By Daniel Dunaief

The wildfires last week in Quebec, Canada, that brought an orange haze, smoke and record pollution to New York were not only disconcerting, but also were something of a reality check.

These raging fires occurred earlier than normal and, with a so-called cut-off low in Maine acting like a bumper in a pinball game driving the smoke down along the eastern seaboard, created hazardous air quality conditions from New York through Virginia.

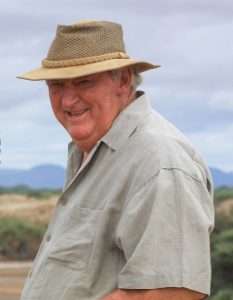

“There’s a real concern about this intensity, the size of the fire, happening this early in the season,” said Allison McComiskey, chair of the Environmental & Climate Sciences Department at Brookhaven National Laboratory. “Typically, wildfire season starts later in the summer and extends through the fall. If we’re going to be having wildfires of this size this early in the season and it continues, [there will be] much more of an impact on people in terms of air quality, health, and well being.”

Dry conditions caused by climate change intensified the severity of these fires, making them more difficult to extinguish and increasing the amount of particulates that can cause lung and other health problems thrown into the air.

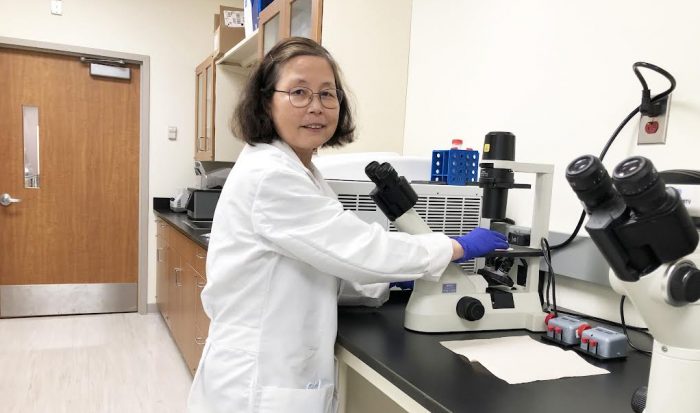

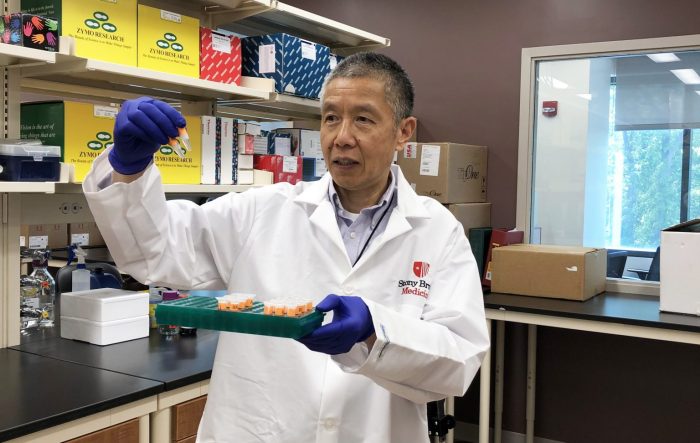

“Wildfire season is getting longer,” said Dr. Mahdieh Danesh Yazdi, an air pollution expert and environmental epidemiologist from Stony Brook’s University’s program in Public Health. These fires are “spread because we have drier conditions, the vegetation is dry, we have droughts. Those require long-term solutions of trying to tackle climate change on a fundamental level.”

The intensity of the smoke and the cancelation of events like the Yankees and Phillies games has raised awareness of the downwind dangers from wildfires.

