Reviewed by Jeffrey Sanzel

“Her job, her life calling, was about celebrating the beauty in art, and presenting it to the public, but now she was witnessing the wholesale theft and secreting of the world’s finest creations to unknown locations.”

The Art Spy [HarperOne] is Michelle Young’s account of Rose Valland’s heroic efforts in Paris of the 1940s to save some of the world’s most famous artwork from the Nazi invaders. Born in 1898, Valland earned degrees from the École des Beaux-Arts in Lyon and studied at the École des Beaux-Arts as well. She attained additional degrees from the École du Louvre and the Sorbonne. Overall, Rose spent nine years accumulating higher education and acquiring vast knowledge and skills.

Even though she was a denizen of the “crazy” Paris of the 1920s, the closeted Valland struggled to overcome a serious demeanor, most likely rooted in her sense of being out of place. She was a blacksmith’s daughter in the art world. Opinionated and articulate, she could remain seemingly humorless in social situations. “Rose had a reputation for being overly serious and too blunt for her own good, but her unflappability had proven useful in the war. She had learned to play the role of a nobody to the Nazis — not important enough to notice, not congenially enough to be flirted with, and too grave to be easy friends with.”

While highly schooled and exceptionally intelligent, she faced misogynistic setbacks, forcing her to work at Paris’s Jeu de Paume Museum as a volunteer. It was here that she was able to take a stand. No hurdles stopped her from doing her work and eventually saving hundreds, if not thousands, of paintings and sculptures.

Young’s thoroughly researched and engaging book follows Valland from the late 1930s to the mid-1940s in a world populated by the creations of luminaries like Salvador Dali, Max Beckman, Pablo Picasso, Henri Matisse, Paul Cezanne, Claude Monet, and many others. The Art Spy traces the early days of World War II throughout Europe, the anticipation of the incursion into Paris, followed by the exodus, and the ultimately desolate and abandoned city. Grounding her descriptions in detailed research, she evokes the visceral tensions of the time.

Young’s thoroughly researched and engaging book follows Valland from the late 1930s to the mid-1940s in a world populated by the creations of luminaries like Salvador Dali, Max Beckman, Pablo Picasso, Henri Matisse, Paul Cezanne, Claude Monet, and many others. The Art Spy traces the early days of World War II throughout Europe, the anticipation of the incursion into Paris, followed by the exodus, and the ultimately desolate and abandoned city. Grounding her descriptions in detailed research, she evokes the visceral tensions of the time.

The Art Spy is also the story of heinous oppression and vicious destruction at the hands of the most tyrannical regime in history, the Nazi party. The confiscation of great works of art is almost a minor crime in the pantheon of the evil that was the German government of World War II. However, the preservation of art speaks to universal humanity, just as the unlawful acquisitions reflect the dark and greedy nature of the perpetrators.

Young explores Hitler’s war on “degenerative art,” contrasting with the constant and unbridled theft by the Nazis. Among those Valland encountered on multiple occasions was Hitler’s second-in-command, the brutish Herman Göring, who, along with many Party members, stole untold numbers of paintings and invaluable works. Young gives insight into the destructive effect of authoritarianism on the freedom of art.

The author presents evocative, detailed descriptions of art evacuations, depicting empty walls with frames leaning against them, and the titles of the removed paintings hastily scrawled in chalk in the blank spaces above. She is unflinching in her assessment of the collaborationist Vichy government and the many who took advantage on both sides to loot France’s artwork. And, always at the center, is Valland, whose world is one of curators, collectors, and artists, but simultaneously one of constant danger. (This includes the arrest and imprisonment of her partner, Joyce Heer.)

Young wisely introduces the French art dealer, Paul Rosenberg, and traces his fate along with his family’s, including the son, Alexandre, who served with the Allies in Africa. By doing this, she puts a face to the horrors of the looting of Jewish property and the oppression and destruction of an entire community. She juxtaposes tracing the confiscation and “re-distribution” of Jewish possessions with the mass arrests and deportations, most of them ending in the gas chambers of Auschwitz, the notorious Polish death camp.

“Never once in four years did Rose let any concern for her own safety override her commitment to her mission. Not once did she allow her emotions to get the better of her or cloud her judgment [….] At great risk to her own life, she spied and documented, stole information, was subjected to degrading searches, and was expelled from the museum on multiple occasions. Each time, she returned and skillfully convinced the Germans to let her back in. In a war where resistance took many forms, she and her loyal guards at the Jeu de Paume fought to retain the humanity of those whose possessions, family histories, identities, and sometimes their lives were violently stolen from them. She did it all, as she put it, simply ‘to save a little beauty of the world.’”

Valland worked tirelessly after the war, recovering artwork and restoring it to its proper owners and museums. To this day, many works have not found their way back to the proper people, but Valland fiercely pursued justice late into her life.

