By Daniel Dunaief

Predicting extreme heat events is at least as important as tracking the strength and duration of approaching hurricanes.

Extreme heat waves, which have become increasingly common and prevalent in the western continental United States and in Europe, can have devastating impacts through wildfires, crop failures and human casualties.

Indeed, in 2003, extreme heat in Europe caused over 70,000 deaths, which was the largest number of deaths from heat in recent years.

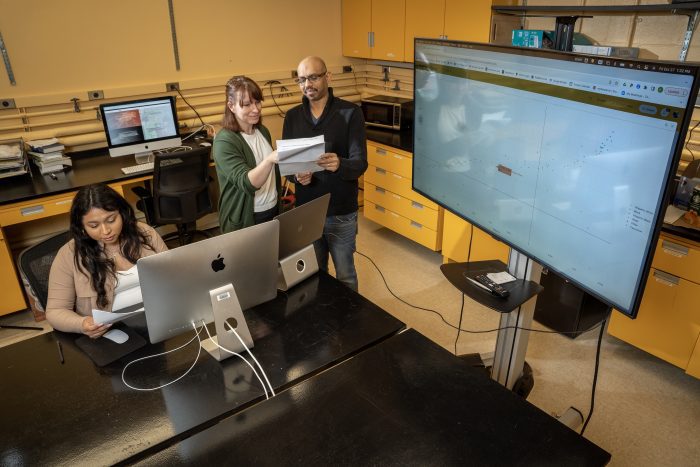

Recently, a trio of scientists at Stony Brook University’s School of Marine and Atmospheric Sciences (SoMAS) received $500,000 from the National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration to study heat events by using and analyzing NOAA’s Seamless System for Prediction and EArth System Research, or SPEAR, to understand heat waves and predict future such events.

The first objective is to evaluate simulations in the SPEAR model, by looking at how effectively this program predicts the frequency and duration of heat events from previous decades, said Ping Liu, who is the Principal Investigator on the project and is an Associate Professor at SoMAS.

Liu was particularly pleased to receive this funding because of the “urgent need” for this research, he explained in an email.

The team will explore the impact of three scenarios for increases in overall average temperature from pre-Industrial Revolution levels, including increases of 1.5 degrees Celsius, 2 degrees Celsius and four degrees Celsius, which are the increases the IPCC Assessment Reports has adopted.

Answering questions related to predicting future heat waves requires high-resolution modeling products, preferably in a large ensemble of simulations from multiple models, for robustness and the estimation of uncertainties, the researchers explained in their proposal.

“Our evaluations and research will provide recommendations for improving the SPEAR to simulate the Earth system, supporting NOAA’s mission of ‘Science, Service and Stewardship,’” they explained.

Kevin Reed, Professor, and Levi Silvers, research scientist, are joining Liu in this effort.

Liu and Reed recently published a paper in the Journal of Climate and have conducted unfunded research on two other projects. Liu brought Silvers into the group after Reed recommended Silvers for his background in climate modeling and dynamics.

Reed, who is Interim Director of Academic, Research and Commercialization Programs for The New York Climate Exchange, suggested that the research the heat wave team does will help understand the limitations of the SPEAR system “so that we can better interpret how the modeling system will project [how] blocking events and heat will be impacted by climate change.”

An expert in hurricanes, Reed added that blocking events, which can cause high pressure systems to stall and lead to prolonged heat waves, can also lead to unique hurricane tracks, such as Hurricane Sandy in 2012.

“A longer term goal of many of my colleagues at Stony Brook University is to better understand these connections,” said Reed, who is Associate Provost for Climate and Sustainability Programming and was also recently appointed to the National Academies’ Board on Atmospheric Sciences and Climate.

Liu will use some of the NOAA funds to recruit and train a graduate student, who will work in his lab and will collaborate with Reed and Silvers.In the bigger picture, the Stony Brook researchers secured the NOAA backing in the same year that the university won the bidding to develop a climate solutions center on Governors Island.

Reed suggested that the “results of the work can be shared with our partners and can help to inform future societally relevant climate research projects.”

Focus on two regions

The systems that have caused an increase in heat waves in the United States and Europe are part of a trend that will continue amid an uneven distribution of extreme weather, Liu added.

Heat waves are becoming more frequent and severe, though the magnitude and impact area vary by year, Liu explained.

The high pressure systems look like ridges on weather maps, which travel from west to east.

Any slowing of the system, which can also occur over Long Island, can cause sustained and uncomfortable conditions.

Over the past several years, Liu developed computer algorithms to detect high pressure systems when they become stationary. He published those algorithms in two journal papers, which he will use in this project.

Personal history

Born and raised in Sichuan, China, Liu moved to Stony Brook from Hawaii, where he was a scientific computer programmer, in November of 2009.

He and his wife Suqiong Li live in East Setauket with their 16-year old daughter Mia, who is a student at Ward Melville High School and a pianist who has received classical training at the Manhattan School of Music. Mia has been trained by award-winning teacher Miyoko Lotto.

Outside of the lab, Liu, who is five-feet, seven-inches tall, enjoys playing basketball on Thursday nights with a senior basketball team.

Growing up in China, Liu was always interested in weather phenomenon. When he was earning his PhD in China at the Institute for Atmospheric Physics at the Chinese Academy of Sciences in Beijing, he had limited computer resources, working in groups with IBM and, at times, Dell computer. He built several servers out of PC parts.

With air trapped inside the basin surrounded by tall mountains, Sichuan is particularly hot in the summer, which motivated him to pursue the study of heat waves.

Liu appreciated how Stony Brook and Brookhaven National Laboratory had created BlueGene, which he used when he arrived.

As for the future of his work, Liu believes predicting extreme heat waves is increasingly important “to help planners from local to federal levels cope with a climate that is changing rapidly and fostering more frequent and more severe heat events,” he explained.