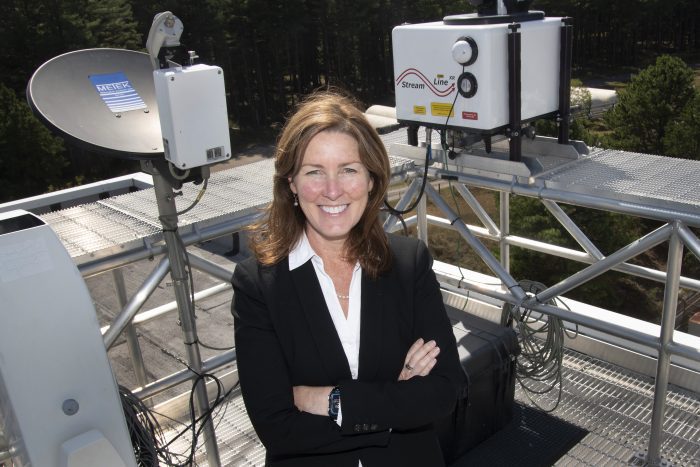

“This is like our Hurricane Sandy from an air quality perspective,” said Brian Colle, division head in Atmospheric Sciences at the School of Marine and Atmospheric Sciences at Stony Brook University.

Scientists urged a multi-level approach to tackle a wildfire problem that they believe will become increasingly dangerous for human health.

Forest management, including controlled burns, would reduce the available fuel for fires started by natural causes such as lightning.

“Forest management may be one approach,” said Dr. Danesh Yazdi. That alone, however, won’t solve the threat from wildfires amid higher temperatures and more frequent droughts, she added.

McComiskey added that researchers are “certain” that wildfires are going to increase in the future due to climate change and suggested that these events ratchet up the need for getting better predictive models about what these fires will mean for human health and the climate.

The heavy smoke that descended on New York, which some health officials described as creating conditions for those who spent hours outdoors that are akin to smoking several cigarettes, is “a wake up call that we need policies” to deal with the conditions that create these fires, McComiskey said.

The increase by a “fraction of a degree in temperature is really not the point,” McComiskey added. “We need to decarbonize our economy and we need to move toward addressing the bigger causes of climate change.”

A wildfire occurring earlier in the year with smoke filled with particulates could raise awareness and attention to the dangers from such events.

“Having this kind of thing happen in the East Coast through New York and [Washington] DC, as opposed to where we typically think of bad wildfire happening out west, in Washington State and the Rocky Mountains, might help in terms of the awareness and urgency to take some action,” McComiskey added.

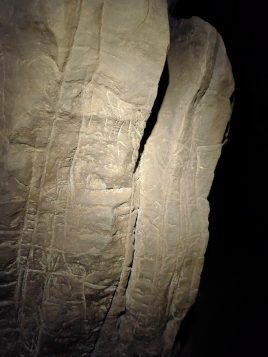

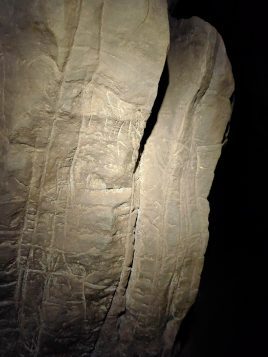

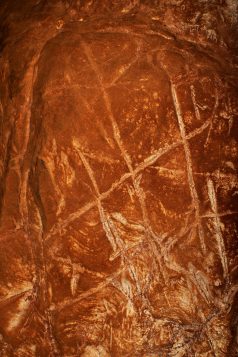

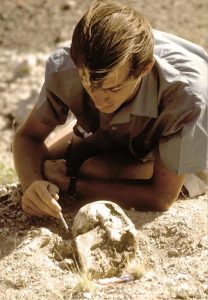

The University, which has 15 speakers among the 40 scientists delivering lectures, will celebrate the achievements of famed and late scientist and conservationist Richard Leakey and will bring together researchers from all over the world to celebrate the research in Africa that has revealed important information about early human history.

The University, which has 15 speakers among the 40 scientists delivering lectures, will celebrate the achievements of famed and late scientist and conservationist Richard Leakey and will bring together researchers from all over the world to celebrate the research in Africa that has revealed important information about early human history.