By Daniel Dunaief

A heaviness hovers in the air as we prepare to pack our daughter’s stuff into the car and drive her back to college, an environment fraught with new rules and anxiety. We realize this experiment in campus life, such as it is, might end in days or even a few weeks, as her school may pull the same rip chord it used in March.

While she is returning to campus, all but one of her classes is remote. The in-person class meets twice a week, so she is going back to a restricted college life for two hours a week of in-person learning.

Last year, with its jumble of emotions from taking her to college for the first time, seems so wonderfully innocent and low stress by comparison.

By taking her to college this week, she is already arriving on campus three weeks after classes began and is scheduled to return home before Thanksgiving. That means she’ll be on campus, at most, for two and a half months. That is two weeks longer than summer camp.

We want her to learn, have fun, meet new people and take advantage of college opportunities. Taking these goals one at a time, I’m not convinced that remote classes in which professors record lectures students can watch at their leisure provides the ideal academic experience.

How can they ask questions? How can they turn to the person sitting next to them, or, in the modern world, six seats away, and ask to repeat what they didn’t hear or to see if the professor might have misspoken?

College learning occurs on and off campus. In an ideal world, students not only learn from their professors and teaching assistants, but also from each other. They form study groups where they share notes and test each other.

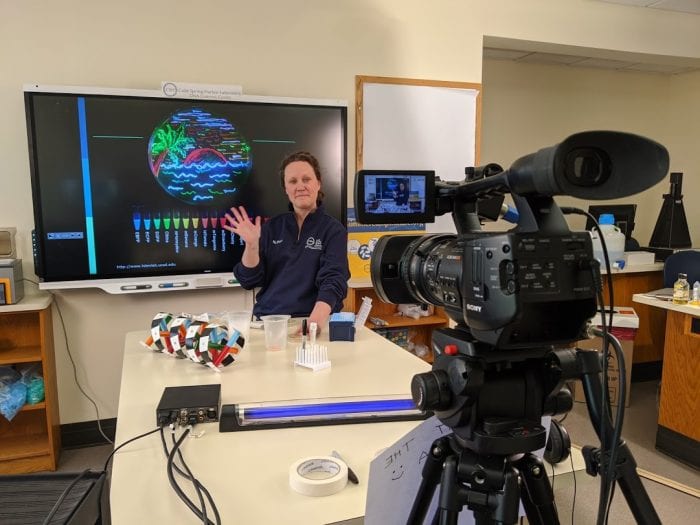

They could share their screens and form virtual study groups. In these small groups, however, they can and do send private chats to other people and feel freer to respond to the beep or flash of light on another electronic device, distracting them from the group exercise.

The personal connection through the computer is also limited, as people can’t slap each other on the back or chase each other around a library during a much-needed break.

We also want her to have fun, which isn’t the top priority for schools desperate to stay alive financially while keeping the campus community healthy. Even with the most active measures to protect everyone, the virus finds ways to evade detection and to spread.

The virus has become the boogeyman of our childhood nightmares, but instead of lurking under the bed or in dark corners of the closet, it waits on door knobs, in airborne particles and on banisters.

To protect everyone, the school isn’t allowing students to visit other dorms. They are limited in social gatherings outside, where they have to be six feet apart and also need to wear masks.

In a recent email, my daughter’s school told her, “If you see something, say something.” Those words, which became the cultural norm after 9/11, suggest that careless students are the equivalent of viral terrorists. Perhaps a better approach would be to encourage students to model safe behavior and to protect themselves and others on campus.

To facilitate safer social interactions, schools might consider putting up tents, in which they place small circles on the floor that are six feet apart. Students could visit each other in these settings, where they can talk and laugh and see each other in person and wear that great blouse or cool shirt that doesn’t look as good on zoom.

Ultimately, the opportunities they have will depend on the ability of the school, working with students, to figure out what they can do and not what they can’t or shouldn’t. We hope the challenges and adversity of the current reality somehow bring our daughter figuratively closer to her new friends, at a safe social distance.