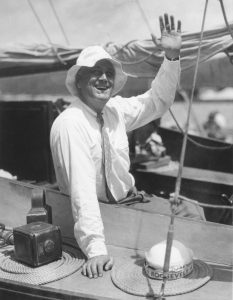

“The present situation is to be regarded as one of opportunity for us and not of disaster. There will only be cheerful faces at this conference table.” — Dwight D. Eisenhower, supreme allied commander

Approaching the middle of December 1944, the allied powers in Europe pushed back the German forces practically to their own border. The allies landed at Normandy in France on June 6, 1944, also known as D-Day, and this successful invasion established the beginning of the end of Hitler’s rule in Western Europe.

While the fighting was brutal on the beaches and later through the dangerous terrain of the hedge groves, under the leadership of Eisenhower and the armored drive of Gen. George Patton, the Germans took extremely high losses.

There was absolute joy on Aug. 19 when allied forces rolled through the streets of Paris, where they were greeted with loud cheers of freedom.

The once victorious German army was reeling after several battlefield losses, and by December 1944 the allies were about to enter this Axis nation. The others were Italy and Japan.

With the Soviet Union liberating their own territory and pushing into Eastern Europe, there was no respite within any part of the German frontlines, and during the night and day allied air crews strategically bombed German factories, resources, transportation, weapons and troop movements.

“Total war” brought the realization that the German military had no chance to win this war and that the end was near.

Eisenhower’s “broad front” campaign moved allied armies from the English Channel to the Swiss border. It was the confident belief among western forces that the German war machine would surrender within the face of defeat.

Operation Autumn Mist was the last major military offensive that Hitler waged against the allies, to attempt to drive a wedge between the western armies, with the goal of regaining the Belgian port of Antwerp. If the Germans could strike a powerful blow against the allies, Hitler mistakenly believed that the West would possibly agree to a peace, and Germany would turn its full attention to fighting the Soviet Union.

As the Germans were attacked from every direction, they organized 250,000 soldiers from 14 infantry divisions guarded by five panzer divisions. This surprise assault was a dangerous breakdown of allied intelligence. The Germans broke through the Ardennes Forest in southeast Belgium and hit allied positions that were in Belgium, France and Luxembourg.

There were only 80,000 allied soldiers who were shocked by this assault, and thousands were taken as prisoners of war. The Germans penetrated their armies against the American forces that still wore summer uniforms and had little ammunition.

Eisenhower was just promoted to his fifth star as General of the Army, and expected to travel to Versailles, France, to attend the wedding of his orderly Mickey McKeogh.

It was an attack that struck at the nerve of the broad front that was mostly held by American forces which faced shortages in reinforcements and resources. Brig. Gen. Anthony McAuliffe was demanded by his German counterpart that he surrender the 101st Airborne Division at Bastogne, Belgium. It did not help McAuliffe that the weather conditions were extremely poor, and American airplanes were briefly unable to provide air support and the ability to drop food and ammunition. As Bastogne was considered to be located at strategic crossroads, Eisenhower ordered that this town must be held at all costs by the 101st Airborne Division.

A famous victory

On Dec. 19, Eisenhower held a vital meeting with his key generals to contain and destroy this attack. His longtime friend Patton stated that he was able to disengage from his own battle, and push in force to assault the German armies to relieve the pressure that was placed on Bastogne.

Eisenhower counted on the battlefield drive of Patton and sought the general’s Third Army to relieve Bastogne and to make the Germans pay for this surprise attack. Both senior officers were old friends and Eisenhower looked at the irony of receiving the new senior rank and observed, “George, every time I get promoted, I get attacked.” Patton responded to his boss, “Yes, and every time you get attacked, I bail you out.”

During a time of brief defeat, this battle showed the true spirit of the American soldier and officer to overcome the burdens of bad weather and surprise of the German assault to achieve a great victory.

The Battle of the Bulge posed the serious problem of German spies who landed behind American lines and were dressed as American military police officers. The enemy changed and destroyed road signs, and were believed to be searching for Eisenhower, Patton and Gen. Omar Bradley.

American soldiers started using challenging passwords that focused on former World Series games, movie stars and political leaders to determine if an unknown soldier was possibly a spy. The German troops acted with total disregard toward the prisoners of war that had fallen into their hands.

Near the Belgian town of Malmedy, SS Lt. Col. Joachim Peiper was the head of the “Adolph Hitler” Division and ordered his soldiers to brutally kill 84 Americans within an open field.

Word quickly spread about these atrocities, and this motivated Americans to hold their ground against the unrelenting pressure of the German army.

At Verdun in northeast France, Eisenhower ordered Patton to take additional time to gain enough men and materials, and to make his first strike against the enemy a powerful one. With his soldiers and through the snow, Patton led the American Army through one of the largest battles ever fought by this nation. Although Patton previously warned about the possibility of an attack of this nature, he was determined to destroy the German army that was now in the open.

American forces began their pursuit to relieve the beleaguered garrison at Bastogne and to inflict casualties on Hitler’s last-ditch attempt to gain a victory in the west. The German high command envisioned a successful plan that would see their forces reach the French Meuse River, but they did not count on the 500,000 American soldiers that destroyed this plan.

Through a blizzard that created awful weather conditions, there were a reported 15,000 cold weather injuries and ailments that were created pneumonia, frostbite and trench foot.

New York Yankee Ralph Houk, rose from the rank of private to major during World War II and fought in the Battle of the Bulge. This catcher was decorated with the Purple Heart, Silver Star and Bronze Star for valor in service.

During this fight, Houk’s leadership prevented a major attack from over 200 enemy soldiers and five Tiger tanks. He was later ordered to take a jeep and a letter with vital intelligence to the beleaguered town of Bastogne. During his way through enemy lines, Houk was wounded in the leg. After this battle, he was almost killed when a German bullet traveled through his helmet.

Houk was later manager of the Yankees which won the 1961 World Series with Mickey Mantle, Roger Maris and D-Day World War II veteran Yogi Berra. Houk’s Yankees won the World Series again in 1962. He always said he was fortunate to survive the Battle of the Bulge.

The fighting lasted until Jan. 25, 1945, with the heavy cost of 19,000 Americans killed, 47,500 wounded and 23,000 captured or missing in action.

British Field Marshal Bernard Law Montgomery took credit for rescuing the American military during the height of the Battle of the Bulge. Monty. as he was known, was one of the most difficult leaders that Eisenhower had to manage as supreme commander of allied forces.

British Prime Minister Winston Churchill fully realized that the United States provided the vast majority of soldiers and weaponry into the war in Northwestern Europe. About this failed German offensive, he said, “This is undoubtedly the greatest American battle of the war and will, I believe, be regarded as an ever-famous American victory.”

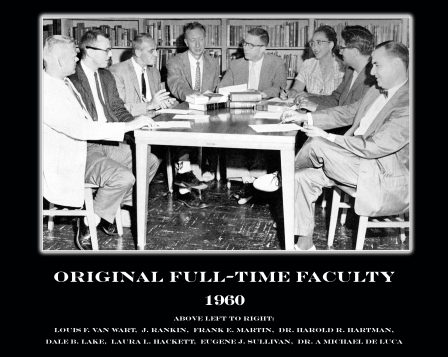

Rich Acritelli is a history teacher at Rocky Point High School and adjunct professor at Suffolk County Community College. Sean Hamilton, president of the high school history honor society, contributed to this article.