By Daniel Dunaief

JoAnne Wilson-Brown was driving on Belle Mead Road, returning to her house in East Setauket with Easter Dinner and candy when Christmas came early.

Her 24-year old Ben, who tracks his parents on their cell phones and regularly checks up on them, was calling.

“Mom,” Ben said, “you need to be in Texas tomorrow.”

Ben, who left home seven years ago after graduating from Ward Melville High School when the Philadelphia Phillies chose him in the 33rd round of the major league baseball draft, was going to pitch for the Chicago Cubs in his first major league game against the defending World Series Champion Texas Rangers.

Ben also called his father Jody Brown, who had been working in the backyard on windows that he immediately put back in place so they could travel to The Ballpark in Arlington.

In his debut, Ben entered in the seventh inning. Perhaps fittingly, David Robertson, the pitcher the Cubs traded to the Phillies to acquire the hard throwing rookie Brown, pitched the top half of that same inning for the Rangers, allowing a hit without giving up a run.

Ben matched Robertson that first inning, giving up a lead off walk before inducing a groundout, strike out and line out to left field.

In his second inning of work, however, after getting three hours of sleep the night before, Brown allowed six runs on six hits in two third of an inning, leaving him with a tough introduction to “The Show” and an unsightly 32.40 earned run average.

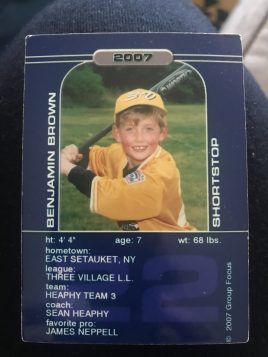

Ben’s debut is a microcosm of the journey he took to the pinnacle of baseball. An impressive and imposing high school player, the now six-foot, six-inch pitcher had such a stellar sophomore season that he attracted considerable attention from college scouts, receiving five offers.

In his junior year, however, Ben developed appendicitis, which forced him to spend time in the hospital.

After an appendectomy, Ben, who wanted to be a baseball player from the time he was two, had to return to the hospital.

“When they took him away in the gurney, he looked up at me and said, ‘Mom, is this going to be it [for his baseball career]? Do you think it’s all over?’” Wilson-Brown recalled.

Recognizing her son’s fierce determination, she instantly told him “absolutely not!”

Brown rebuilt his body and boosted his fastball sufficiently that the Phillies chose him at the age of 17 at the tail end of the draft.

In the seven years that followed, Brown endured Tommy John surgery, an oblique injury that robbed him of time on the field, and Covid, which shut down the minor league system.

Undeterred and with considerable support from his family including his mother, father Jody, brother James and sister Abbey, Ben remained focused amid those interruptions and put hours into himself and his craft, cutting out sugar from his diet, listening to anyone who could offer advice and dedicating himself to improving.

Brown also found love, marrying Maggie Seibert, a woman he met in church in Florida.

Ben “has put in so much work and made so many sacrifices,” said Ward Melville High School baseball coach Lou Petrucci, who speaks to his former student and pitcher at least once a week and whom Ben refers to as “another parent.”

After Ben was drafted, he arrived at the training camp in Clearwater, Florida, and talked to anyone and everyone about ways to improve.

Petrucci believes that Ben’s unquenchable thirst for baseball knowledge reflects an extension of the dedicated teachers in the Three Village school district who encouraged learning.

When graduates like Brown, former Met and current St. Louis Cardinals pitcher Steve Matz and current Yokohoma BayStars pitcher Anthony Kay advance in life, “it’s because of the K through 12 education” they received at the schools.

When Brown called Petrucci, whom he has known since he was a sixth grader in his class at Minnesauke Elementary School, to share the news about his promotion to the majors, Petrucci said, “Congratulations!

And, now, your next step is to make sure you stay there.”

Bouncing back

After that rough inning in his first game, Ben received considerable public and private support from his teammates and from baseball people he admires and respects.

Fellow Cub players publicly supported him, telling him that they couldn’t throw strikes in their first outing.

