Reviewed by Jeffrey Sanzel

“Plastic shapes human identity and speeds up the rate at which we move across the world and through our days, connecting people and allowing us to express who we are to each other. And yet plastic also helps us destroy. Plastic has saved our lives while taking others’ away. Plastic is a miracle. Plastic is a scourge.”

Erica Cirino’s Thicker Than Water (Island Press) is a frank and pointed examination of one of the most toxic elements of our “throwaway” culture. “Almost every single person alive today uses plastic on a daily basis, most of which is designed for minutes or seconds of use before it no longer serves a designated purpose.” Cirino, a gifted author whose writings have been featured in Scientific American and The Atlantic, has penned a smart, passionate exploration of one of the most troubling and challenging issues. Subtitled “The Quest for Solutions to the Plastic Crisis,” the book examines a problem of overwhelming global impact.

The book’s first part focuses on Cirino’s 3,000-mile journey on the S/Y Christianshavn to the Pacific Ocean’s Great Pacific Garbage Patch. Located in the turbulent North Pacific Gyre, this is “the most notoriously plastic polluted stretch of ocean in the world.” And while “the patch” has been described as a “static, floating pile of plastic” (i.e., a “plastic island”), the reality is much graver. “These waters are more akin to a soup to which humanity has added an unknown number of plastic items and pieces. The plastic is commonly suspended right below the surface, pushed just of out sight, constantly and unpredictably stirred by the rolling sea.” Her thesis is clear: While plastic defines our culture, it should not be allowed to determine our future.

The book features vivid descriptions. Whether depicting a meal or the rescue of a sea turtle from “ghost fishing,” nothing escapes her insight, expressed in often lyrical prose:

“Out at sea, time is not measured in hours or minutes, but by the intensity of the burning sun, the oscillating fade-sparkle-fade of thousands of stars and specks of glowing algae, the size and shape of the moon, the furor or calm of the sea […] The sea can show us what it is in life we need, and what we can live without.”

But the writing never masks the underlying and driving force of the dire situation.

Throughout, Cirino investigates the shift from the historical use of plants and animals to fossil fuels. She traces the involved reliance on the latter and the products created from it. She shares a comprehensive understanding. “Plastic is so permanent because of its structure on the molecular level.” She clarifies both microplastic and the even smaller particles—nanoplastic—and their invasion of the food chain.

The facts are harrowing. “About 40 percent of the plastic used today is actually not even really used by people—instead, as packaging, it covers or holds the foods and goods we purchase and is simply torn off and thrown away so we can access what’s inside.” The flimsy, disposable plastic is tossed, sometimes after a few moments’ use. “In 2015, experts estimated the amount of plastic in the oceans would outweigh fish by the year 2050 […] By 2020, humans had created enough petrochemical-based plastic to outweigh the mass of all marine and land animals combined, by a factor of two.”

And while the material presented is alarming, Cirino is never alarmist, never resorting to sensationalism. Instead, facing such devastating research, she maintains a fair and fairly objective view.

When on shipboard or in the laboratory, she presents the science to inform and engage the reader. There is a wealth of data from the manufacture of plastics to the associated chemical pollution, from oceans to fresh waters. For example, she depicts the research done on human-ingested plastic with a mannequin that emulates human breathing. Postdoc Alvise Vianello, from Denmark’s Aalborg University, states: “From what we can tell, it’s possible people are breathing in around eleven pieces of microplastic per hour when indoors.”

The third part of the book tackles the frequently ignored environmental racism. Industrial plants are commonly erected in minority communities. Cirino focuses on Welcome, Louisiana, and its environs. The area of Louisiana is home to about one hundred and fifty industrial plants, dubbed Cancer Alley. There is a great deal of corruption surrounding these factories and complexes, with the companies permanently damaging the communities with chemical pollution. Furthermore, often the factories are built on top of presumed burial grounds of enslaved African Americans. This section highlights both environmental and sociological devastation.

Cirino connects the dots from plastic production to climate change. She has a sense of the irony that the pandemic briefly lowered our carbon footprint. Additionally, as renewable energies rise, fossil fuel corporations—notably big oil and gas—counter the lack of demand by turning ancient carbon stocks into plastic.

The final section of the book, “Cleaning It Up,” centers on solutions. Technical invention (trash wheels, booms, grates, etc.) and grassroots work (simply picking up garbage) are important. But, ultimately, the solution is a combination of public awareness through education, science, and systemic change of using less, or ideally, no plastic. “You wouldn’t just mop up water off your floor if your bathtub were overflowing,” says Malene Møhl of Plastic Change. “You’d turn off the tap.”

Taxes, bans, and other legislation, combined with the search for biodegradable resources (even using bacteria, fungi, and algae), face pushback from large industries, the complexity of plastic recycling, and our own desire for convenience.

It would be impossible to read this powerful book and not look at the world differently, both in the larger picture and day-to-day life. Contents of Thicker Than Water can be overwhelming—even paralyzing. But, in the end, Erica Cirino’s ideas stimulate thought, raise awareness, and, most importantly, are a call to action.

