By Daniel Dunaief

Priya Sridevi started out working with plants but has since branched out to study human cancer. Indeed, the research investigator in Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Cancer Center Director David Tuveson’s lab recently became the project manager for an ambitious effort coordinating cancer research among labs in three countries.

The National Cancer Institute is funding the creation of a Cancer Model Development Center, which supports the establishment of cancer models for pancreatic, breast, colorectal, lung, liver and other upper-gastrointestinal cancers. The models will be available to other interested researchers. Tuveson is leading the collaboration and CSHL Research Director David Spector is a co-principal investigator.

The team plans to create a biobank of organoids, which are three-dimensional models derived from human cancers and which mirror the genetic and cellular characteristics of tumors. Over the next 18 months, labs in Italy, the Netherlands and the United States, at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, expect to produce up to 150 organoid models.

The project officially started in January and the labs have been setting up the process through June. Sridevi is working with Hans Clevers of the Hubrecht Institute, who pioneered the development of organoids, and with Vincenzo Corbo and Aldo Scarpa at the University and Hospital Trust of Verona.

Sridevi’s former doctoral advisor Stephen Alexander, a professor of biological sciences at the University of Missouri, said Sridevi has had responsibilities beyond her own research. She was in charge of day-to-day operations in his lab, like ordering and regulatory reporting on radioactive material storage and usage, while he and his wife Hannah Alexander, who was Sridevi’s co-advisor, were on sabbatical. “She is hard working and determined,” said Alexander. “She knows how to get things done.”

In total, the project will likely include 25 people in the three centers. CSHL will hire an additional two or three scientists, including a postdoctoral researcher and a technician, while the Italian and Netherlands groups will also likely add another few scientists to each of their groups.

Each lab will be responsible for specific organoids. Tuveson’s lab, which has done considerable work in creating pancreatic cancer organoids, will create colorectal tumors and a few pancreatic cancer models, while Spector’s lab will create breast cancer organoids.

Clevers’ lab, meanwhile, will be responsible for creating breast and colorectal organoids, and the Italian team will create pancreatic cancer organoids. In addition, each of the teams will try to create organoids for other model systems, in areas like lung, cholangiocarcinomas, stomach cancer, neuroendocrine tumors and other cancers of the gastrointestinal tract.

For those additional cancers, there are no standard operating procedures, so technicians will need to develop new procedures to generate these models, Sridevi said. “We’ll be learning so much more” through those processes, Sridevi added. They might also learn about the dependencies of these cancers during the process of culturing them.

Sridevi was particularly grateful to the patients who donated their cells to these efforts. These patients are making significant contributions to medical research even though they, themselves, likely won’t benefit from these efforts, she said. In the United States, the patient samples will come from Northwell Health and the Tissue Donation Program of Northwell’s Feinstein Institute of Medical Research. “It’s remarkable that so many people are willing to do this,” Sridevi said. “Without them, there is no cancer model.”

Sridevi also appreciates the support of the philanthropists and foundations that provide funds to back these projects. Sridevi came to Tuveson’s lab last year, when she was seeking opportunities to contribute to translational efforts to help patients. She was involved in making drought and salinity resistant rice and transgenic tomato plants in her native India before earning her doctorate at the University of Missouri in Columbia.

Alexander recalled how Sridevi, who was recruited to join another department at the University of Missouri, showed up in his office unannounced and said she wanted to work in his lab. He said his lab was full and that she would have to be a teaching assistant to earn a stipend. He also suggested this wasn’t the optimal way to conduct research for a doctorate in molecular biology, which is a labor-intensive effort. “She was intelligent and determined,” Alexander marveled, adding that she was a teaching assistant seven times and obtained a wealth of knowledge about cell biology.

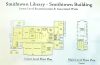

Sridevi, who lives on campus at CSHL with her husband Ullas Pedmale, an assistant professor at CSHL who studies the mechanisms involved in the response of plants to the environment, said the transition to Long Island was initially difficult after living for six years in San Diego.

“The weather spoiled us,” she said, although they and their goldendoodle Henry have become accustomed to life on Long Island. She appreciates the “wonderful colleagues” she works with who have made the couple feel welcome.

Sridevi believes the efforts she is involved with will play a role in understanding the biology of cancer and therapeutic opportunities researchers can pursue, which is one of the reasons she shifted her attention from plants. In Tuveson’s lab, she said she “feels more closely connected to patients” and is more “directly impacting their therapy.” She said the lab members don’t get to know the patients, but they hope to be involved in designing personalized therapy for them. In the Cancer Model Development Center, the scientists won a subcontract from Leidos Biomedical Research. If the study progresses as the scientists believe it should, it can be extended for another 18 months.

As for her work, Sridevi doesn’t look back on her decision to shift from plants to people. While she enjoyed her initial studies, she said she is “glad she made this transition” to modeling and understanding cancer.