By Elizabeth Kahn Kaplan

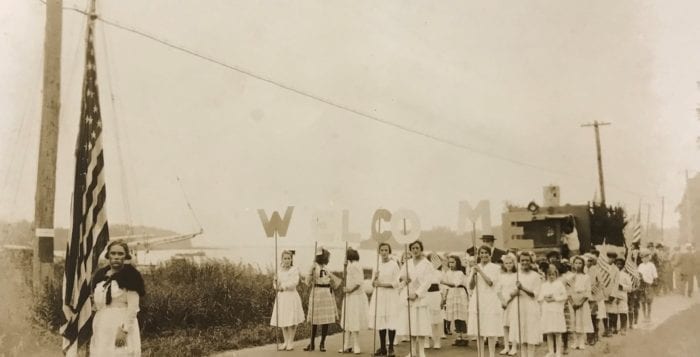

Twenty-seven enthusiastic day trippers boarded a chartered bus at the headquarters of the Three Village Historical Society at dawn on Nov. 3. Led by TVHS historian Bev Tyler, they arrived in comfort before 10 a.m. at Philadelphia’s newest tribute to the founding of our nation, the Museum of the American Revolution. There, the drama of the American Revolution and the ideas that inspired it came to life through the personal stories of the people who were there, from the early stirrings of unrest in Boston to the opening shots of the War of Independence and beyond, to the creation of the American Republic.

A must see was the recently opened exhibit, Hamilton Was Here: Rising Up in Revolutionary Philadelphia, on display through March 17, 2019. While New York City, our nation’s first capital, is the focus of attention in the Broadway hit “Hamilton: An American Musical,” it was in Philadelphia, the second national capital, that many of the major events in the life and work of Alexander Hamilton took place.

The exhibition highlights different aspects of Hamilton’s contributions: his role as an artillery officer in Washington’s army and, later, as adviser to President Washington; his writings that persuaded states to accept the United States Constitution; creator of the U.S. Coast Guard; and first Secretary of the Treasury who envisioned the financial future of the nation.

Through interactive displays, hands-on activities and wall texts, the museum presents the struggles by Hamilton, who favored a strong central government, with Jefferson and Madison, who believed that power should lie with each state. These are questions that we still struggle with today: How do we achieve a proper balance between the rights of each state to act independently and the need for federal oversight?

Other permanent exhibits are exceptional as well. The museum proudly displays Washington’s war tent, in which he worked and slept alongside Continental Army battlefields. Another remarkably stirring exhibit is housed in a small amphitheater containing life-size, three-dimensional representations of members of the Oneida Indian Nation. Each one “speaks” in turn, presenting arguments for and against sending their warriors to take part in the Saratoga Campaign in the autumn of 1777. Should they support the Patriot cause and fight alongside the Americans, or should they side with the British Army? The Oneidas wrestle with their decision and decide to fight with the Continental Army. The Saratoga Campaign became a turning point of the war.

Is this an appropriate museum for children? Yes, bring a child to see Washington’s war tent, or follow the 10 steps it takes to load and fire a cannon, or design a coin or paper currency for the new nation, or dress up in reproduction 1790s clothing to attend one of Martha Washington’s “levees.” All can sit in comfort to see excellent, informative short films.

That said, the museum’s exhibits appear to be designed primarily for high school and college students and adults. They pose serious questions — questions that the nation still struggles to answer. At the end of the day I asked one of the knowledgeable participants among the group to share his impression. “It was good,” he said, “but not great.” When asked why the lower rating, he said, “Too politically correct.”

Hmm. Yes, the museum has expanded upon the history many of us learned about our country’s origins, mostly told from the perspective of affluent white Protestant males. Little was said in most textbooks or high school class discussions about the impact of the American Revolution on Native Americans, enslaved Africans, women, Catholics and other religious minorities and French and Spanish occupants of the land. For them, the revolution offered promise and peril. Some chose the cause of independence and others sided with the British.

Storybook touch screens called Finding Freedom introduce the African-American London Pleasants, who ran away from slavery in Virginia in 1781 and joined the British Army as a trumpeter. We hear about Eve, owned by the Randolph family of Williamsburg, Virginia, who fled to the British when they occupied the city. She and her son George enjoyed a period of freedom, working under the British, until she was recaptured at Yorktown in 1781. We learn of Elizabeth Freeman, who sued her owner for freedom based on the 1780 Massachusetts Constitution — and won.

The museum focuses attention on the most revolutionary legacies — personal liberty, citizenship, the right to vote and social equality. Is the museum “Politically Correct,” or simply “Correct”?

On the bus ride back to Setauket, the participants from the Three Village Historical Society were treated to a screening of the TBR News Media film about Nathan Hale, “One Life to Give.” They also had time to think about what they’d learned at the Museum of the American Revolution. If that was the goal of its designers, they accomplished their purpose.

The author is the former director of education at the Three Village Historical Society and an educator, writer and lecturer on art, artists and American history.

All photos by Elizabeth Kahn Kaplan