk at all.

As I know, I am fortunate in many ways to have the opportunity and time to play softball at all. To be sure, I recognize that perspective isn’t what people generally need when they care about something large or small: They need focus. Artists spending countless hours painting, writing, revising, editing or reshooting a scene for a movie to enable the reality of their art to catch up to their vision or imagination often lose themselves in their efforts, forgetting to eat, to call their parents or siblings, to sleep or to take care of other basic needs.

Considerable perspective could prevent them from finding another gear or producing their best work.

And yet perspective, particularly in a moment like a softball game, can soothe the escalated competitor and give the father driving a car with his supportive family a chance to appreciate the people around him and laugh about his inadequacies, rather than dwell on them.

In a movie, perspective often comes from a camera that climbs high into the sky or from someone looking through a window at his children playing in a yard or at a picture of his family in a rickety rowboat. Perhaps if we find ourselves tumbling down the staircase of anger, frustration or resentment, we can imagine handrails we can grab that allow us to appreciate what we have and that offer another way of reacting to life.

Between You and Me: Women’s soccer winners level the playing field

By Leah S. Dunaief

Last week a theme in this column was a defense of men. In a neat turnabout, this week is a shoutout for women. The catalyst, of course, is the victory of the United States women’s soccer team. We all watched or cheered Sunday as they defeated the Netherlands team, 2-0, to win the four-yearly Women’s World Cup championship in France. And we all felt tremendous pride in their accomplishment on behalf of our nation.

Let’s face it. They won because they had to win. They became symbols of issues larger than themselves, and in order to drive home those issues most effectively, they had to be winners. You might even say they leveled the playing field in multiple ways.

In becoming winners, they achieved a record four championships for the United States since the tournament began in 1991, this while the men’s counterpart fell later that day in the 2019 CONCACAF Gold Cup final to the rival Mexico team, 1-0, in Chicago. The fact that the most visible and outspoken women’s team member, Megan Rapinoe, who was named most valuable player and who also won the Golden Boot for being the highest scorer, was repeatedly identified as a lesbian, gave her the additional burden of championing the rights of marginalized communities. And the swelling chorus of “Equal pay! Equal pay!” from the spectators at the end of the match was a victory for social justice that brought tears to my eyes and similarly affected many other women in the workplace.

In 1963, when I was interviewing for a position with Time Inc. in New York City, I was told that my salary would be $65 dollars per week. Since I had been supporting my husband, who was a medical intern, and myself for several months already, I knew that we could not manage on that pay and said so to the interviewer. “Well,” she explained, “the men in that position earn $110 because they are the family wage earner.”

“But I am the wage earner for my family,” I objected. “Why is that, dear?” she asked.

“Because my husband gets $30 a month at the hospital and has to use that money to launder his ‘whites’ (intern’s hospital uniforms).” “Oh, then we’ll pay you the $110,” she consented.

I left her office thrilled that I had the job, but my cheeks were burning because I felt like a second-class citizen. Some 10 years later, there was a class-action lawsuit from a large group of women employees against the company demanding equal pay for equal work. It took years, but eventually they won. This has been a private uphill fight, corporation by corporation, agency by agency, for what should be so obvious, and that struggle is still going on, more than 55 years later. The difference is that now it is a public matter and the injustice rings out to fill a sports stadium.

“It’s complicated,” answers the United States Soccer Federation, trying to explain where the money comes from and how it is allocated. To heck with that! It’s always complicated to right social wrongs, to win social change. Old views have to be altered, windows of the mind have to be opened. These women athletes have thrown those windows open wide.

Furthermore, why should I care whether the star player is gay? That makes as much difference as knowing whether she paints her toenails purple or showers in the morning or at night. Do I need to know if the orchestra conductor at Carnegie Hall is a Republican or a Democrat? Or whether the chef in my favorite restaurant is right-handed or left-handed?

Let’s get real. For those who refer to the “good ole days,” nostalgia can have its place. But I say thanks for the world we live in today, where any number of social injustices have come out of the woodwork and into the light. Before they can be changed, they must be acknowledged. Their emergence has been possible because of talented warriors like the U.S. women’s soccer team.

