SBU’s Oliver Shipley identifies new creature in deep Bahama waters

By Daniel Dunaief

Oliver Shipley recently shared one of the mysteries of the heavily photographed but lightly explored deep sea areas near the Bahamas’ Exuma Sound.

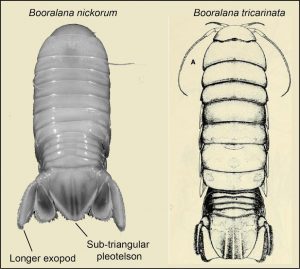

A Research Assistant Professor at Stony Brook University, Shipley and his colleagues published a paper in the journal Zootaxa describing a new species of isopod they named Booralana nickorum.

A few inches long, this isopod, which was found at a depth of about 1,600 feet, sheds light on some of the mysteries in these waters, offering a glimpse into areas mostly too deep for sunlight to penetrate.

“The level of knowledge on deep sea biodiversity anywhere in the Caribbean is very poor,” said Shipley. The scientists were specifically studying the biomass housed areas around The Exuma Sound.

In the Bahamas, the researchers are interested in preserving species biodiversity and identifying links between the shallow and deep-sea ecosystems, which can inform management of marine resources and help conserve biodiversity.

Shipley suggested it was “exciting” and, perhaps, promising that this area has already produced two isopods that are new species, both of which he described with low-cost technologies deployed off small boats.

“We haven’t even genetically sequenced 95 percent of the creatures that we’ve captured” which includes fish and sharks, Shipley said.

Brendan Talwar, a co-author on the paper describing the isopod and a Postdoctoral Scholar at Scripps Institution of Oceanography at UC San Diego, added that “this discovery is representative of the lack of knowledge” in this area. “You can swim from one environment, where almost every species is known or has been studied, to a place where almost nothing is known and almost nothing is studied.”

Finding new species could have numerous benefits, including in the world of drug discovery. To be sure, such findings require “many years of work and analysis” he said.

Still, such a possibility for future benefits exist, particularly as researchers catalog and study these creatures.

In the meantime, understanding individual species and the ecosystems in which they live can reveal information about how, depending on the biomass of various species, different places affect the cycling of gases such as carbon dioxide.

“When you find high biomass of a new species, it could have potentially huge implications for mitigating climate change,” said Shipley. “We have a primitive understanding of the Caribbean deep sea ecosystem. We don’t know the full effects or benefits and services of organisms that live in the deep ocean environment.”

In addition to finding organisms that might provide various benefits, scientists are also hoping to understand the “food web dynamics of the eastern Bahamas,” said Talwar.

Long road to identification

Shipley first saw an individual of this isopod species in 2013. Over time, he has since identified numerous other individuals.

The region in which Shipley identified this isopod has several potential food or energy sources. The deep sea area is in close proximity to shallower sea grass beds, which are closer to the surface and use light to generate food and energy through photosynthesis.

The tides and currents wash that sea grass into the deeper territory, sending food towards the deeper, darker ocean.

Energy also likely comes from coral reef productivity as reefs line the edge of the drop off.

Additionally, animals that traverse the shallower and deeper areas, whose poop and bodies sink, can provide food sources to the ecosystem below.

“There may be multiple sources of productivity which combines to promote a high level of biodiversity” in the ecosystem below, said Shipley.

The isopod Shipley and his collaborators identified lives in a pressure that is about 52 times the usual atmospheric pressure, which would be extremely problematic for organisms like humans. Isopods, however, have managed to live in most major ecosystems around the planet, including on mountains, in caves and in the deep sea.

“There’s something about that lineage that has supported their ability to adapt to a variety of environments,” said Shipley.

To bring the creatures back to the surface for study, researchers have used deep sea traps, including crustacean and eel traps, that are attached to a line. People working on boats then retrieve those traps, which can take one to two hours to pull to the surface.

When they are brought to the surface, many animals suffer high mortality, which is a known sensitivity of deep-sea fisheries.

“We must gain as much knowledge as possible from each specimen,” Shipley explained

Scratching the surface, at depth

Talwar and Shipley have each ventured deep into the depths of The Exuma aboard a submersible.

The journey, which Talwar described as remarkably peaceful and calm and akin to an immersive aquarium experience, is “like a scavenger hunt,” he said.

When scientists or the sub pilot see a new species of sea cucumber, the pilot can move the sub closer to the organism and deploy the manipulator arm to store it in a collection box. Shipley and others hope to explore deep sea creatures under conditions akin to the ones in which they live in high pressure tanks on land.

Talwar described Shipley as “an extremely productive scientist” who works “incredibly hard.” Talwar also appreciates how Shipley will put collaborative projects at the top of his list, which is “fairly unique in a field where people are so busy with their own stuff.”

Shipley, who lives in Austin, Texas with his girlfriend Alyssa Ebinger, explained that researchers are pushing to support scientific leadership by Bahamians to conserve marine resources threatened by climate change.

Looking under rocks

As a child, Shipley, who grew up in York, England, spent about three years in Scotland, where they spent time at a beach called Trune.

“I remember looking in rock pools, picking up stuff and inspecting it,” he said. He was naturally inquisitive as a child.

While Shipley enjoys scuba diving and is a committed soccer fan — his favorite team is Leeds United — he appreciates the opportunity to build on his childhood enthusiasm to catalog the unknowns of the sea. He’s so inspired by the work and exploration that it “doesn’t feel like a job,” he said. He’s thrilled that he gets paid “to do all this exciting stuff.”