“It’s so encouraging when you’re a young guy,” said Ben. “You feel like you’re not alone when you get all this love from your teammates. It makes such a difference.”

Matz, who predicted Ben would be in the major leagues within five years of being drafted after he saw Ben as a late teenager, also offered him immediate support and encouragement. Matz “let me know I’m going to be okay,” said Brown. Matz told him he has “good stuff and I’m in a good spot.”

A soccer player at Clemson years ago, Ben’s father Jody Brown suggested that circumstances in baseball change quickly and “you have to have a very short memory.”

Ben made his debut at Wrigley Field, the Cubs historic home park, on April 3rd against the Colorado Rockies.

His parents trekked to Chicago for that outing as well.

“When we got to Chicago that first night, it was just after midnight,” Wilson-Brown said. “We turned that corner and saw Wrigley Field and it just took my breath away.”

She felt the same way her son did when they traveled to Cooperstown for the 12U tournament when he saw the immaculate fields.

At Wrigley, Ben came on in relief and pitched well, using the combination of his fastball and curveball to pitch four innings, allowing three hits and one run.

Ben’s first start came in San Diego, where he threw 4 2/3 innings without allowing the Padres to score.

A Red Sox fan growing up who had an enormous blanket of David Ortiz that filled most of one wall, Ben spoke after the game with Red Sox star-turned-analyst Pedro Martinez, who said on the show that Brown looked “sharp” and “clean.”

In his second start, Ben continued to impress, as he allowed one run on one hit in six innings against the Arizona Diamondbacks, the team that made it to last year’s World Series and that scored a record 14 runs in one inning in its home opener this year.

“It’s been a little bit of a roller coaster,” said Ben. He was pleased that he “threw the ball well” and left a “solid impression.”

With an earned run average down to 4.41 after his fourth game, Ben made a case for staying in the majors.

Getting there

The journey from East Setauket to the major league ballparks not only involved considerable work from Ben, but support from family, friends and coaches.

Indeed, Ben’s older brother James was instrumental in sharing his love for the game.

James “showed me how to be a ballplayer, how to wear my jersey right,” said Ben. “He toughened me up on the baseball field.”

Ben believes he “wouldn’t be in the big leagues” if his brother and father didn’t work with him every day, from hitting grounders and fly balls to him so he could practice his fielding to throwing a ball.

The Brown family appreciates the tireless support of numerous coaches, friends and family, who sometimes helped drive Ben to baseball events and encouraged him throughout his baseball growth.

Petrucci has watched many of Ben’s games over the years, reveling in the progress he’s made and wishing him well with each new opportunity.

When Ben was on the Phillies, he gave Petrucci a tee shirt with the words “Train to Reign.” Every time Ben pitched, Petrucci wore the shirt.

Playing for the Cubs has particular meaning for Maggie’s family, who, thanks to her stepfather Matt Pippin, are lifelong Cub fans.

Indeed, one of Ben and Maggie’s dog’s names is Wrigley.

When they were dating and Ben was still on the Phillies, Maggie gave him a Cubs shirt.

“I thought it was such a weird thing,” Ben recalls. “She gave me a shirt for a team I’m not playing for.”

When he was traded, it came “full circle. It’s all too good to be true,” Ben said.

Pippin learned that Ben was joining the Mets and recalled almost running off the road with excitement.

So, if a local restaurant decided to make a meal they named after him, the way the Se-Port Deli did for Matz, what should it be?

A large steak that comes from grass-fed beef with butter works for Ben, he said.

As for advice, Ben urged people who enter a field like baseball, with numerous competitors and obstacles, to work “harder than everybody else in the world,” especially when such a small percentage of people realize their baseball dreams. “When you want to do something that’s really difficult, lock in on the best path.”

Early on, Ben saw that path and pictured the future he is now living.

When he was 12, Ben joined one of his teams for a field trip to Shea Stadium. His mother asked him to pose for one more picture on the field before they left.

“Don’t worry” about the photo, Ben reassured her. “I’m going to be back here.”