By Daniel Dunaief

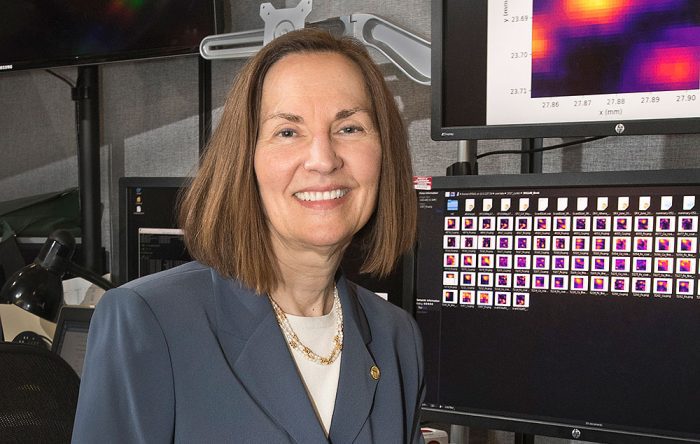

To borrow from the show Hamilton, Ellen Pikitch was in the room where it happens.

The Endowed Professor of Ocean Conservation Science at Stony Brook University, Pikitch traveled to the United Nations on the east side of Manhattan last month to serve as a delegate for Monaco during the Preparatory Commission for the High Seas Treaty, which is also known as Biodiversity Beyond National Jurisdiction.

The meeting, the first of several gatherings scheduled after the passage of the historic High Seas Treaty that is designed to protect 30 percent of the oceans by 2030, started to create a framework of rules and procedures.

Pikitch, who has advanced, developed and implemented Marine Protected Areas globally, was pleased with the early progress.

“I came away feeling optimistic that we are going to have a functional High Seas Treaty within a couple of years,” said Pikitch. “These details are being hashed out before the treaty comes into force.”

Indeed, 60 nations need to ratify the treaty for it to come into force.

At this point, 20 of the 194 countries that are member state of the United Nations have ratified the treaty. Each country has its own procedures for providing national support for an effort designed to protect biodiversity and natural resources.

Numerous representatives and members of environmental organizations are encouraging leaders of countries to ratify the treaty before the United Nations Oceans conference in Nice from June 9th to June 13th.

Award winning actress and activist Jane Fonda gave a speech at the meeting, urging countries to take the next steps.

“This isn’t just about protecting the oceans. It’s about protecting ourselves,” said Fonda. “Please, please, when you go back to your capitals in the next few days, remind your ministers of what we’re working toward. Remind them that we have a chance this year to change the future.”

Getting 60 ratifications this year is going to be “another monumental achievement,” Fonda continued. “We know it isn’t easy, but we also know that without the level of urgency… the target of protecting 30 percent of the world’s oceans will slip out of our grasp.”

Pikitch expects that the first 60 countries will be the hardest and that, once those agree, others will likely want to join to make sure they are part of the decision making. The treaty will form a framework or benefit sharing from biodiversity discovered as well as the resource use and extraction at these high seas sites.

“New discoveries from the high seas are too important for countries to ignore,” Pikitch said.

The members who ratify the treaty will work on a framework for designating protected areas on the high seas.

Pikitch shared Fonda’s sense of urgency in advancing the treaty and protecting the oceans.

“There is no time to waste,” Pikitch said. In the Stony Brook Professor’s opinion, the hardest part of the work has already occurred, with the long-awaited signing of the treaty. Still, she said it “can’t take another 20 years for the High Seas Treaty to come into effect.”

Monaco connection

Pikitch has had a connection with the small nation of Monaco, which borders on the southeastern coast of France and borders on the Mediterranean Sea, for over a decade.

Isabelle Picco, the Permanent Representative to the United Nations for Monaco, asked Pikitch to serve as one of the two delegates at the preparatory commission last month.

Pikitch is “thrilled” to be working with Monaco and hopes to contribute in a meaningful way to the discussion and planning for the nuts and bolts of the treaty.

Other meetings are scheduled for August and for early next year.

Most provisions at the United Nations require unanimous agreement, which, in part, is why the treaty itself took over 20 years. Any country could have held up the process of agreeing to the treaty.

To approve of a marine protected area, the group would only need a 2/3 vote, not a complete consensus. That, Pikitch hopes, would make it more likely to create a greater number of these protected places.

Scientific committee

The meeting involved discussions over how the treaty would work. Once the treaty has come into force, a scientific committee will advise the secretariat. The group addressed numerous issues related to this committee, such as the number of its members, a general framework for how members would be selected, the composition of the committee in terms of geographic representation, how often the committee would meet and whether the committee could set up working groups for topics that might arise.

Representatives of many countries expressed support for the notion that the scientific committee would make decisions based on their expertise, rather than as representatives of their government. This approach could make science the driving force behind the recommendations, rather than politics, enabling participants to use their judgement rather than echo a political party line for the party in power from their country.

Several participants also endorsed the idea that at least one indigenous scientist should be on this committee.

Pikitch, who has also served at the UN as a representative for the country of Palau, was pleased that the meeting had considerable agreement.

“There was a spirit of cooperation and a willingness to move forward with something important,” she said. By participating in a timely and meaningful way in this process, [the countries involved] are behaving as though they are convinced a high seas treaty will come into force” before too long.

Ultimately, Pikitch expects that the agreement will be a living, breathing treaty, which will give it the flexibility to respond to fluid situations.

As Fonda suggested, the treaty is about “recognizing that the fate of humanity is inextricably linked to the health of the natural world.” She thanked the group for “giving me hope.”