By Daniel Dunaief

Clouds and rain often cause people to cancel their plans and seek alternative activities.

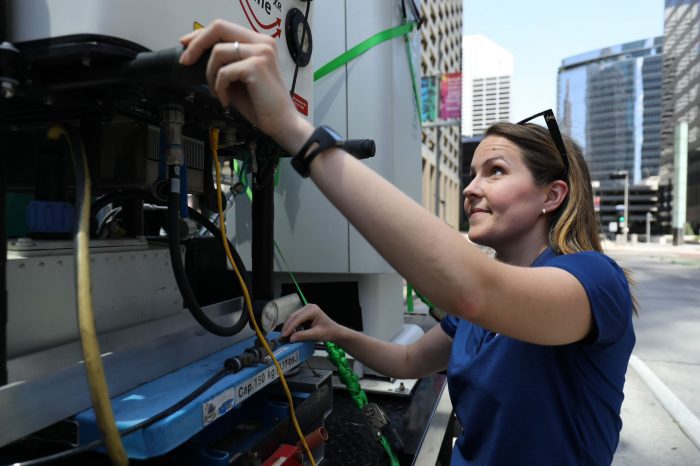

The opposite was the case for Katia Lamer this summer. A scientist and Director of Operations of Brookhaven National Laboratory’s Center for Multiscale Applied Sensing, Lamer was in Houston to participate in ESCAPE and TRACER studies to understand the impact of pollution on deep convective cloud formation.

With uncharacteristically dry weather and fewer of the clouds she and others intended to study, she had some down time and created a plan to study the distribution of urban heat. “I am always looking for an opportunity to grow the Center for Multiscale Applied Sensing and try to make the best of every situation,” she said.

Indeed, Lamer and her team launched 32 small, helium-filled party balloons. She and Stony Brook University student Zachary Mages each released 16 balloons every 100 meters while walking a one mile transect from the suburbs to downtown Houston. A mobile observatory followed the balloons and gathered data in real time through a radio link.

While helium-filled party balloons are not the best option, Lamer said the greater good lay in gathering the kind of data that will be helpful in measuring and monitoring climate change and explained that until some better balloon technology was available, this is what they had to use.

“Typically, we launch the giant radiosonde balloons, but you can’t launch them in a city,” she said because of the lack of space for these larger balloons to rise without hitting obstacles. The balloons also might pass through navigable airspace, disturbing flight traffic.

The smaller party balloons carried sensitive equipment that measured temperature and humidity and had a GPS sensor tucked into foam cups.

“If we can demonstrate that there is significant variability in the vertical distribution of temperature and humidity at those scales, then this would suggest that we should push to increase the resolution of our models to improve climate change projections,” she explained.

By following these balloons closely with a mobile observatory, Lamer and her team can avoid interference from other signals and signal blockage by buildings.

The system they used allowed them to select a cut-off height. Once the balloons reached that altitude, the string that connected the sensors to the balloon burns off and the sensors start free-falling while the balloon climbs until it pops.

The sensors collect continuous data on temperature, humidity and horizontal wind during the ascent and descent. Using the GPS, researchers can collect the sensors.

While researchers have studied urban heat using mesoscale models and satellite data, that analysis does not have the spatial resolution to understand community scale variability. Urban winds also remain understudied, particularly the winds above the surface, she explained.

Winds transport pollutants, harmful contaminants, and heat, which may be relieved on some streets and trapped on others.

Michael Jensen, principal investigator for the Tracking Aerosol Convection interaction Experiment, or TRACER and meteorologist at BNL, explained that Lamer is “focused on what’s going on in the urban centers.” Having a truck that can move around and collect data makes the kind of experiment Lamer is conducting possible. Jensen described what Lamer and her colleagues are doing as “unique.”

New York model

Lamer had conducted similar experiments in New York to measure winds. The CMAS mobile observatory’s first experiment took place in Manhattan around the One Vanderbilt skyscraper, which is 1,400 feet high and is next to Grand Central Terminal. No balloons were launched as part of that first experiment.She launched the small radiosonde balloons for the first time this summer in Houston around the 990 foot tall Wells Fargo complex.

Of the 32 balloons she and Mages launched, they collected data from 24. The group lost connection to some of the balloons, while interference and signal blockage disrupted the data flow from others.

Lamer plans to use the information to explore how green spaces such as parks and blue infrastructure including fountains have the potential to provide some comfort to people in the immediate area.

Such observations will provide additional insight beyond numerical models into how large an area a park can cool in the context of the configuration of a neighborhood.

This kind of urban work can have numerous applications.

Lamer suggested it could play a role in urban planning and in national security, as officials need to know the dispersement of pollutants and chemicals. Understanding wind patterns on a fine scale can help inform models that indicate areas that might be affected by an accidental release of chemicals or a deliberate attack against residents.

Bigger picture

Lamer is gathering data from cities to understand the scale of heterogeneity in properties such as heat and humidity, among others. If conditions are horizontally and vertically homogeneous, only a few permanent stations would be necessary to monitor the city. If conditions are much more varied, more measurement stations would be necessary.

One way to perform this assessment is to use mobile observatories that collect data. The ones Lamer has deployed use low-cost, research-grade instruments for street level and column wide observations.

Over the ensuing decades, Lamer expects that the specific conditions will likely change. Collecting and analyzing data now will enable scientists to develop a baseline awareness of typical urban conditions.

Scientific origins

A native of St.-Dominique, a small farmer’s village in Quebec Canada, Lamer was impressed by storms as she was growing up. She would often watch them outside her window, fascinated by what she was witnessing. After watching the Helen Hunt and Bill Paxton movie Twister, she wanted to invent her own version of the Dorothy instrument and start chasing storms.

When she spoke with her high school guidance counselor about her interest in tornadoes, which do not occur in Quebec, the counselor said she was the first person to express such a professional passion and had no idea how to advise her.

Lamer, who grew up speaking French, attended McGill University in Montreal, where she studied earth system science, aspects of geology and geography and a range of earth-related topics.

Instead of studying or tracking tornadoes, she has worked on cloud physics and cloud dynamics. Hearing about how clouds are the biggest wild card in climate change projections, she decided to embrace the challenge.

During her three years at BNL, Lamer, who lives with her husband and children in Stony Brook, has appreciated the chance to “push the envelope and be creative,” she said. “I really hope to stay in the field of urban meteorology.”