By Daniel Dunaief

It’s like a factory that makes bombs. Catching and removing the bombs is helpful, but it doesn’t end the battle because, even after many or almost all of the bombs are rounded up, the factory can continue to produce damaging products.

That’s the way triple-negative breast cancer operates. Chemotherapy can reduce active cancer cells, but it doesn’t stop the cancer stem cell from going back into the cancer-producing business, bringing the dreaded disease back to someone who was in remission.

Scientists who stop these cancer stem cells would be doing the equivalent of shutting down the factory, reducing the possible return of a virulent type of cancer.

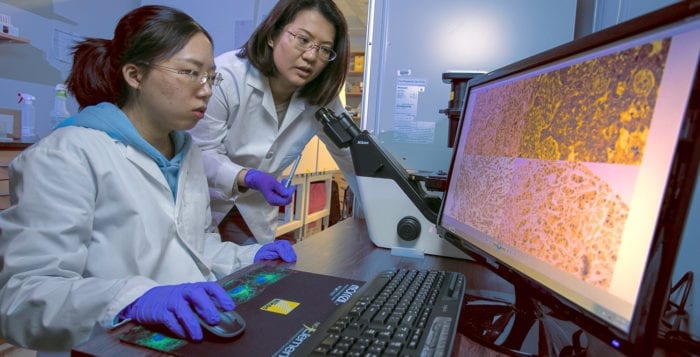

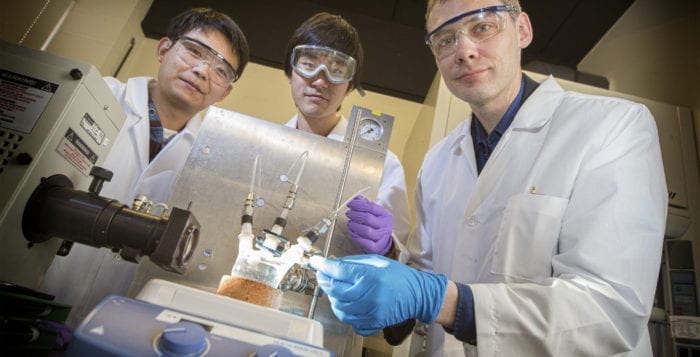

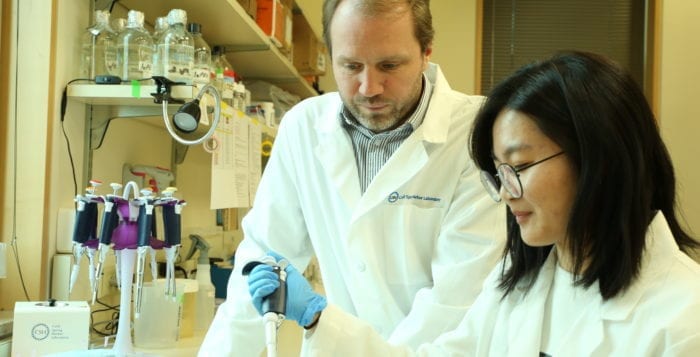

Lori Chan, an assistant professor in the Department of Pharmacological Sciences in the Renaissance School of Medicine at Stony Brook University, recently published research in Cell Death & Disease that demonstrated the role of a specific gene in the cancer stem cell pathway. Called USP2, this gene is overexpressed in 30 percent of all triple-negative breast cancers.

Inhibiting this gene reduced the production of the tumor in a mouse model of the disease.

Chan’s results “suggest a very important role [of this gene] in cancer stem cells,” Yusuf Hannun, the director of the Stony Brook University Cancer Center, explained in an email.

Chan used a genetic and a pharmacological approach to inhibit USP2 and found that both ways shrink the cancer stem cell population. She used RNA interference to silence the gene and the protein expression, and she also used a USP2-specific small molecular inhibitor to block the activity of the USP2 protein.

With the knowledge that the cancer stem cell factory population needs this USP2 gene, Chan inhibited the gene while providing doxurubicin, which is a chemotherapy treatment. The combination of treatments suppressed the tumor growth by 50 percent.

She suggested that the USP2 gene can serve as a biomarker for the lymph metastasis of triple-negative breast cancer. She doesn’t know if it could be used as a biomarker in predicting a response to chemotherapy. Patients with a high expression of this gene may not respond as well to standard treatment.

“If a doctor knows that a patient probably wouldn’t respond well to chemotherapy, the doctor may want to reconsider whether you want to put your patient in a cycle for chemotherapy, which always causes side effects,” Chan said.

While this finding is an encouraging sign and may allow doctors to use this gene to determine the best treatment, the potential clinical benefit of this discovery could still be a long way off, as any potential clinical approach would require careful testing to understand the consequences of a new therapy.

“This is the beginning of a long process to get to clinical trials and clinical use,” Hannun wrote. Indeed, researchers would need to understand whether any treatment caused side effects to the heart, liver and other organs, Chan added.

In the future, doctors at a clinical cancer center might perform a genomic diagnostic, to know exactly what type of cancer an individual has. Reducing the cancer stem cell population can be critically important in leading to a favorable clinical outcome.

A few hundred cancer cells can give rise to millions of cancer cells. “I want to let chemotherapy do its job in killing cancer cells and let [cancer stem cell] targeted agents, such as USP2 inhibitors, prevent the tumor recurrence,” Chan said.

She urges members of the community to screen for cancer routinely. A patient diagnosed in stage 1 has a five-year survival rate of well over 90 percent, while that rate plummets to 15 to 20 percent for patients diagnosed with stage 4 cancer.

The next step in Chan’s research is to look for ways to refine the inhibitor to make it more of a drug and less of a compound. She is also interested in exploring whether USP2 can be involved in other cancers, such as lung and prostate, and would be happy to collaborate with other scientists who focus on these types of cancers.

For Chan, the moment of recognition of the value of studying this gene in this form of breast cancer came when she compared the currently used drug with and without the inhibitor compound. With the inhibitor, the drug becomes much more effective.

A resident of Stony Brook, Chan lives with her husband, Joshua Lee, who is working in the same lab. The couple, who have a 1½-year-old rescue dog from Korea named KoKo, met when they were in graduate school.

Concerned about snow, which she hadn’t experienced when she was growing up in Taiwan, Chan started her tenure at Stony Brook five years ago on April 1, on the same day a snowstorm blanketed the area. “It was a very challenging first day,” she recalled. She now appreciates snow and enjoys the seasonal variety on Long Island.

Chan decided to pursue a career in cancer research after she volunteered at a children’s cancer hospital in Taiwan. She saw how desperate the parents and the siblings of the patient were. In her role as a volunteer, she played with the patients and with their siblings, some of whom she felt didn’t receive as much attention from parents who were worried about their sick siblings.

“This kind of disease doesn’t just take away one person’s life,” Chan said. “It destroys the whole family.” When she went to graduate school, she wanted to know everything she could about how cancer works.

Some day Chan hopes she can be a part of a process that helps doctors find an array of inhibitors that are effective in treating patients whose cancers involve the overexpression of different genes. “It would be a privilege to participate in this process,” she said.