Bright Spots on Earth Day

By Carl Safina

When I was 15 or so, an older neighbor took me fishing to his secret pond in Flanders. It was 1970, the year of the first Earth Day. He led me along a narrow trail through the pine woods to his special spot. It was a modest-sized pond, and the first thing I noticed was that right across the shore was a huge nest made of big sticks. It was a little dilapidated. Abandoned.

I’d always loved birds. And among birds, I particularly was thrilled by hawks, eagles, and falcons. But living in a cookie-cut suburb of central Nassau County, my real-world contact with wild nature at that time was very limited. Much of what I knew was from books. I knew what that nest was. And I knew why it was abandoned.

It belonged to a spectacular species I’d never seen: huge fish hawks called ospreys. And I knew, also — from reading Newsday and Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring — that I would probably never see them because DDT and other hard pesticides had caused all their eggs to break. Adults were now dying off wholesale due to old age, and ospreys were already erased from most of the region.

I knew all this from reading, but actually seeing that nest made me realize in a very visceral way how narrowly I’d missed growing up in a world that contained what it was supposed to contain. I could not believe the bad luck of the timing of my life.

And speaking of bad timing; that same year The New York Times Magazine ran a story on my favorite bird — another that I had only read about and seen photos of. The title of the story: Death Comes To The Peregrine Falcon. I would never see my favorite bird, because the same pesticides that were snuffing out ospreys had also wiped peregrine falcons from their cliff-nests from the New England to the West Coast and indeed all across Europe.

Bald eagles — forget it. A few left in places like southern Florida and Alaska, places I was sure I would never get to.

I assumed the trends would continue. I did not yet know that a small group of people based in a place called East Setauket were about to sue for the cessation of aerial spraying of DDT and some other chlorinated hydrocarbon pesticides. But they did. More surprising — they won!

In a few years, with those pesticides banned, the new Endangered Species Act in place, and the Clean Air Act, Clean Water Act, and National Environmental Policy Act signed into law by a president named Nixon, the natural environment became noticeably cleaner.

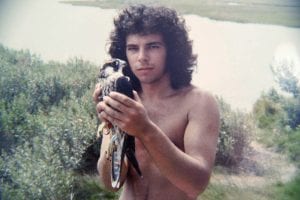

Scientists at Cornell University had succeeded in breeding some of the last peregrine falcons in the U.S. — hatchlings collected in Arctic Alaska. So in 1976, I drove up to Ithaca, tucked my long hair under my collar, and entered the office of the breeding facility to make the strongest case I could muster for why I would be a good candidate for helping to release the first generation of captive-bred peregrine falcons into a world newly cleansed of the worst pesticides of the time.

And thus I started my professional career by securing the first of several dream jobs, spending part of the summer caring for and managing the release of three precious falcon chicks that were not just birds; they were three promises we were making to ourselves and to the future of Life on Earth. If it was going to be up to us — and it was, of course — this wondrous species, the fastest living thing in the world, would not vanish from this planet.

That was also the year that I saw an osprey in Cold Spring Harbor.

Other Cornell scientists, who refused to see our ospreys wither into oblivion, moved viable eggs from remaining Chesapeake pairs to failing Long Island nests, keeping a few remnant pairs on reproductive life-support so that a smattering of new young birds might survive and return to the region.

It all started working. Ospreys did start coming back, laying eggs that no longer broke. Slowly at first and then to a degree I never could have imagined, ospreys recovered and came off the Endangered Species list. New York City now hosts the densest known nesting population of peregrine falcons in the world, sited on bridges and tall buildings, back in the Hudson’s Palisades, and even, locally, around Port Jefferson Harbor.

Bald eagles are nesting on Long Island for the first time in our lives, with perhaps a dozen pairs now, and regular sightings in our Setauket and Stony Brook communities. All of that we owe to the few, early, never-say-die scientists and environmentalists of the first Earth Day era.

When the continued existence of several species of whales was very much in doubt, people who are now friends and colleagues of mine worked tireless, hard-fought battles that achieved, in 1986, a global ban on most commercial whale hunting. Another of my friends was burned in effigy for her tireless work to secure regulations that would prevent the last sea turtles on the East Coast from drowning in shrimp nets.

But whales are now so common in our waters that it is no longer exceptional to see them from our ocean beaches. Sea turtle numbers have sky-rocketed from 1980s lows. Since the 1990s I’ve worked on several key campaigns to turn around the deep depletions in our fish populations and some of these, too, have worked beyond our — and our opponents’ — expectations.

Last summer, a friend told me of seeing several whales from the beach in East Hampton. He said they were feeding just beyond the surf on dense schools of herring-like fish called menhaden. Because they formerly existed in enormous schools, are very energy and nutrient rich, and are eaten by many kinds of fish, seabirds, and marine mammals, menhaden have been called “the most important fish in the sea.” And because of recent hard-won catch restrictions, they’ve been rapidly recovering.

The morning after I got my friend’s tip, I checked five beaches from Amagansett to the west side of East Hampton. To my astonishment, I saw whales, dolphins, and dense schools of menhaden at every stop. The next morning I took my boat around Montauk Point for a water view. I first encountered the menhaden schools just west of the Point. Millions of fish extended in an unbroken school twenty miles long, with a humpback whale or two lunging spectacularly into breakfast every mile and a half or so. I went as far west as Amagansett, traveling just beyond the surf. I took a bunch of photos and decided to head back, knowing that the fruits of these spectacular recoveries continued far down the beach.

Nature is under withering pressure worldwide. But we here on Long Island are beneficiaries of some of the best successes I know about. And the successes are both spectacular and instructive.

When we give natural communities and endangered species a break, and make the slightest accommodation to coexist and let life live, they strive to recover the abundance, vitality, and beauty of the original world. Two things are required: we have to want it, and a few people have to move a few obstacles and let it happen. And then we can have, and pass along, a more alive, more beautiful world. It can work.

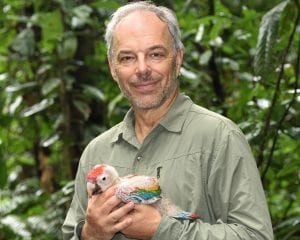

Carl Safina is an ecologist and a MacArthur Fellow. He holds the Endowed Chair for Nature and Humanity at Stony Brook University and is founder of the not-for-profit Safina Center. He is author of numerous books on the human relationship with the rest of the living world. Carl’s new book is “Becoming Wild; How Animal Cultures Raise Families, Create Beauty, and Achieve Peace.” More at CarlSafina.org and SafinaCenter.org