WMHO hosts Jewels & Jeans Gala

The Ward Melville Heritage Organization hosted its annual Jewels & Jeans Gala at Flowerfield in St. James on June 19. This year’s event honored Katharine Griffiths, Executive Director, Avalon Park & Preserve; Leah Dunaief, Editor and Publisher of Times Beacon Record News Media; Anna Kerekes, WMHO Trustee; and Andy Polan, President, Three Village Chamber of Commerce “for their outstanding achievements to the community.” The evening featured music by Tom Manuel and The Jazz Loft All Stars, cocktails, dinner and a live and silent auction.

Photos by Ron Smith, Clix|couture

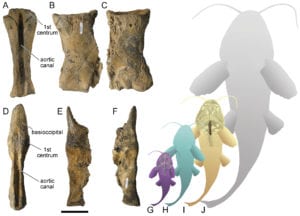

SBU’s Maureen O’Leary turns lack of access into ‘silver lining’ for ancient Saharan seaway

By Daniel Dunaief

Mali is filled with challenges, from its scorching hot 125 degree temperatures, to its sudden rainstorms, to its dangers from militant and terrorist-sponsored groups.

The current environment in the landlocked country in West Africa makes it extraordinarily difficult to explore the past in a region that includes parts of the Sahara Desert, but that, at one point millions of years ago, was part of a waterway called the Trans-Saharan Seaway.

Maureen O’Leary, professor of anatomical sciences at the Renaissance School of Medicine at Stony Brook University, led three expeditions to Mali, in 1999, 2003 and 2008, collecting a wide array of fossils and geological samples from areas that transitioned from an inland seaway that was about 50 meters deep on average to its current condition as a desiccated desert.

On her third trip, O’Leary quickly left because she decided the trip was too dangerous for her and the scientific team. Rather than rue the lack of ongoing access to the region, however, O’Leary pulled together an international team of researchers from Australia, the United States and Mali to look more closely and categorize the information the research teams had already collected from the region.

“We made the most of a bad situation,” O’Leary said. “It is a silver lining, to some degree.”

Indeed, O’Leary and her collaborators put together a paper for the June 28 issue of the Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History that is over 170 pages and contains numerous images of fossils, as well as recreations of a compelling region during a period from 100 million to 50 million years ago. This time period coincided with one of the five great prehistoric extinction events, during the Cretaceous-Paleogene boundary.

O’Leary characterized some of the more exciting fossil finds from the region, which include the first reconstruction of ancient elephant relatives and large predators such as sharks, crocodiles and sea snakes.

The size of some of these creatures far exceeds their modern relatives. For example, O’Leary’s scientific colleagues estimate that a freshwater catfish was about 160 centimeters in length, which is four times the total size of a modern catfish. The larger catfish dovetails with similar observations the researchers had made about sea snakes in 2016 and 2017. They started to knit this trend into a preliminary hypothesis in which a phenomenon known as island gigantism may have played a role in selecting for these unusually large creatures.

“Species become bigger in these environments,” O’Leary said, suggesting that other scientists have made similar observations. “It’s not clear what causes that kind of selection.”

In addition to studying vertebrate and invertebrate fossils, scientists including Eric Roberts at James Cook University in Australia looked at the geology of the region. Roberts helped name and describe many of the formations in the area. This provides context for the lives of creatures who survived in an environment distinctly different from the modern milieu of the Sahara Desert.

Roberts, who is a part of the Sedimentary Geology & Paleontology Research Group that has nicknamed themselves Gravelmonkeys, explained that his initial efforts in Mali came from the fieldwork over a course of weeks when he explored the rock sequences and took copious notes on them.

He suggested that the region still represents a geoscience frontier, in part because it is so difficult to get to, takes serious logistics to do fieldwork and is hard to maintain research.“Over many years, I have worked with collaborators on the project to analyze the samples in many different ways and especially to compare our notes and analytical results with descriptions of rocks and geological formations in other parts of the Sahara and further afield in Africa to understand how they are different and how they correlate,” he said.

