By Daniel Dunaief

Eating machines even more focused than teenagers approaching a stocked refrigerator, snakes slither towards foods other animals assiduously avoid.

In a recent and extensive study of snakes using the genetics, morphology and diet of snakes that included museums specimens and field observations, a team of scientists including Pascal Title, Assistant Professor in the Department of Ecology & Evolution at Stony Brook University, showed that the foods skin-shedding creatures eat as a whole is much broader than the prey other lizards consume.

At the same time, the range of an individual snake’s diet tends to be narrower, marking individual species as more specialized predators, a paper recently released for the cover of the high-profile journal Science revealed.

“If there is an animal that can be eaten, it’s likely that some snake, somewhere, has evolved the ability to eat it,” Dan Rabosky, senior author on the paper and curator at the Museum of Zoology and Professor of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology in the College of Literature, Science and the Arts at the University of Michigan, explained in a statement.

The research, which explored the genetics and diets of snakes, suggested that snakes evolved up to three times faster than lizards, with shifts in traits associated with feeding, locomotion and sensory processing.

“This speed of evolution has let them take advantage of new opportunities that other lizards could not,” Rabosky added. “Fundamentally, this study is about what makes an evolutionary winner.”

No singular physical feature or characteristic has enabled snakes to specialize on foods that are untouchable to other animals.

“It seems to be a whole suite of things” that allows snakes to pursue their prey, Title speculates.

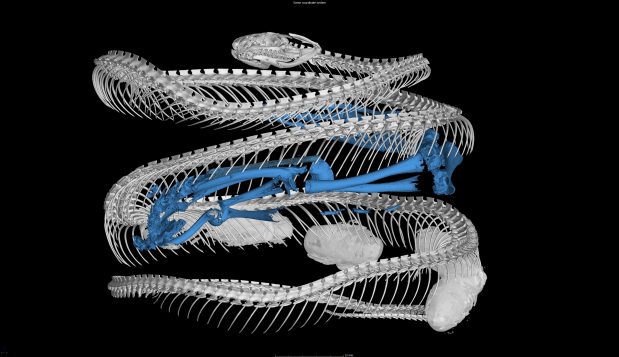

One unique aspect of many advanced snakes is that they have more mobile elements in their skulls. Rock pythons can stretch their jaw around enormous prey, making it possible for them to swallow an entire antelope. Garter snakes, meanwhile, can eat Pacific newts that have a high concentration of a neurotoxin. Snakes also can eat slugs and snails that have evolved a defensive ability to secrete toxins.

A change to textbooks

Title, who is the co-lead and first author on the paper, suggested that the comprehensive analysis of snakes, particularly when compared with lizards, will likely change the information that enters textbooks.

“I think the analysis of lizard and snake diets in particular could potentially enter herpetology textbooks because diet is such a fundamental axis of natural history and because the visuals are so clear,” Title said. He doesn’t believe an analysis of dietary resolution that encompasses snakes and lizards has been shown like this before.

With a few exceptions, the majority of lizards eat terrestrial arthropods. Snakes have expanded into eating not only invertebrates, but also aquatic, terrestrial and flying vertebrates.

“They have absolutely evolved the ability to prey on semi-aquatic and aquatic prey,” said Title.

Title and his collaborators gathered considerable amounts of sequence data from GenBank. They also collected data from samples and specimens in the literature.

“Our dataset involves specimen-based data from museum collections that span the globe over the better part of the last century,” he explained.

The project started with the realization that several authors were generating high-quality sequence data for separate projects from biodiversity hotspots for lizards and snakes, such as in Australia, Brazil and Peru. The researchers realized that combining their data provided unprecedented coverage.

After Title completed his PhD at the University of Michigan, he took a leading role in building the phylogeny and conducting many of the analyses.

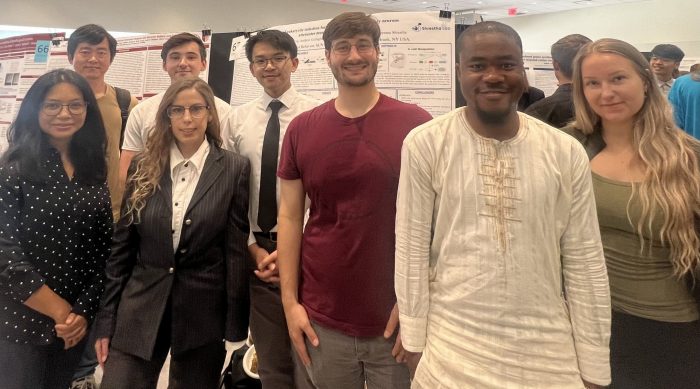

Indeed, the list of coauthors on this study includes 19 other scientists from the United States, the United Kingdom, Australia, Brazil and Finland.

