By William Stieglitz

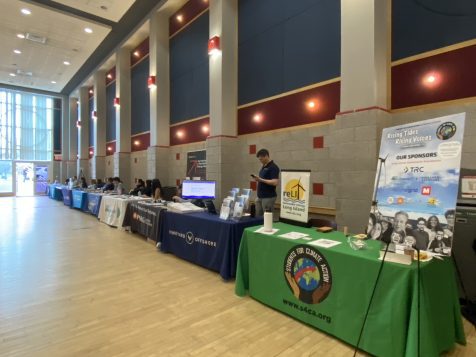

Approximately 300 students from 17 local high schools and at least one middle school gathered April 4 for the first Long Island Youth Climate Summit at Stony Brook University. Organized by Students for Climate Action and Renewable Energy Long Island, the event centered on environmental education and advocacy, with students encouraged to get involved with grassroots.

“It’s really important that students remember that they have a voice, that they have power, that there’s a lot they can do locally,” said Harrison Bench from S4CA. “We are teaching students about the science behind climate change, the science behind renewable energy, but we’re also giving them practical tools in advocacy. … They go back to their towns, their communities, their schools, and they have the actual skills necessary to continue to push for change, where change matters most.”

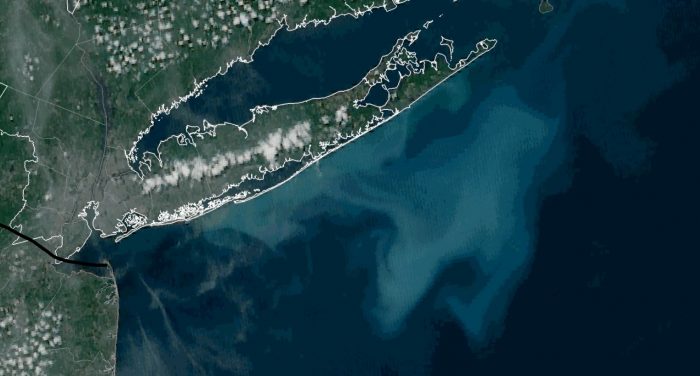

Speakers at the event came from a variety of organizations. Adrienne Esposito, executive director of Citizens Campaign for the Environment, taught how to distinguish misinformation from environmental fact. Energy and construction organizations, such as the Haugland Group and the New York State Energy Research and Development Authority, spoke on the benefits of offshore wind and solar projects, while also encouraging careers in climate and energy. And Monique Fitzgerald, a climate justice organizer at Long Island Progressive Coalition, shared information on New York’s 2019 Climate Act, which aims to lower greenhouse gas emissions but has not been fully funded, and encouraged calling on Governor Kathy Hochul (D) “to double down on investments in New York State.”

Additionally, there was a panel with six elected officials — Suffolk County Executive Ed Romaine (R), Suffolk County legislators Steven Englebright (D, Setauket) and Rebecca Sanin (D, Huntington Station), Southold Town Supervisor Al Krupski (D), East Hampton Town Deputy Supervisor Cate Rogers (D) and New York State Senator Monica Martinez (D/WF, Brentwood) — who all spoke on the importance of advancing clean energy. Bench expressed that he would have liked an even larger turnout of representatives, saying “it would have been really great to have more Republican elected officials on the town board,” but also that he hopes to increase the number for next year.

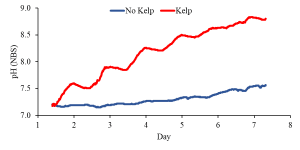

The student response to the event was positive, with the teens saying they especially appreciated learning about offshore wind and hearing from keynote speaker Christopher Gobler, from the School of Marine and Atmospheric Sciences at Stony Brook University. “I like that it brings attention to a lot of the issues right now,” said a student from Westhampton Beach High School. “It’s super, super important, especially in our political climate, with the pulling out of the Paris Climate Agreement.”

“I feel like it was very empowering,” said another student, who does local beach cleanup each summer. “Before, I thought that maybe I wouldn’t have had as much of a difference, like, just one person at a time. Now I’m hearing that there’s 300 other students here that are all here for the same reason. We can all go out together and all make an impact and that together, I feel like, [we] can really make a difference in the world, which is what I really care about the most.”

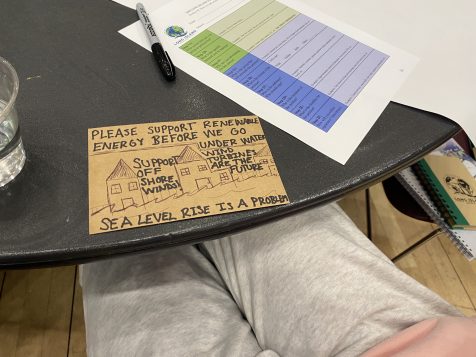

After about 4 hours of learning, students took a break for pizza and to meet with exhibitors from organizations such as PSEG Long Island, the New York League of Conservation Voters and Drive Electric Long Island. They then reconvened for action items, starting with making postcards to send to their congressional representatives. Students wrote letters on one side and got creative with designs on the other. Among the colorful images of wind turbines and the globe were messages such as “Only One Planet Earth,” “Use your brain power! Support wind power!” and “Please support renewable energy before we go under water.” Afterward, the students started petitions to bring back to their schools, focusing on crafting their asks, arguments, methods of distribution and timeline.

Melissa Parrot, executive director of ReLI, said the summit “exceeded our expectations.” She wanted the event to be solution oriented rather than just restating the problems. “We know we wanted climate science. We know we wanted action. We know we wanted careers. We know we wanted elected officials to be part of this process. So it kind of just figured itself out.”