O’Leary suggested that the paper provides some context for climate and sea level changes that can and have occurred. During the period she studied, the Earth was considerably warmer, with over 40 percent of today’s exposed land covered by water. Sea levels were about 300 meters higher than current levels, although the Earth wasn’t home to billions of humans yet or to many of the modern day species that share the planet’s resources.

O’Leary suggested that the paper provides some context for climate and sea level changes that can and have occurred. During the period she studied, the Earth was considerably warmer, with over 40 percent of today’s exposed land covered by water. Sea levels were about 300 meters higher than current levels, although the Earth wasn’t home to billions of humans yet or to many of the modern day species that share the planet’s resources.

Robert Voss, the editor-in-chief of the series at the American Museum of Natural History, praised the work for its breadth. “This was an unusually large and multidisciplinary author team, as appropriate for the broad scope of the report,” he explained .

“Seldom is such a large geographic area so poorly known paleontologically, so there was a unique opportunity here to break new ground and establish a broad framework for future work,” he added.

Voss described O’Leary as a “force of nature” who “responds constructively to peer reviews.” Roberts, too, appreciated the effort O’Leary put into this work.

O’Leary “drove the entire process and product,” which was only possible with someone of her “vision to wrangle so much science from so many different scientists into one place,” he offered in an email.

Roberts is very pleased with the finished product and added that it is “something that I will be proud of for the rest of my career. This took a lot of effort over the years and it great to see the end product.”

O’Leary said that much of the literature for the science in Mali was in French, which had kept it a bit below the radar for scientific discourse, which tends to be in English.

O’Leary said that much of the literature for the science in Mali was in French, which had kept it a bit below the radar for scientific discourse, which tends to be in English.

Indeed, O’Leary was able to facilitate conversations among the many people involved in this project because French was the common denominator language. She studied French at the Holton-Arms School in Bethesda, Maryland. “When I was sitting in my high school French class, I didn’t think it would come in so handy to be fluent in French” in her career, O’Leary said. “It was helpful as a female leader in this situation to be able to speak for [myself], whether speaking to other Americans or collaborating or working with guards.”

O’Leary plans to look at different projects in the United States, including in Puerto Rico, and in Saudi Arabia next. “We now have this synthetic story for Mali [and will be] building out from this to other areas. I anticipate a large time to ramp up to study areas like deposits in Nevada.”

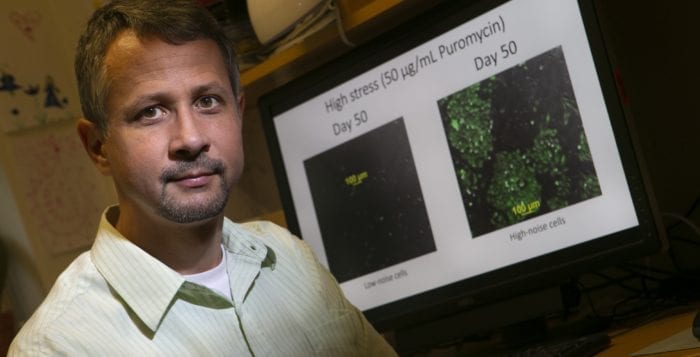

SBU’s Balázsi’s work has implications for drug resistance in cancer

By Daniel Dunaief

Take two identical twins with the same builds, skill sets and determination. One of them may become a multimillionaire, a household name and the face of a franchise, while the other may toil away at the sport for a few years until deciding to pursue other interests.

What causes the paths of these two potential megastars to diverge?

Gábor Balázsi, an associate professor in biomedical engineering at Stony Brook University, asked a similar question about a cellular circuit in the hopes of learning more about cancer. He wanted to know what is it about the heterogeneity of a cancer cell that makes one susceptible to treatment from chemotherapeutic drugs and the other resistant to them. Heterogeneity comes from molecular differences where the original causes may be subtle, such as two molecules colliding or a cell being closer to the tumor’s surface, while the consequences can create significant differences, even among cells with the same genes.