As for his work, Title is broadly interested in the ecological/ environmental/ geographic/ evolutionary factors that lead to different species richness. He is not restricted to lizards and snakes.

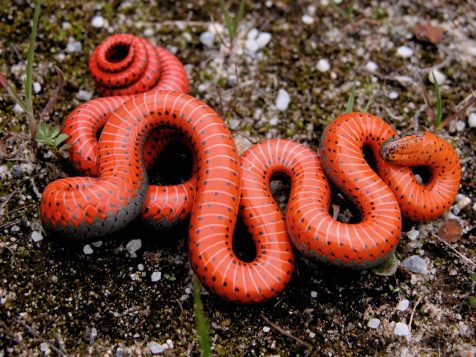

“I do think snakes are unbelievable,” he said. “I’ve seen sidewinder rattlesnakes flip segments of their body forward across the sand in California, I’ve seen snakes climb straight up trees and walls, I’ve seen long, skinny snakes carefully navigate tree branches, and I’ve seen semi-aquatic snakes swim with their head above water. It’s mesmerizing.”

‘Snakes are cool’

Co-lead author Sonal Singhal, Assistant Professor in Biology at California State University, Dominguez Hills, met Title when she was a PhD student and he was an undergraduate at the University of California, Berkeley.

Singhal is excited that readers can “learn cool facts about snakes from our paper,” she explained. “Research papers don’t always inspire a sense of wonder in the reader.” She hopes people “walk away from this study thinking that snakes are cool.”

Singhal suggested that Title is leading a group of collaborators to create a package that will enable other researchers to download the data from this paper quickly and easily and use it in their own work.

As a whole, snakes are moving around in their diet space at a much more rapid clip than lizards in general, Title suggested.

While snakes have evolved rapidly over short periods of time, it’s unclear how these creatures are responding to changes in the environment on smaller time scales, such as through what’s currently occurring amid climate change.

The scale, Title explained, is different, with climate changes affecting the world over decades and centuries, while snake evolution, particularly regarding specialized diets, transpired over the course of millions of years.

Grad school encounter

Title, who lives in East Setauket, met his wife Tara Smiley when both of them were graduate students.

An Assistant Professor in the Department of Ecology & Evolution at Stony Brook University, Smiley is a paleoecologist specializing in small mammals.

The couple enjoys taking their son Micah, who is almost three years old, on camping trips and spending time outdoors.

As for the paper scoring the coveted spot on the cover of Science, Title suggested the exposure validates “that lizards and snakes, and their natural history, are inherently intriguing to all sorts of people, regardless of whether or not they are trained biologists.”

He hopes the work will not only inspire young scientists to learn more about snakes and lizards, but also to seek to quantify and explore the different axes of biodiversity and to “appreciate the value of supporting natural history museum collections.”

———————————————————————————–Within a day of snake research published on the cover of Science last week, reports surfaced about the discovery of what may be the largest snake in the world. Scientists from the University of Queensland found a northern green anaconda in the Ecuadorian Amazon that was close to 21 feet long.

Pacal Title, Assistant Professor in the Department of Ecology & Evolution at Stony Brook University and first author on the recent Science paper, offered his thoughts in an emailed question and answer exchange about the anaconda, which was not a part of his recent research.

TBR: Is this a particularly compelling find?

Title: This is compelling as it provides an example of broadly distributed, large species of snakes having pretty significant genetic differentiation. There are quite a few examples, both within snakes and in other groups, where populations look superficially similar, but turn out to have been genetically independent of one another for quite a long time.

TBR: How does a discovery of what might be the largest snake in the world fit into the context (if at all) of your research? Does this species validate the radiative speciation you described?

Title: It shows that the number of known snake species is likely to be an under-estimate, although this is likely to be true for most groups out there. This fits well into the perspective that snakes have incredibly high global species diversity.

TBR: Do you have any guesses as to what the diet of this snake could be?

Title: The article describes anaconda diets as generally consisting of terrestrial vertebrate prey, despite the species being semi-aquatic.

TBR: What, if any, predators might pursue this snake?

Title: Jaguars have been known to prey on anacondas.

TBR: What scientific, life history, genetic or other questions would you address, if any, about this species?

Title: Now that the green anaconda is being considered as two separate species, all morphological, ecological and natural history attributes will need to be re-examined to evaluate whether or not the two species actually differ along any of these axes.

TBR: Is the ongoing attention snakes receive positive for the study of snakes?

Title: It is great that snakes are receiving positive attention. Such new studies are essential for conservation, and for the study of biodiversity and ecosystems.