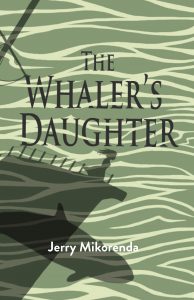

Book Review: ‘The Whaler’s Daughter’

Reviewed by Jeffrey Sanzel

There is a long tradition of Man vs. Nature in young adult literature. The Island of the Blue Dolphins, Hatchet, and even Call of the Wild (which straddles the world of adult and young adult fiction) are examples of the genre. These novels reflect how the individual changes when interacting with greater forces. Jerry Mikorenda’s The Whaler’s Daughter (Regal House Publishing) smartly explores the world of whaling in a 1910 New South Whales community.

In a small Australian station, the whalers have joined forces with orcas to hunt whales. Savannah Dawson, a twelve-year-old living with her widowed father, dreams of working alongside him on the boats, joining the family’s long whaling history. Her gender strongly impedes her desire. In addition, she believes that the orcas caused the death of her two brothers, Eli and Asa.

The book seamlessly weaves Savannah’s two journeys. First, her realization that the orcas were not responsible for her sibling’s death. Second, her struggle for acceptance as a crew member. The author addresses both issues throughout, using detailed research to infuse the book with a vivid portrait of life on ship and shore, the challenges of the sea, and the camaraderie of the men themselves. He touches on superstitions and familial connections. In addition, he contextually integrates both regional dialect and nautical/whaling vocabulary. (There is also a helpful appendix of terms.)

Mikorenda sets the tone and pace with Savannah’s declaration: “I began my day as I always did, lugging those dreaded pots to the fire pit to make a bushman’s stew. Their big iron bellies slogged through the sand as if they were drunken sailors being dragged to Sunday service.” He presents a life of physical toil with a heroine who has a wry sense of observation. She begins as a cook and ends on the boat.

Savannah’s palpable frustration seats in her knowledge of being a Dawson and the weight the name carries. But being female has relegated her to a second-class citizen. Apart from an unwanted suitor, she is almost unseen. So driven to claim her birthright, she boldly chops off her hair: “If Papa needed a boy for the boats, I’d meet him halfway.” The portrait is a girl coming to terms with maturity. She questions the father-daughter relationship. “How could things go so wrong between us when all I did was grow into who I am?” More telling is her realization that “Having your dreams trampled by someone who could help you realize them is worse than not having them at all.”

Savannah’s father, both distant and damaged, shows sensitivity in a revelation centering around a letter. His opening to Savannah is one of the most touching moments in the book. In addition, Mikorenda has populated the station with a blend of interesting and colorful sailors and their families. The locale is vibrant, with special note of the wonderfully eccentric Old Whalers and Seafarer’s Home, dubbed the Pelican House.

Certainly, the hyper-articulate Calagun is the book’s unique character. Nicknamed “Figgie,” the aboriginal boy’s eloquence is a marvel: “Your perceptions of my intentions are somewhat askew.” A new oarsman in the Dawson crew, he becomes Savannah’s companion and champion. He serves as the gateway in her shift in perception. Through him, she sees the orcas anew and, subsequently, the world. Their interactions root in genuine respect and affection. “Some people are like empty bowls we can pour all our problems into, and Figgie was that way for me,” muses Savannah.

Certainly, the hyper-articulate Calagun is the book’s unique character. Nicknamed “Figgie,” the aboriginal boy’s eloquence is a marvel: “Your perceptions of my intentions are somewhat askew.” A new oarsman in the Dawson crew, he becomes Savannah’s companion and champion. He serves as the gateway in her shift in perception. Through him, she sees the orcas anew and, subsequently, the world. Their interactions root in genuine respect and affection. “Some people are like empty bowls we can pour all our problems into, and Figgie was that way for me,” muses Savannah.

There is remarkable enculturation as Savannah learns from Figgie’s life experiences. Their burgeoning closeness hews tightly to the book’s heart. Figgie’s spirituality, acquired from his people, confirms man’s connection to the world: “We don’t own the earth, the earth owns us … This is where we began; this is where our spirits return to be reborn as a rock, bird, or fig tree.”

Figgie’s explanation of the balance of nature tempers Savannah’s anger with the orcas. Her newfound comprehension leads to an encounter with an orca bringing her to shore. Confusion leads to frustration, to awareness, to acceptance. Later, they witness the birth of an orca, furthering her understanding of the pod’s dynamic.

The novel offers a sense of the hard life in New Wales. It also gives a rich glimpse into aboriginal culture and beliefs. The blend matures Savannah in ways that life solely under her father would not give her.

The Whaler’s Daughter is an engaging novel. The plot is intense and eventful, and the language vivid and resonant. But the true strength lies in the growth of Savannah Dawson, a complex girl with challenging aspirations and the drive to see them fulfilled

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

A resident of Northport, Jerry Mikorenda’s work has appeared in The New York Times, The Boston Herald, The Gotham Center History Blog, and the 2010 Encyclopedia of New York City. His short stories have appeared in the San Francisco Chronicle, BULL, Cowboy Jamboree, and Gravel Magazine as well as other journals. His biography America’s First Freedom Rider: Elizabeth Jennings, Chester A. Arthur, and the Early Fight for Civil Rights was published in 2020. His latest, the coming-of-age historical fiction novel The Whaler’s Daughter, is perfect for middle-grade readers and is available online at Amazon and Barnes and Noble.

For more information, visit www.jerrymikorenda.com.