“… No matter what atrocities take place, they’re always those who were willing to fight for what is right, no matter what the cost.” The life of Rose Valland—and Michelle Young’s important, astute documentation—is tribute to this powerful and necessary truth.

—————————————–

Author Michelle Young is a former resident of Setauket and 2000 graduate of Ward Melville High School where she was the salutatorian. She now divides her time between New York and Paris, and is an award-winning journalist, author, and professor of architecture at Columbia University. The Art Spy: The Extraordinary Untold Tale of WWII Resistance Hero Rose Valland is available at Barnes and Noble and Amazon.

Among her clients are the catfished Althea and the fifteen-year-old Riley, the latter struggling with indifferent parents and teenage angst. Again, Meister chooses not to shy away from easy roads or facile solutions. Guiding Joybird as a voice of reason is the upstairs neighbor, the youthful septuagenarian Betty, whose perfume “was an old-fashioned scent that made Joybird think of movies from the 1970s and big hoop earrings.” Betty functions as a friend and mother figure, advising the impossibility of always making people happy: “That’s a burden no one should have to carry.” The simple statement resonates deeply as Joybird’s newfound career presents unexpected landmines.

Among her clients are the catfished Althea and the fifteen-year-old Riley, the latter struggling with indifferent parents and teenage angst. Again, Meister chooses not to shy away from easy roads or facile solutions. Guiding Joybird as a voice of reason is the upstairs neighbor, the youthful septuagenarian Betty, whose perfume “was an old-fashioned scent that made Joybird think of movies from the 1970s and big hoop earrings.” Betty functions as a friend and mother figure, advising the impossibility of always making people happy: “That’s a burden no one should have to carry.” The simple statement resonates deeply as Joybird’s newfound career presents unexpected landmines.

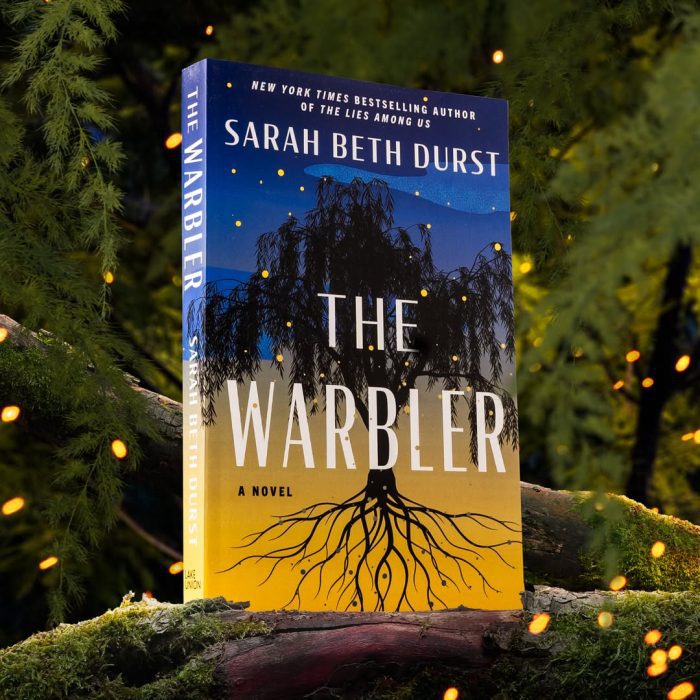

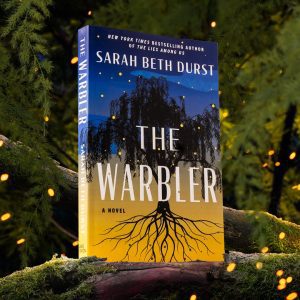

Durst populates The Spellshop with a wonderful integration of the expected and fantastical. Here, four-armed harpists dwell side-by-side with centaurs. The forest is full of cloud-like bear spirits and unicorns. Winged cats take up residence on roofs and shelter in attics during storms.

Durst populates The Spellshop with a wonderful integration of the expected and fantastical. Here, four-armed harpists dwell side-by-side with centaurs. The forest is full of cloud-like bear spirits and unicorns. Winged cats take up residence on roofs and shelter in attics during storms.

Rachel and Joon have been best friends since kindergarten, when they bonded over a pirate fantasy. Now, eleven years old, in July, between fifth and sixth grade, they have decided to be spies. Additionally, the inseparable pair are facing Joon’s imminent move out of the district, both fearing the toll the distance will take on their friendship.

Rachel and Joon have been best friends since kindergarten, when they bonded over a pirate fantasy. Now, eleven years old, in July, between fifth and sixth grade, they have decided to be spies. Additionally, the inseparable pair are facing Joon’s imminent move out of the district, both fearing the toll the distance will take on their friendship.

Did you ever think about self-publishing? Why did you go the traditional route?

Did you ever think about self-publishing? Why did you go the traditional route?