By Daniel Dunaief

While many people are fortunate enough to ignore Covid or try to put as much distance between themselves and the life altering pandemic, others, including people throughout Long Island, are battling long Covid symptoms that affect the quality of their lives.

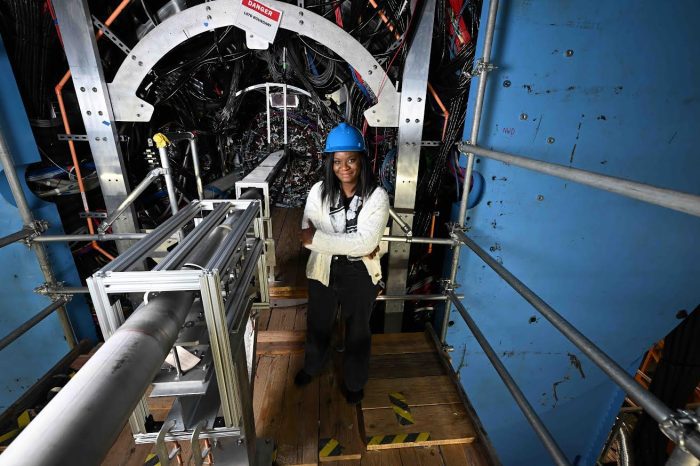

Photo from Stony Brook Medicine/Jeanne Neville

Sritha Rajupet, Director of the Post-Covid clinic at Stony Brook Medicine and Chair of Family, Population & Preventive Medicine, puts her triple-board certified experience to work in her efforts to provide relief and a greater understanding of various levels of symptoms from Covid including pain, brain fog, and discomfort.

Rajupet serves as co-Principal Investigator, along with Dr. Hal Skopicki, chief of cardiology and co-director of the Stony Brook Heart Institute, on a study called Recover-Autonomic.

This research, which uses two different types of repurposed treatments that have already received Food and Drug Administration approval in other contexts, is designed to help people who have an autonomic nervous system disorder called Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome. People with this syndrome typically have a fast heart rate, dizziness or fatigue when they stand up from sitting down.

Stony Brook is contributing to a clinical trial for two different types of treatments, each of which has a control or placebo group. In one of the trials, patients receive Gamunex-C intravenous immunoglobulin. In the other, patients take Ivabradine by mouth.

Stony Brook has been enrolling patients in this study since the summer. The intravenous study is a nine-month trial.

Some improvements

Dawn Vogt, a 54-year-old Wading River resident, is enrolled in the intravenous trial.

While Vogt, who has been a patient of post Covid clinic since November of 2022, doesn’t know whether she’s getting the placebo or the intravenous treatment, she has been feeling better since entering the study.

The owner of a business called Office Solutions of Long Island, Vogt has been struggling for years with body aches, headaches, fever, stomach pain, fatigue and coughing.

“I’m definitely feeling better,” said Vogt, whose Covid fog can become so arduous on any given day that she struggles with her memory and her ability to put words together, as well as to engage in work that required multitasking.

“I’m a big puzzle person,” said Vogt. “[After Covid] I just couldn’t do it. It was and still is like torture.”

Still, Vogt, who was earning her undergraduate degree in women and gender studies at Stony Brook before she left to deal with the ongoing symptoms of Covid, feels as if several parts of her treatment, including the clinical trial, has improved her life.

Since her treatment that started during the summer, she has “definitely seen improvement,” Vogt said.

In addition to the clinical trial, Vogt, who had previously run a half marathon, received a pace maker, which also could be improving her health. “I’m starting to have more energy, instead of feeling exhausted all the time,” she said, and has seen a difference in her ability to sleep.

Vogt feels fortunate not only for the medical help she receives from Rajupet and the Stony Brook clinic, but also for the support of her partner Tessa Gibbons, an artist with whom Vogt developed a relationship and created a blended family in the years after Vogt’s husband died in 2018.

“My hope is that I can find a new normal and that I can become functional so that I can get back to doing some of what I love,” she said.

Vogt urges others not to give up. “If your doctors don’t believe you, find one who does,” she said. “My doctors at Stony Brook, including Dr. Rajupet and the whole team, are amazing. They listened, they are compassionate and they don’t ever say, ‘That’s crazy.’”

Indeed, in working with some of the over 1,500 unique patients who have come to Stony Brook Medicine’s post-Covid clinic, Rajupet said she “explores things together.” When her patients learn about something new that they find through their own research, she couples that knowledge with her own findings to develop a treatment plan that she hopes offers some comfort and relief.

Ongoing medical questions

Doctors engaged in the treatment of long Covid are eager to help people whose quality of life can and often is greatly diminished.

People “haven’t been able to work, haven’t been able to do activities they enjoy whether that’s sports as a result of their fatigue or myalgia [a type of muscle pain]. Concentration may be affected, as people can’t read or perform their work-related activities,” said Rajupet.

At this point, long Covid disproportionately affects women.

During her family medicine residency, Rajupet learned about preventive medicine in public health. She worked with specific populations and completed an interdisciplinary women’s health research fellowship.

Her research background allowed her to couple her primary care experience with her women’s health background with a population approach to care.

The Stony Brook doctor would like to understand how many infections it takes to develop long Covid.

“For some, it’s that one infection, and for others, [long Covid] comes in on the third or fourth” time someone is battling the disease, Rajupet said.

She also hopes to explore the specific strains that might have triggered long Covid, and/ or whether something in a person’s health history affected the course of the disease.

Rajupet recognizes that the need for ongoing solutions and care for people who are managing with challenges that affect their quality of life remains high.

“There are still 17 million people affected by this,” she said. “We have to make sure we can care for them.”

As for Vogt, she is grateful for the support she receives at Stony Brook and for the chance to make improvements in a life she and Gibbons have been building.

Her hope is that “every day, week, month and even hour, I take one more breath towards being able to function as best as possible,” Vogt said. “My goal is to live the best life I can every day.”