By Daniel Dunaief

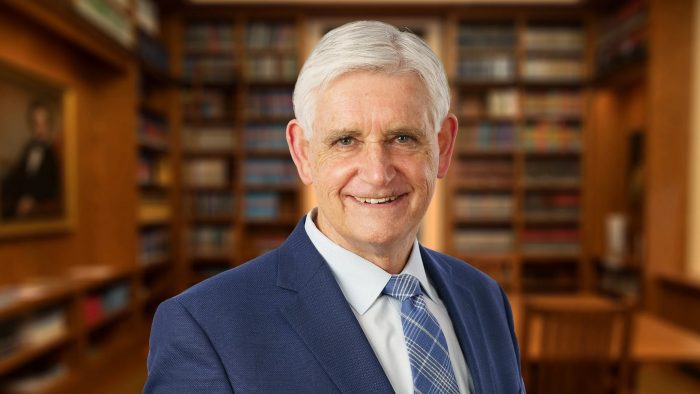

Richard McCormick wants more.

The interim president of Stony Brook University, whose tenure started in August and is set to end in June, wants more students, more buildings, more funding for science, more interdisciplinary collaborations and, to help make much of that possible, more money from the state.

In a recent celebrity spotlight podcast interview, McCormick shared a vision that addressed everything from identifying scientific priorities for the next decade, to adding sufficient wastewater treatment for proposed new buildings, to ensuring sufficient funding for student education and research.

McCormick, who has had more than four decades of experience in higher education, and said he is “enjoying this position more than any other I’ve had in my whole life,” is thinking well beyond June.

This winter, McCormick is asking New York State for $1.2 billion, split evenly over the course of the next four years, to add new buildings. He will also request additional funds to upgrade buildings with deferred maintenance.

“We’re seeking significant resources from the state of New York for deferred maintenance,” McCormick said. Stony Brook has an estimated $2 billion in deferred maintenance, including buildings that house the College of Business in Harriman Hall, the School of Social Welfare and the School of Dental Medicine.

“We also need new facilities, particularly interdisciplinary research facilities,” he added.

McCormick has shared a proposal, which SUNY Chancellor John King, Jr. supports, that seeks resources for these new interdisciplinary buildings on the West and East Campuses.

“It’s going to be my main focus of effort during the winter, to obtain support for that capital facilities plan,”said McCormick.

In addition to a request for buildings, the interim president will seek funds for an operating budget and staff that can support a larger student body.

This year’s freshman class of 4,040 students is the largest to date. That makes Stony Brook stand out amid the average decline of five percent in first year enrollment at universities and colleges across the country.

“We’re a hot school right now,” McCormick said, particularly after Stony Brook climbed the 2024 ranks of colleges in US News and World Report to 58th among national universities and 26th among public universities.

The operating budget for Stony Brook, which declined in the decade that ended in 2020, has been rising. “Another pitch I’ll be making in Albany during the legislative session will be to maintain that increase,” McCormick added. The higher budget will support limiting factors such as housing, wastewater, dining and faculty.

More faculty

Stony Brook has been adding faculty recently, and would like to ensure that any increase in student enrollment doesn’t affect class sizes. “The aim will be to keep the pace of faculty appointments in line with the growth of students,” McCormick said.

The interim president plans to continue to invest in research, as well. He is making more investments in shared facilities and equipment, is providing faculty with more support in applying for federal grants, and administering those grants, and is bolstering the high powered computing capacity such research demands. Those efforts are underway under the direction of Vice President for research Kevin Gardner, who also joined Stony Brook at the beginning of August.

New initiatives

At the same time, the interim president has added several new efforts.

He has appointed a task force that is charged with exploring opportunities for greater collaboration across Nichols Road. In addition, McCormick has convened a science futures committee that will come up with the developments the university should contribute to over the next decade.

He does not want to dictate this focus from the president’s office and is relying on this panel to “paint a bold picture of where science is going and what are the cutting edge fields Stony Brook should be investing in,” McCormick said. The group will share its vision in a public document.

McCormick is also bringing an effort he created when he was president at Rutgers University from 2002 to 2012. Called a Future Scholars Program, Stony Brook will identify about 100 students in five Southampton School Districts, who will be entering eighth grade next fall.

“We are going to put our arms around them, promise to support them with peer tutoring and mentoring, and with academic visits during the summer or the year,” he said.

In addition to ensuring that these students take college prep courses, Stony Brook will promise these students that “if you get a C in your math course, you’re going to get a call from us and you’re not going to get another C in math.” For students in this program who gain admission to Stony Brook on their merits, the university promises free tuition.

The Southampton schools are working on the process to identify these students. In the following year, the future scholars will come from five schools in the Stony Brook area. The primary criteria to find these students is promise and not grades.

A college town

McCormick would also like to develop a college town with businesses like pizza restaurants and bars.

This could be on the campus side of the railroad station and would be conceived of and created in collaboration with the private sector. The idea, he suggested, is to create a commercial district that’s within easy walking distance and which is particularly receptive to college students. McCormick would want those places to be “student friendly in every sense of the word, including their hours of operation,” he added. This, like some of his other ideas, is a longer term project that wouldn’t be completed within a year.

Concerns

McCormick shared several concerns in connection with Stony Brook and higher education.

He mentioned his worry about any future cuts in financial aid either for students in need or for scientific research. “It would be very, very hurtful not just to Stony Brook but to every university of our kind if there were significant reductions in student support or support for ongoing research, so we’re keeping an eye on that,” he said. When he speaks to members of Congress, he plans to discuss the importance of basic research, which can lead to advancements in health care and economic growth.

The interim president also believes in creating opportunities for talented students who come from a wide range of experiences and backgrounds. He recognizes that diversity, equity and inclusion efforts have become a political hot button. Still, he is not going to give up on opportunities for men and women to get college educations.

He also recognizes that some students are undocumented immigrants. “We want to do everything we can to protect our students,” he said. While he believes none of these threats are imminent, he plans to remain vigilant.

As a history professor who, at one point, taught a class jointly with his father at Rutgers, McCormick hopes and prays the country can become reunited amid heated rancor. He sees the lead up to the Civil War as the closest historical parallel to the current climate.However, McCormick does not anticipate that history will repeat itself.

Despite the tension, he remains optimistic about the future of the United States based on his faith in the country.

Next president

When Stony Brook tapped McCormick as its interim president, he indicated that he would not be a candidate for the permanent role. Indeed, the announcement of his role indicated he would have this position only through June 2025.

“I agreed to that,” McCormick said. “I signed that letter,” indicating that he wouldn’t be a candidate.

Still, he would be willing to stay on as president, if that opportunity arose.

Based on his experience at Stony Brook, where he has found the culture warm, receptive and supportive, he would like to see the next president, no matter who it is, “be a nice person.”

“It is absolutely critical to the culture.”