By Daniel Dunaief

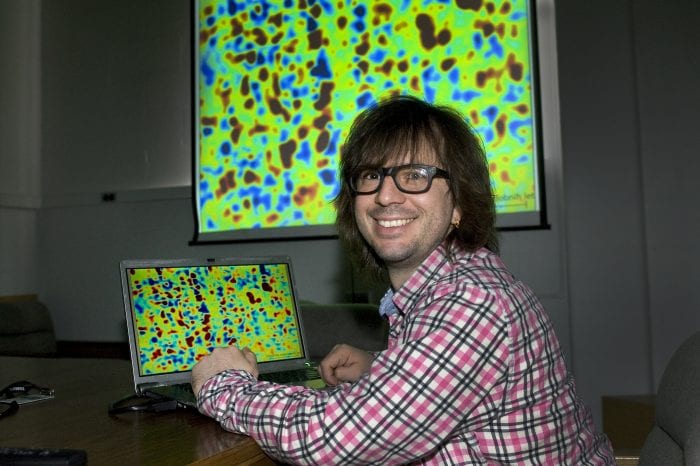

In joining Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Lucas Cheadle has continued his professional and personal journey far from his birthplace in Ada, Oklahoma.

Then again, his travels, which included graduate work in New Haven at Yale University and, most recently, post doctoral research in Boston at Harvard Medical School, wasn’t nearly as arduous or life threatening as the forced trip his ancestors had to take.

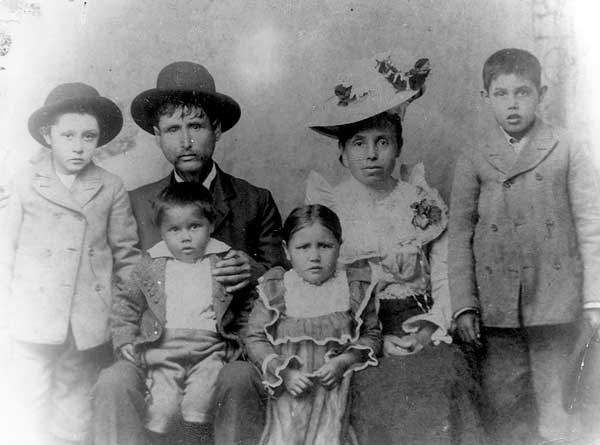

In 1837, Cheadle’s great, great, great grandparents had to travel from Pontotoc, Mississippi to southern Indian Territory, which is now near Tishomingo, Oklahoma as a part of the Trail of Tears. Native American tribes, including members of Cheadle’s family who are Chickasaw, cleared out of their lands to make way for Caucasian settlers.

Proud of his biracial heritage, which includes Chickasaw, Choctaw, and Cherokee lineages, Cheadle hopes to make his mark professionally in his studies of the development of the brain (see article on page B). At the same time, he hopes to explore ways to encourage other members of the Chickasaw tribe to enter the fields of science, technology, engineering and mathematics.

One of three sons of a mixed Chickasaw father named Robert Cheadle and a Caucasian mother named Cheryl, Cheadle would eventually like to provide the kind of internship opportunities through his own lab that he had during his high school years.

Indeed, during the summer of his junior year, Cheadle did a health care internship, in which he shadowed different types of physicians. He watched active surgeries and observed a psychiatrist during patient visits. After that summer, Cheadle thought he might become a psychiatrist as well because he knew he was interested in the study of the brain.

Down the road, Cheadle envisions having one or two people learn as interns in the lab during the summer. Longer term, Cheadle hopes other investigators might also pitch in to provide additional scientific opportunities for more Native American high school students.

Growing up in Oklahoma, Cheadle never felt he stood out as a member of the Chickasaw tribe or as a biracial student.

His father, Robert, was active with the tribe, serving as a tribal judge and then as a legislative attorney for the Chickasaw. His grandfather, Overton Martin Cheadle, was a legislator.

Through their commitment to the Chickasaw, Cheadle felt a similar responsibility to give back to the tribe. “It was an incredibly important part of their professional lives and it was a passion” to help others, he said. “I’m driven by that spirit.”

His father took people in who had nowhere to go. In a few cases, people he put up robbed the family. Even after they robbed him, Cheadle’s father took them back. When Robert Cheadle died earlier this year, one of the people whom Cheadle supported helped out with his funeral arrangements.

Driven to accomplish his mission as a scientist, Lucas Cheadle feels he can reach out to help high school students and others interested in science during his research journey.

“The better I can do, the more I can help,” Cheadle said. He hopes to “open doors for other people.”

With some of these efforts to encourage STEM participation among Native Americans, Cheadle hopes to collaborate with John Herrington, a Chickasaw astronaut who took a Native American flute into space during one of his missions. “It would be wonderful to discuss this” with Herrington, “if he has time for me,” said Cheadle.

In modern times, the Chickasaw tribe has made “good strides” in being successful. One challenge to that success, however, is that it has included assimilation.“The main goal is to hold onto the heritage as much as we can,” said Cheadle.

As for now, he plans to honor his heritage in his lab by “working hard to create a safe, respectful environment where people’s unique backgrounds and characteristics are supported and embraced. I try to create a space where diversity can thrive.”