By Daniel Dunaief

Long Island’s opioid-related use and poisoning, which nearly doubled from 2015 to 2016, was higher among lower income households in Nassau and Suffolk counties, according to a recent study in the American Journal of Preventive Medicine.

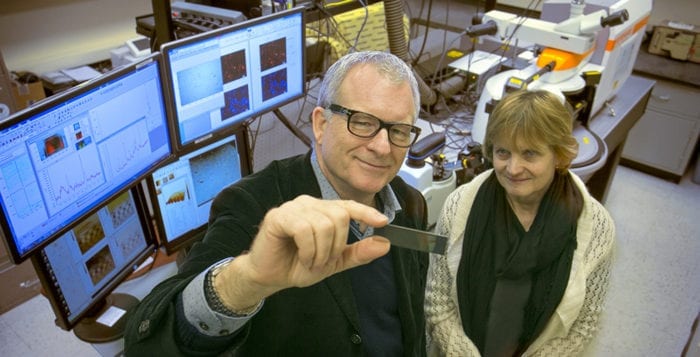

Looking at hospital codes throughout New York to gather specific data about medical problems caused by the overuse or addiction to painkillers, researchers including Fusheng Wang, an assistant professor in the Department of Biomedical Informatics at Stony Brook University, George Leibowitz, a professor in Stony Brook’s School of Social Welfare, and Elinor Schoenfeld, a research professor of preventive medicine at the Renaissance School of Medicine at Stony Brook, explored patterns that reveal details about the epidemic on Long Island.

“We want to know what the population groups are who get addicted or get poisoned and what are the regions we have to pay a lot of attention to,” Wang said. “We try to use lots of information to support these studies.”

The Stony Brook team, which received financial support from the National Science Foundation, explored over 7 years of hospital data from 2010 to 2016 in which seven different codes — all related to opioid problems — were reported.

During those years, the rates of opioid poisoning increased by 250 percent. In their report, the scientists urged a greater understanding and intervening at the community level, focusing on those most at risk.

Indeed, the ZIP codes that showed the greatest percentage of opioid poisoning came from communities with the lowest median home value, the greatest percentage of residents who completed high school and the lowest percentage of residents who achieved education beyond college, according to the study.

In Suffolk County, specifically, the highest quartile of opioid poisoning occurred in communities with lower median income.

Patients with opioid poisoning were typically younger and more often identified themselves as white. People battling the painkilling affliction in Suffolk County were more likely to use self-pay only and less likely to use Medicare.

In Suffolk County, the patients who had opioid poisoning also were concentrated along the western section, where population densities were higher than in other regions of the county.

The Stony Brook scientists suggested that the data are consistent with information presented by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, which has found significant increases in use by women, older adults and non-Hispanic whites.

“The observed trends are consistent with national statistics of higher opioid use among lower-income households,” the authors wrote in their study. Opioid prescribing among Medicare Part D recipients has risen 2.84 percent in the Empire State. The data on Long Island reflected the national trend among states with older residents.

“States with higher median population age consume more opioids per capita, suggesting that older adults consume more opioids,” the study suggested, citing a report last year from the American Journal of Preventive Medicine.

Nationally, between 21 to 29 percent of people prescribed opioids for pain misused them, according to the study, which cited other research. About 4 to 6 percent of people who misuse opioids then transition to heroin. Opioid costs, including treatment and criminal justice, have climbed to about $500 billion, up from $55.7 billion in 2007, according to a 2017 study in the journal Pain Physician.

The findings from the current study on Long Island, the authors suggest, are helping regional efforts to plan for and expand capacity to provide focused and targeted intervention where they are needed most.

Limited trained staff present challenges for the implementation of efforts like evidenced-based psychosocial programs such as the Vermont Hub and Spoke system.

The researchers suggest that the information about communities in need provides a critical first step in addressing provider shortages.

New York State cautioned that findings from this study may underreport the burden of opioid abuse and dependence, according to the study. To understand the extent of underreporting, the scientists suggest conducting similar studies in other states.

Scientists are increasingly looking to the field of informatics to analyze and interpret large data sets. The lower cost of computing, coupled with an abundance of available data, allows researchers to ask more detailed and specific questions in a shorter space of time.

Wang said this kind of information about the opioid crisis can provide those engaging in public policy with a specific understanding of the crisis. “People are not [generally] aware of the overall distribution” of opioid cases, Wang said. Each hospital only has its own data, while “we can provide a much more accurate” analysis, comparing each group.

Gathering the data from the hospitals took considerable time, he said. “We want to get information and push this to local administrations. We want to eventually support wide information for decision-making by the government.”

Wang credited his collaborators Leibowitz and Schoenfeld with making connections with local governments.

He became involved in this project because of contact he made with Stony Brook Hospital in 2016. Wang is also studying comorbidity: He’d like to know what other presenting symptoms, addictions or problems patients with opioid-related crises have when they visit the hospital. The next stage, he said, is to look at the effectiveness of different types of treatment.

A resident of Lake Grove, Wang believes he made the right decision to join Stony Brook. “I really enjoy my research here,” he said.

How often do we watch an interview with someone who has accomplished the unimaginable, who doesn’t know what to say or who is it at a loss for words when someone shoves a microphone in that person’s direction?

How often do we watch an interview with someone who has accomplished the unimaginable, who doesn’t know what to say or who is it at a loss for words when someone shoves a microphone in that person’s direction?