By Daniel Dunaief

Researchers regularly say they go wherever the science takes them. Sometimes, however, the results of their work puts them on a different path, addressing new questions.

So it was for Paul Freimuth, a biologist at Brookhaven National Laboratory. Freimuth was studying plant proteins of unknown function that he thought might play a role in the synthesis or modification of plant cell walls. The goal was to produce these proteins in bacteria or yeast to facilitate an understanding of the protein structures.

When he inserted plant genes into bacteria, however, one of those genes experienced a phase shift, producing a misfolded protein that, when produced in high enough quantities, killed the bacteria.

Working with several interns over the course of five years, as well as a few other principal investigators, Freimuth discovered that this protein had the same effect as antibiotics called aminoglycosides, which are the current treatment for some bacterial infections. He recently published the results of these studies in the journal Plos One.

Aminoglycosides enter the cell and cause ribosomes to create proteins in an error-prone mode, which kill the bacterial cells. The way these proteins kill the cells, however, remains a mystery. Antibiotic-treated cells produce numerous proteins, which makes determining the mechanism of action difficult.

The protein Freimuth studied mirrors the effect of treating cells with aminogylcosides. Researchers now have a protein they can study to determine the mechanism of cell killing.

To be sure, Freimuth said the current research is at an early stage, and is a long way from any application. He hopes this model will advance an understanding of how aberrant proteins kill cells. That information can enable the design of small molecule drugs that mimic the protein’s toxic effect. He believes it’s likely that this protein would be toxic if expressed in other bacteria and in higher cells, but he has not tested it yet.

With antibiotic resistance continuing to spread, including for aminoglycosides, Freimuth said the urgency to find novel ways to kill or inhibit bacterial growth selectively without harmful side effects has increased.

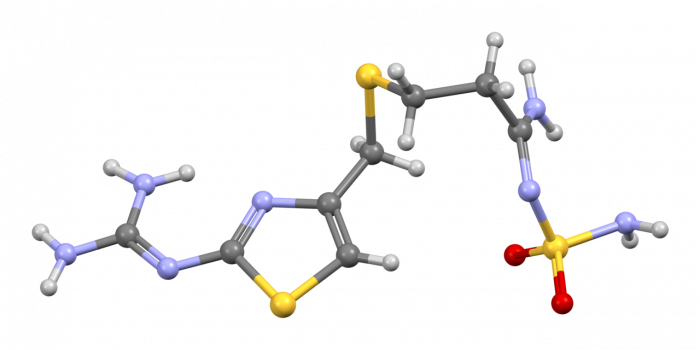

Aminoglycosides cause the ribosome to shift coding phases or to make other errors. The model toxic protein he studied resulted from the bacteria starting to translate amino acids at an internal position, which produced a new, and, as it turns out, toxic sequence of amino acids.

The phase-shifted gene contained a stop codon located just 49 codons from the start site, which means that the toxic protein only contained 48 amino acids, which is much shorter than the average of 250 to 300 amino acids in an E. coli protein.

Since the model toxic protein was gene-encoded rather than produced by an antibiotic-induced error in translation, Freimuth’s team were able to study the sequence basis for toxicity. The acutely toxic effect was dependent on an internal region 10 amino acids in length.

Narrowing down the toxic factor to such a small region could help facilitate future studies of the mechanism of action for this protein’s toxic effect.

Misread signal

Freimuth and his team discovered that the bacteria misread the genetic plant sequence the researchers introduced. The bacteria have a quality control mechanism that searches for these gibberish proteins, breaking them down and eliminating them before they waste resources from the bacteria or damage the cell.

When Freimuth raised the number of such misfolded proteins high enough, he and his colleagues overwhelmed the quality control system, which he believes happened because the misfolded protein affected the permeability of the cell membrane, opening up channels to allow ions to flood in and kill the cell.

He said it’s an open question whether the protein jams open existing channels or becomes directly incorporated into the membrane, compromising membrane stability.

He showed that cells become salt-sensitive, indicating that sodium ion concentration increases. At the same time, it is likely that essential metabolites are leaking out, depriving the cell of compounds it needs to survive.

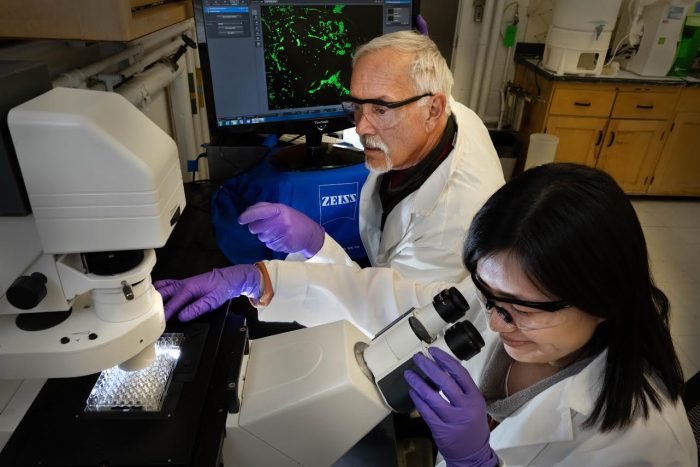

Now that the bacteria has produced this protein, Freimuth can use various tools and techniques at BNL, including the X-ray beamlines for protein crystallography and the cryo electron microscope, which would provide ways to study the interaction of the protein with cell components. High resolution structures such as the ones he hopes to determine could be used to guide drug design.

Freimuth is in the process of applying for National Institutes of Health funding for additional research, which could help the NIH’s efforts to counter the increasing spread of antibiotic resistance.

Freimuth has worked at BNL since 1991. He and his wife Mia Jacob, who recently retired from her role in graphic design in Stony Brook University’s Office of Marketing and Communication, reside in East Setauket.

The couple’s daughter Erika, who lives in Princeton and recently got married, works at Climate Central as an editor and writer. Their son Andrew works in Port Jefferson at an investment firm called FQS Capital Partners.

When Freimuth is not working at the lab, he enjoys sailing, kayaking and canoeing. During the pandemic, he said he purchased a small sailboat, with which he has been dodging the ferry in Port Jefferson Harbor.

Originally from Middletown, Connecticut, Freimuth was interested in science from an early age. He particularly enjoyed a mycology class as an undergraduate at the University of Connecticut.

As for his unexpected research with this protein, the biologist is pleased with the support he received from Brookhaven National Laboratory.

He said BNL enabled him to address the biofuel problem from protein quality control, which is a new angle. “BNL appreciates that valuable ideas sometimes bubble up unexpectedly and the lab has ways to assist investigators in developing promising ideas,” he said.