In research published this week in the journal Nature Communications, Balázsi used two mammalian cell lines that were identical except that each carried a different synthetic gene circuit that made one more heterogeneous than the other. He subjected the two cell lines, which would otherwise perform the same function, to various levels of the same drug to determine what might cause one to be treatable and the other to become resistant.

Through these mammalian cells, Balázsi created two circuits, one of which kept the differences between the cells low, while the other caused larger differences. Once inserted in the cell, these gene circuits created uniform and variable populations that could serve as models for low and high heterogeneity in cancer.

Working with Kevin Farquhar, who recently graduated from Balázsi’s lab, and former Stony Brook postdoc Daniel Charlebois, who is currently at the Department of Physics at the University of Alberta, Balázsi tried to test how uniform versus heterogeneous cell populations respond to treatment with different drug levels.

Using the two synthetic gene circuits in separate but identical cell lines, the Stony Brook scientists, with financial support from the National Institutes of Health and the Laufer Center for Physical and Quantitative Biology at SBU, could re-create high and low stochasticity, or noise, in drug resistance in two cell lines that were otherwise identical.

While the work is in its preliminary stages and is a long way from the complicated collection of genes responsible for various types of cancer, this kind of analysis can test the importance of specific processes for drug resistance.

“Only in the last decade or so have we come to realize how much heterogeneity (genetic and nongenetic differences) can exist within a tumor in a single patient,” Patricia Thompson-Carino, a professor in the Department of Pathology at the Renaissance School of Medicine at SBU, explained in an email. “Thinking of cancer in a single patient as several different diseases is a bit daunting, though currently, this heterogeneity and its direct effects on how the cancer behaves remains poorly understood.”

Indeed, Thompson-Carino added that she believes Balázsi’s work will “shed light on cancer cell responses to therapy. With the rise in cancer therapies designed to specific targets and the resistance that emerges in patients on these therapies, I think [Balázsi’s] work is of extremely high value” which may help with the puzzle of how nongenetic or epigenetic heterogeneity affects responses to treatment, she continued.

In the future, researchers and clinicians may look to develop new ways of biomarker analysis that considers the variability, rather than just the average level of a biomarker.

Balázsi suggested that looking only at the variability of cells is analogous to observing an iron block sinking in water. Someone might conclude that all solids sink in liquids. Similarly, scientists might decide that cellular variability always promotes drug resistance from observations when this happens. To gain a fuller understanding of the effect of variability, however, researchers need to equalize the averages. They then need to explore what happens at various levels of drug treatment.

Current therapies do not target heterogeneity. If such future treatments existed, doctors and scientists could combine ways of treating heterogeneity with attacking cancer, which might work in the short term or prevent cancer from recurring.

Balázsi suggests his paper is a part of his attempt to address three different areas. First, he’d like to figure out how to categorize patients better, including the variability of biomarkers. Second, he believes this kind of analysis will assist in creating future combinations of treatments. By understanding how the variability of cancer cells contributes to its reaction to therapies, he might help create a cocktail of treatments, akin to the effort that helped with the treatment of HIV in the lab.

Third, he’d like to obtain cancer samples and allow them to evolve in a lab, where he can check to see how they respond to treatment levels and administration scheduling. This effort could allow him to determine the optimal drug combination and dosing for a patient.

For the work that led to the current Nature Communications paper, Balázsi explored how mammalian cells respond to various concentrations of a drug. Over 80 percent of the genes in these cells are also present in human cells, so the mechanisms he discovered and conclusions he draws should apply to human cancer cells as well.

He concluded that cells with more heterogeneity, where the cells deviate more from the average, resist drugs better when the drug level is high. These same cells, show greater sensitivity when the drug is low.

Balázsi recognizes that the work he’s exploring is a “complex problem” and that it requires considerable additional research to understand and appreciate how a therapy might kill one cancer cell, while the same treatment in the same environment doesn’t have the same effect on a genetically identical cell.

Editorial: Congratulations 2019 high school graduates!