Thicker Than Water is available at IslandPress.org, Amazon.com, or BarnesandNoble.com. For more information on the author, visit www.ericacirino.com.

The book contains accounts of orbs of light, dark silhouettes, footsteps in the middle of the night, and slamming doors. There are rooms where the temperature is exceptionally and inexplicably cold. There are scents with no source. But it is not about things that go bump in the night (though many do, including the voice of a screaming woman). Instead, it is about the energy and the presence (perhaps more blessed than haunted). Most of the encounters are with benign and even welcoming entities. Whether focusing on a member of the Culper Spy Ring, a library custodian, a mother guilty of filicide, or victims of a shipwreck, Brosky shows respect for her mission.

The book contains accounts of orbs of light, dark silhouettes, footsteps in the middle of the night, and slamming doors. There are rooms where the temperature is exceptionally and inexplicably cold. There are scents with no source. But it is not about things that go bump in the night (though many do, including the voice of a screaming woman). Instead, it is about the energy and the presence (perhaps more blessed than haunted). Most of the encounters are with benign and even welcoming entities. Whether focusing on a member of the Culper Spy Ring, a library custodian, a mother guilty of filicide, or victims of a shipwreck, Brosky shows respect for her mission.

Certainly, the hyper-articulate Calagun is the book’s unique character. Nicknamed “Figgie,” the aboriginal boy’s eloquence is a marvel: “Your perceptions of my intentions are somewhat askew.” A new oarsman in the Dawson crew, he becomes Savannah’s companion and champion. He serves as the gateway in her shift in perception. Through him, she sees the orcas anew and, subsequently, the world. Their interactions root in genuine respect and affection. “Some people are like empty bowls we can pour all our problems into, and Figgie was that way for me,” muses Savannah.

Certainly, the hyper-articulate Calagun is the book’s unique character. Nicknamed “Figgie,” the aboriginal boy’s eloquence is a marvel: “Your perceptions of my intentions are somewhat askew.” A new oarsman in the Dawson crew, he becomes Savannah’s companion and champion. He serves as the gateway in her shift in perception. Through him, she sees the orcas anew and, subsequently, the world. Their interactions root in genuine respect and affection. “Some people are like empty bowls we can pour all our problems into, and Figgie was that way for me,” muses Savannah.

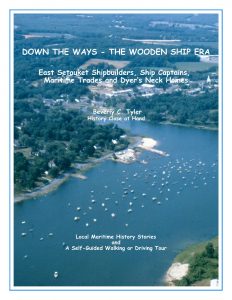

A special section focuses on the author’s grandfather, Captain Beverly Swift Tyler, who was a ship captain, boat builder, racing sailor, and boarding house owner. This unique and personal inclusion further brings to life the living history element of the writer’s undertaking.

A special section focuses on the author’s grandfather, Captain Beverly Swift Tyler, who was a ship captain, boat builder, racing sailor, and boarding house owner. This unique and personal inclusion further brings to life the living history element of the writer’s undertaking.

Tommy and Maria are Our Town’s George and Emily for a savvier time. While they are actively intimate, there is still innocence and awakening. Tommy is in the rush and flush of first love, where every moment means something: hours of phone calls, of anticipation. Lorenzo writes with accuracy, of hormones and hope, but also with kindness. His young people wade through their own truths and struggle with hypocrisies. There is sex and drugs, but there is also a genuine connection.

Tommy and Maria are Our Town’s George and Emily for a savvier time. While they are actively intimate, there is still innocence and awakening. Tommy is in the rush and flush of first love, where every moment means something: hours of phone calls, of anticipation. Lorenzo writes with accuracy, of hormones and hope, but also with kindness. His young people wade through their own truths and struggle with hypocrisies. There is sex and drugs, but there is also a genuine connection.

“The world has felt so chaotic over the past few years… an unlikely pandemic followed by US elections and so many crises around the world,” RabbiSaacks says after a few moments in thought. “Our minds are confronted by so much information on social media on a daily basis, we barely have time to decide what we think about a matter before we are bombarded by even more opinions. And these are important topics that require much thought and care.”

“The world has felt so chaotic over the past few years… an unlikely pandemic followed by US elections and so many crises around the world,” RabbiSaacks says after a few moments in thought. “Our minds are confronted by so much information on social media on a daily basis, we barely have time to decide what we think about a matter before we are bombarded by even more opinions. And these are important topics that require much thought and care.”

The earliest part of the book focuses on the biblical connections. Superman is most closely associated with Moses and Samson, but Schwartz also explores Superman as a Jesus figure. While the early Superman reflects an Old Testament figure, in film, television, and later incarnations, the Christ symbolism became strongest.

The earliest part of the book focuses on the biblical connections. Superman is most closely associated with Moses and Samson, but Schwartz also explores Superman as a Jesus figure. While the early Superman reflects an Old Testament figure, in film, television, and later incarnations, the Christ symbolism became strongest.