By Daniel Dunaief

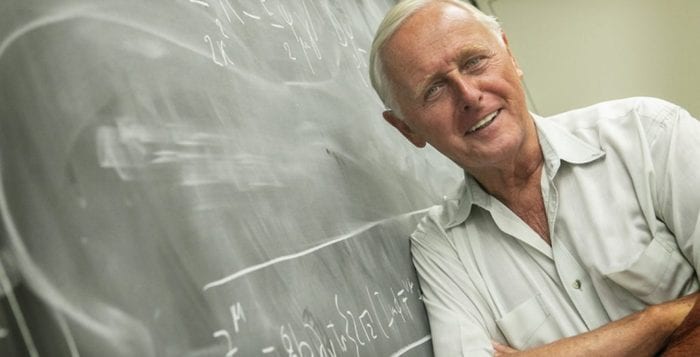

Peter van Nieuwenhuizen was sitting at the kitchen table, paying an expensive dental bill, when he received an extraordinary phone call. After he finished the conversation, he shared the exciting news — he and his collaborators had won a Special Breakthrough Prize in Fundamental Physics for work they’d done decades earlier — with his wife, Marie de Crombrugghe.

The prize, which is among the most prestigious in science, includes a $3 million award, which he will split with Dan Freedman, a retired professor from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Stanford University, and Sergio Ferrara from CERN.

De Crombrugghe suggested he could use the money “for a whole new set of teeth,” if he chose.

Van Nieuwenhuizen, Freedman and Ferrara wrote a paper in 1976 that extended the work another famous physicist, Albert Einstein, had done. Einstein’s work in his theory of general relativity was incomplete in dealing with gravity.

Freedman, who was at Stony Brook University at the time, van Nieuwenhuizen and Ferrara tackled the math that would provide a theoretical framework to include a quantum theory of gravity, creating a field called supergravity.

After 43 years, “I didn’t expect” the prize at all, said van Nieuwenhuizen. It’s not only the financial reward but the “recognition in the field” that has been so satisfying to the physicist, who continues to teach as a Toll Professor in the Department of Physics at SBU at the age of 80.

“To have one’s work validated by great leaders has just been wonderful,” added Freedman, who worked at SBU through the 1980s until he left to join MIT. He treasures his years at Stony Brook.

Freedman believes a seminal trip to Paris, where he discussed formative ideas that led to supergravity with Ferrara, was possible because of Stony Brook’s support.

The physics trio approached the problem of constructing a way to account for gravity by combining general relativity and particle physics, which were in two separate scientific communities at the time. Even the conferences between the two types of physics were separate.

Einstein’s theory of general relativity has infinities when scientists add quantum aspects to it. As a result, it becomes an inconsistent theory. “Supergravity is not a replacement of Einstein’s theory, it is an extension or a completion if one is bold,” van Nieuwenhuizen explained.

The Stony Brook professor suggested that supergravity is an extension of general relativity just as complex numbers are an extension of real numbers. He added that it’s unlikely that there are other extensions of general relativity that theoretical physicists have yet to postulate.

Supergravity is “confirmed by its finiteness,” he said, adding that it suggests the existence of a gravitino, which is a partner to the graviton or the gravity-carrying boson. At this point, scientists haven’t found the gravitino.

“Enormous groups have been looking” for the gravitino, but, so far, “haven’t found a single one,” van Nieuwenhuizen said. The search for such a particle isn’t a “problem for me. That’s what experimental physicists must solve,” he said.

The work has already had implications for numerous other fields, including superstring theory, which attempts to provide a unified field theory to explain the interactions or mechanics of objects. Even if the search for a gravitino doesn’t produce such a particle, van Nieuwenhuizen suggested that supergravity still remains a “tool able to solve problems in physics and mathematics.”

Indeed, since the original publication about supergravity, over 11,000 articles have supergravity as a subject.

Collaborators and fellow physicists have reached out to congratulate the trio on winning the Special Breakthrough Prize, which counts the late Stephen Hawking among its previous winners.

The theoretical impact of supergravity “was huge,” said Martin Roček, a professor in the Department of Physics at Stony Brook who has known and worked with van Nieuwenhuizen for decades.

Whenever interest in the field wanes, Roček said, someone makes a new discovery that shows that supergravity is “at the center of many things.”

He added that the researchers are “very much deserving” of the award because the theory “offers such a rich framework for formulating and solving problems.”

Roček, who worked as a postdoctoral researcher in Hawking’s laboratory, said other researchers at Stony Brook are “all delighted” and they “hope some of the luster rubs off.”

Van Nieuwenhuizen’s legacy, which is intricately linked with supergravity, extends to the classroom, where he has invested considerable time in teaching.

Van Nieuwenhuizen is a “wonderful teacher,” Roček said. Indeed, he received the Dean’s Award for Excellence in Graduate Teaching in 2010 based on teaching evaluations from graduate students. Roček has marveled at the way van Nieuwenhuizen prepares for his lectures, adding, “He doesn’t give deep statements and leave you bewildered. He explains things explicitly and he does a lot of calculations without being dull.”

Van Nieuwenhuizen recalled the exhilaration, and challenge, that came from publishing their paper in 1976. “We knew right away” that this was a seminal paper, he said. “The race was on to discover its consequences.”

Prior to the theory, the three could work in relative calm before the physics world followed up with more research. After their discovery, they knew the “happy, isolated life is over,” he said..

Van Nieuwenhuizen has no intention to retire from the field, despite the sudden funds from the prize, which is sponsored by Sergey Brin, Priscilla Chan, Mark Zuckerberg, Pony Ma, Yuri and Julia Milner and Anne Wojcicki.

“The idea that I would stop abhors me,” he said. “I wouldn’t know what on earth I would be doing. I consider it a privilege to give these courses, to work and be paid to do my hobby. It’s really unheard of.”

O’Leary suggested that the paper provides some context for climate and sea level changes that can and have occurred. During the period she studied, the Earth was considerably warmer, with over 40 percent of today’s exposed land covered by water. Sea levels were about 300 meters higher than current levels, although the Earth wasn’t home to billions of humans yet or to many of the modern day species that share the planet’s resources.

O’Leary suggested that the paper provides some context for climate and sea level changes that can and have occurred. During the period she studied, the Earth was considerably warmer, with over 40 percent of today’s exposed land covered by water. Sea levels were about 300 meters higher than current levels, although the Earth wasn’t home to billions of humans yet or to many of the modern day species that share the planet’s resources. O’Leary said that much of the literature for the science in Mali was in French, which had kept it a bit below the radar for scientific discourse, which tends to be in English.

O’Leary said that much of the literature for the science in Mali was in French, which had kept it a bit below the radar for scientific discourse, which tends to be in English.