We congratulate each and every one the 2019 high school graduates in our circulation area. These students were born 18 years ago, at a time when planes deliberately took down the World Trade Center in New York City and crashed into the Pentagon in Washington, D.C., and a hillside in Shanksville, Pennsylvania. At around the time these children turned 8 years old, the U.S. and world economy collapsed after the financial industry bundled and sold bad mortgage debt. Currently, the nation and countries of the world are coping with election systems troubled with interference from foreign adversaries, whose interests aim to make people question the efficacy of democracy as a form of governance.

As we look forward, and put the past behind us, let’s make sure we take time to remind these graduates of the greater good of humankind. We should also celebrate the good nature within themselves to reassure these young adults that the future is perpetually full of hope and opportunity.

Over the last several decades, despite the tragedies, we have also seen many remarkable achievements. A nation elected its first black president, and we’ve seen women march for their rights and run and be elected to public office at historic rates. Aside from politics, over the last 20 years, scientists have sequenced human DNA, which is helping to develop effective treatments for cancer and other potentially deadly diseases. We’ve also watched the world change as the home computer and telecommunication turned mobile. Consequently, it’s become easier than ever to stay in touch. With the touch of a finger, we can access and enjoy the music, stories and performances of a world full of talented artists, writers and filmmakers.

Adversity and tumultuous times somehow, thankfully, spark creativity and inspire people’s inner goodness. Think of the ’60s, and how that peace and love-conquers-all theme galvanized a culture. It’s an age-old message, really, of biblical proportion. High school graduates should know that as caring human beings they already hold the core qualities they need to thrive.

D. None of the Above: Getting behind the wheel of our decisions

By Daniel Dunaief

We make them before we even get up. We lie in our beds, staring at our alarm clocks, where we are faced with the first of countless decisions. Should we get up now or can we afford to wait a few minutes before climbing out of bed?

Decisions range from the mundane to the mind blowing: Do you want pickles, lettuce and tomatoes and what kind of bread would you like; you’re taking a pay cut so you can do what job exactly; are you sure you want to sell that stock today when it may be worth more tomorrow?

We rarely take a step back from the decision-making process because we generally don’t want to slow our lives down, leaving us less time to make other decisions.

Some of the decisions we make are through a force of habit. We buy the same ketchup, take the same route to work, wear the same tie with the same shirt or call the same person when we are feeling lonely.

Just because we have always done something one particular way, however, doesn’t mean we made the best choice, or that we considered how the variables in our lives have changed over time.

As we age, we find that our needs, tastes and preferences evolve. Our bodies may have a lower caloric demand, especially if we spend hours behind a desk. We might also be more prepared to debate or argue with our priest or rabbi, or we might have a greater need to help strangers or make the world a better place for the next generation. The way we make decisions today may be inconsistent with the way we made them for the younger versions of ourselves.

We may have some of the same tastes for movies or books that we had 20 years ago. Then again, we may place a higher value on experiences than we do on possessions.

Eating a particular food, calling a person who makes us feel inadequate or sticking with the same assignments or jobs is often not the best way to live or enjoy our lives.

Inertia affects the way we decide on anything from whether to vote Democratic or Republican to whether we would like pasta or salad for lunch. Sure, I could defy the old me. But then am I remaking a decision or remaking myself?

Ah, but there’s the real opportunity: We can follow the Latin phrase “carpe diem” — seize the day — and redefine and reinvent ourselves as long as we do it with purpose and focus.

Sure, that takes work and planning and we might change something for the worse, but maybe we would make our lives better or leave our comfort zone for greater opportunities. We can decide to take calculated risks with our lives or to move in a new direction. After all, we teach our children to believe in themselves. And if we want to practice what we preach, we should believe in ourselves, too, even on a new path.

Why should we put our lives on automatic pilot and sit in the back seat, making the same circles month after month and year after year? Some routines and decisions, of course, are optimal, so changing them just to change won’t likely improve our lives.

But for many decisions, we can and should consider climbing back into the driver’s seat. For a moment, we might cause our paths to rock back and forth, as if we shook the wheel, but ultimately we can and will discover new terrain.