By Tara Mae

“It is the perfect job, but it is not work.”

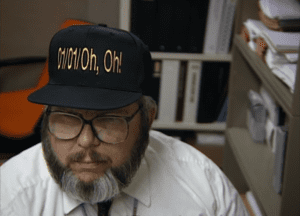

This is how Carol Parker describes her free weekly children’s Story & Craft, which she hosts on Mondays from 10:30 to 11:30 a.m., at The Next Chapter bookstore in Huntington.

Like any good grandmotherly figure, Nana Carol, as she is known, has a generosity and geniality to her that translates into her storytelling. Allaying any shyness and welcoming all who join her, Nana Carol strives to engage her temporary charges with warmth and wonder. Yet, Parker’s effervescent engagement is not without an outline and structure. Each session follows a loose schedule: gentle movement, spellbinding stories, and creative crafts.

“We begin with our little stretch…I lead them with a little rhyme: tall as a tree, wide as a house, thin as a pin, quiet as a mouse,” Parker, who lives in Huntington, said. “It sets the tone and they have gotten so good at it. All the kids are quite happy to sit down when I ask. We start a book, but I do not just read it, we talk as I read. As the story progresses, the children start out on carpet, then creep closer and closer.”

The attentive tykes move from their spots on the bookstore’s alphabet rug, stealthily moving forward until they are gathered around Parker, at her knee. Enrapturing them with an eclectic assortment of character voices, Parker puts her own touch on modern classics and old favorites.

Through these personifications, Parker shares stories that have a message. Her favorite books to read to the kids are from the Bad Seed series, written by John Jory and illustrated by Pete Oswald. They tell the story of a bad seed: ill-mannered and ill-tempered. Through the transformative power of will, acceptance, and personal growth, he is able to sprout a new attitude.

“I love those books…I ask them questions after every page, so they have a memory that coincides with what we are reading. Kids get what is going on; they become so excited and interact,” she said.

This aligns with Parker’s philosophy of providing the kids as well as their parents/caretakers with more than just story time: she encourages an interactive experience that ignites inceptive imaginations. Originally geared towards infants through four years old, Nana Carol wants to welcome kids of all ages to enjoy stories and a craft.

“Week to week is different since you never know the age of the kids in advance nor how long you can keep them interested,” Parker said. The average audience member’s attention span for active listening is about two books long, then it is craft time.

Crafts are primarily paper-based to limit mess and mayhem: no glitter allowed. Parker precuts the pieces and individually packs each craft in separate bags for each child. Activities have holiday and seasonal themes. In the fall, the children constructed autumnal wreathes and scarecrows.

Parker’s attention to detail extends to her craft supplies, which come from her personal collection. A couple of years ago, she found out that a nursery school was closing, and with the assistance of her daughter-in-law, rescued construction paper, markers, and other materials.

Well-versed in applying ingenuity as inspiration, Parker always plans the crafts, but may not select what to read until she is perusing the shelves of The Next Chapter.

An avid reader since her childhood in England — her favorite books were by English children’s writer Enid Blyton — as an adult, Parker’s tastes now gravitate towards the writings of Jodi Picoult, Kristin Hannah, and any works that cover World War II as a topic.

Parker, who came to the United States as a senior in high school, does not have many memories of being read to as a child. But, she has consistently sought to share her reverence of the written word with her kids and grandkids.

In fact it was this passion, and her frequent trips to a former local bookstore, that led to her popular moniker.

“Nana Carol came from taking my grandkids to Book Revue in Huntington all the time; the staff heard me being called ‘nana’ and just applied it to my first name,” Parker said.

Around 2018, when her grandchildren were a bit older, she volunteered her services for Book Revue’s story time. Nana Carol was an apparent natural with the bookstore’s youngest patrons, who quickly became enamored with her energy and emotional resonance.

The pandemic halted this progress; the ability to enrapture very young minds was lost in translation on Zoom. In 2021, unable to afford its rent, Book Revue closed.

What seemed like the end of a saga, was actually the start of a fresh narrative. Staff of Book Revue banded together to open The Next Chapter, and reached out to Parker, inviting her to join them in this new venture. She readily agreed, and together they have been building a literary legacy.

“They took donations of tables and chairs, set up little areas where you can sit and read; it is very homey. Book Revue was wide, The Next Chapter is long. Its’ set up is lovely,” Parker said. “On Saturdays they have a flea market in the parking lot, with artisans displaying personal crafts, artists showing art, etc. [The staff] is really trying to establish a destination like Book Revue used to be. They are so very good to me.”

And Parker is good their smallest clients. “I love kids and I love doing this…To make a child smile, make a child happy, that’s like a million dollar check to me,” she said.

The Next Chapter Bookstore is located at 204 New York Avenue in Huntington. For more information about Story & Craft with Nana Carol, other programs, and the bookstore itself, please visit www.thenextchapterli.com.

FILM SCHEDULE

FILM SCHEDULE