By Daniel Dunaief

Preserving the oceans of the world will take more than putting labels on sensitive areas or agreeing on an overall figure for how much area needs protection.

It will require consistent definitions, guidelines and enforcement across regions and a willingness to commit to common goals.

A group of 42 scientists including Ellen Pikitch, Endowed Professor of Ocean Conservation Sciences at the School of Marine and Atmospheric Sciences at Stony Brook University, recently published a new framework developed over more than 10 years in the journal Science to understand, plan, establish, evaluate and monitor ocean protection in Marine Protected Areas (MPAs).

“We’ve had MPAs for a long time,” said Pikitch. Some of them are not actively managed, with activities that aren’t allowed, such as fishing or mining, going on in them. “They may not be strongly set up in the first place to protect biodiversity. What this paper does is that it introduces a terminology with a lot of detail on when an MPA qualifies to be at a certain level of establishment and protection.”

These scientists, who work at 38 institutions around the world, created an approach that uses seven factors to derive four designations: fully protected, highly protected, lightly protected, and minimally protected.

If a site includes any mining at all, it is no longer considered a marine protected area.

Fully protected regions have minimal levels of anchoring, infrastructure, aquaculture and non-extractive activities. A minimally protected area, on the other hand, has high levels of anchoring, infrastructure, aquaculture and fishing, with moderate levels of non-extractive activities and dredging and dumping.

Using their own research and evidence from scientific literature, the researchers involved in this broad-based analysis wanted to ensure that MPAs “have quality protection,” Pikitch explained. “The quality is as important, if not moreso, than the quantity.”

The researchers are pleased with the timing of the release of this paper, which comes out just over a month before the United Nations’ Convention on Biological Diversity, which will meet virtually in October. Over 50 countries, including the United States, have already agreed to protect 30 percent of the ocean by 2030.

Pikitch called this a “critical time to get this information in front of decision makers.” The meeting will occur in two parts, with the second one set for an in-person gathering in China in April.

The point of the paper is to “help clarify what is an MPA, how do we distinguish different types and their outcomes,” Pikitch added.

The people who attend the CBD meeting range from high level government officials all the way up to the president of small countries.

About a decade ago, an earlier convention targeted protecting 10 percent of the oceans by 2020. The world fell short of that goal, with the current protection reaching about 7.7 percent, according to Pikitch.

Indeed, amid discussions during the development of this new outcome-based approach to MPAs, some researchers wondered about the logic of creating a target of 30 percent within the next nine years even as the world fell short of the earlier goal.

Some people at the meetings wondered “should we be pushing these things when a lot of them are failing?” Pikitch recalled of a lively debate during a meeting in Borneo. “Part of the answer is in this paper. These [earlier efforts] are failing because they are not doing the things that need to be done to be effective. It definitely helped us inform what we should be thinking about.”

Enabling conditions for marine protected areas go well beyond setting up an area that prevents fishing. The MPA guidelines in the paper have four components, including stages of establishment, levels of protection, enabling conditions and outcomes.

The benefits of ensuring the quality of protecting marine life extends beyond sustaining biodiversity or making sure an area has larger or more plentiful marine life.

“More often than not, it’s the case that MPAs do double duty” by protecting an environment and providing a sustainable resource for people around the area, Pikitch said. Locally, she points to an effort in Shinnecock Bay that provided the same benefits of these ocean protection regions.

In the western part of the bay, Pikitch said the program planted over 3.5 million hard clams into two areas. In the last decade, those regions have had an increase in the hard clam population of over 1,000 percent, which has provided numerous other benefits.

“It demonstrates the positive impact of having a no-take area,” Pikitch said.

At the same time, the bay hasn’t had any brown tides for four straight years. These brown tides and algal blooms can otherwise pose a danger to human health.

By filtering the water, the clams also make it easier for eel grass to grow, which was struggling to survive in cloudier waters that reduce their access to light. With four times as much eel grass as a decade ago, younger fish have a place to hide, grow and eat, increasing their abundance.

Being aware of the imperiled oceans and the threats humans and others face from a changing planet has sometimes been a struggle for Pikitch.

The marine researcher recalled a time when four hurricanes were churning at the same time in the Atlantic.

“I went to bed and I have to admit, I was really depressed,” Pikitch said.

When she woke up the next morning, she had to teach a class. She regrouped and decided on a strategic message.

“This is reality,” she told her class. “We have to accept this is the world we made. Everything we do that can make a positive difference, we do.”

Pikitch is encouraged by the work done to develop a new MPA framework.

These protected areas “provide a sustainable pathway to ensure a healthy ocean and to provide a home for future biodiversity,” she said.

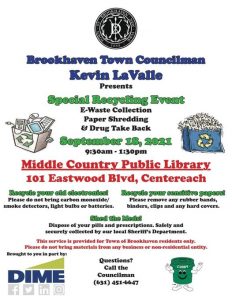

Brookhaven Town Councilman Kevin LaValle will present a special recycling event for Town of Brookhaven residents at Middle Country Public Library, 101 Eastwood Blvd., Centereach on Saturday, Sept. 18 from 9:30 a.m. to 1:30 p.m. with an e-waste collection, paper shredding and drug take back. Questions? Call 451-6647.

Brookhaven Town Councilman Kevin LaValle will present a special recycling event for Town of Brookhaven residents at Middle Country Public Library, 101 Eastwood Blvd., Centereach on Saturday, Sept. 18 from 9:30 a.m. to 1:30 p.m. with an e-waste collection, paper shredding and drug take back. Questions? Call 451-6647.